|

I don’t know what it is, but I find that my eye is frequently drawn to the sight of a croft house sitting isolated in the landscape here on the Peninsula. It as if each one of these small and rather innocuous buildings has a story to tell and I guess this is why I find them so profoundly captivating. When it comes to a photograph of one, it is certainly true that a picture paints a thousand words. It’s almost as if the image is inviting me to immerse myself in a narrative that intertwines history, culture, nature, and human resilience. The narrative begins with their construction, in a time when the Scottish Highlands was sparsely populated, and life was dictated by the seasons. Back then they would have had sturdy stone walls with rounded corners to help combat the wind and treasured timbers would have supported a thatched roof. The use of locally sourced materials in these parts of the building standing as a testament to the craftsmanship and ingenuity of the crofters who had to live in harmony with their surroundings in order to survive. One can only imagine the challenges faced as the occupants practiced subsistence farming, growing crops like barley, oats and potatoes, and rearing a few cattle and sheep. However, despite the hardships, my sense is that the crofting way of life fostered a strong sense of community and mutual dependence, with the crofters working together during peak times, such as at harvest time and peat cutting. Indeed, the communal working and gatherings at important agricultural milestones would have provided opportunities for celebrating together. So, when I look at these houses, I can almost hear the murmur of voices and the echoes of laughter as the families shared stories and songs that passed from one generation to the next. The landscape surrounding the house is equally integral to its story. Whether it be rolling hillside, open moorland, sand dunes or rocky foreshore, a photograph of a croft house set against a vast and rugged landscape speaks to the symbiotic relationship between the crofters and their environment. It’s a story of respect for nature and one that changes with the seasons.

In spring, the landscape might be carpeted with blossoming wildflowers, symbolising renewal and hope. Summer’s light might cast a red glow across the walls and roof of the house, bringing a sense of warmth and security. Autumn introduces a palette of golds and oranges, a time of harvest and preparation for the winter ahead. Finally, in winter, the house, perhaps dusted with snow, stands as a beacon of warmth and safety amid the stark, cold landscape. Although stone built walls and thatched roofs have been replaced by white rendered walls and slate roofs to give us the croft houses we see today, these buildings still captivate my imagination and permeate a sense of history and heritage. To me, they are more than just structures; they are a living, breathing testament to the resilience of the people who have endured centuries of hardship and adversity to call this rugged landscape home. Such scenes speak to me and tell me a story not just of survival, but one of thriving in harmony with the land, drawing strength from the beauty and harshness of nature and this is perhaps why I find both my eye and my camera drawn to them.

0 Comments

I been looking through my library of images in recent weeks, looking for common themes that might form the basis of a couple of projects for the next 12 months or so and noticed that there were a few photographs that were taken during what is called the “Blue Hour”, an incredibly photogenic time of the day when the landscape is infused with rich, blue tones. One of these images is below and it shows Ardnamurchan Lighthouse on its rocky promontory with the sea, the land and the sky all tinged with these rich, blue tones. So what exactly is the blue hour? The blue hour occurs twice a day, just before sunrise and just after sunset, so you might be thinking that it is simply the time of day known as twilight, but there is a little more to it than that. This first thing to know is that there are three phases of twilight: civil twilight, when the Sun is between 0° and -6° below the horizon; nautical twilight, when it is between -6° and -12° below; and astronomical twilight, when it is between -12° and -18°below. During civil twilight, there is still colour in the sky, and it is light enough to see objects clearly; the sky is darker during nautical twilight and by astronomical twilight it's almost completely dark. The evening blue hour is the period of transition from civil to nautical twilight (or vice versa in the morning), when the Sun is between -4° and -8° below the horizon. At this time, the longer red wavelengths of light from the Sun pass straight out into space and the shorter, blue wavelengths are scattered in the atmosphere. The result is a rich and saturated cool blue colour that is incredibly atmospheric, so if romance and mystery are your thing, this really is a great time head out with your camera. Before you do though, you should know that despite its name, the blue hour only lasts for 20-40 minutes depending on your location, the time of year and atmospheric conditions. At this time of year here on the Peninsula, it begins at about 20 minutes after sunset and at 45 minutes before sunrise. In either case it lasts for around 20 minutes, so the opportunity for photography is fleeting, but nonetheless very rewarding. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, I find the blue hour to be an incredibly tranquil and thought-provoking time of day, and this is especially true of the evening blue hour. I’m not sure what it is, but this “in-between time” during which day transitions into night, I feel compelled to pause and appreciate the beauty of that exact moment. This is especially true if I’m out in the landscape alone with my camera because moments of such solitude bring a real sense of peace and stillness that allow me to disconnect from any stresses or challenges that I may have experienced during the day.

As the blue hour comes to an end, the sky transforms from the canvas of rich blues that I was photographing to a deepening shade of indigo. With this comes the gradual unveiling of the stars, with each one sparkling ever brighter as the sky darkens. As more and more stars become visible, I am often struck by the vastness of the cosmos and with this comes strong feelings of awe and humility due to Earth’s true insignificance. The sheer scale of the Universe, with its billions of galaxies each containing billions of stars, puts into perspective the minuscule size and fleeting existence of our home planet. It is a mere speck of dust in the cosmic ocean and seems so inconsequential in comparison to the unimaginable expanses of space stretching out in all directions. It is in these moments that I am reminded of the transient nature of human existence. Yet, amidst this feeling of smallness, there is also a sense of wonder and curiosity. The very fact that we can contemplate our place in the Universe, that we can marvel at the stars and ponder the mysteries of existence, is a testament to the extraordinary capabilities of the human mind. It is in moments like this that I just love catching the blues. I took the image below on a late February afternoon from the sandy beach at Port na Carraidh at the western end of the Ardnamurchan Peninsula. Like many of my landscape images, the process involved finding the composition, framing the shot and then a significant period of time waiting for the light to be right. While some people may find such time boring and perhaps frustrating, I find it to be one of the most enjoyable parts of the whole process because it provides an opportunity for some quiet reflection and thinking which, on this occasion, had me pondering the difference between knowledge and wisdom. I guess I ended up thinking about the difference between the two because photography, as both an art form and a technical skill, involves a delicate balance between knowledge and wisdom. Indeed, a photographer’s ability to capture compelling images is influenced not only by technical know-how but also by the nuanced application of wisdom.

Knowledge in its fundamental form is gained by the acquisition of information, facts, and skills which, in the case of photography, encompasses an understanding of things such as camera settings, composition rules, lighting techniques, and post-processing tools. It is the photographer's proficiency in handling equipment, choosing the right exposure, and manipulating elements within the frame that provides the necessary foundation for capturing technically sound images. In contrast, wisdom goes beyond the mere possession of such information and the technicalities of taking a photograph. It allows photographers to determine the relevance of various pieces of the information that make up their knowledge and how best to apply it to their own work. To my mind, a wise photographer understands that a compelling image is not solely about pixel-perfect technical execution but about conveying a story, evoking emotions or capturing the essence of a moment. One key distinction between the two lies in how they are acquired. Knowledge can be obtained through formal education, reading and observation. It is quantifiable and can be measured in terms of proficiency in a specific field or the retention of factual details. I’m sure everyone will remember dreaded exams at school that aimed to do just this. Wisdom, on the other hand, is cultivated over time and often matures through a combination of life experiences and introspection, and a willingness to learn from both successes and failures. It certainly can’t be measured in a way that knowledge can be. When thinking about the image above, my sense is that wisdom encouraged me to make thoughtful decisions about what to include in the frame and what to exclude from it, it helped me recognise the emotional impact of light and encouraged me to wait the time I did to take the photograph. The result was that I pressed the shutter button just when the conditions were right and created an image that conveyed the emotions that I wanted it to. In my photographic journey, like many people I guess, I began it by acquiring knowledge through learning the basics of composition, exposure, and editing techniques. It was only after I understood these basics that I was able to practice, try photography under different conditions and, probably most importantly of all, learn from my successes and failures. Recently, I have been reviewing images that I took a few years ago, and comparing those that invoke some form of emotional response with those that don’t. By doing this, I’m working on identifying recurring themes, styles, and subjects that resonate with me. My hope is that by incorporating these elements into my future work, I can refine my artistic style and more consistently create images that resonate deeply with not only myself, but also audiences that view them. Although Ben Nevis sits just to the east of Fort William, its height of 1,345 metres (4,413 feet) not only makes it the highest mountain in the British Isles, but also means that it is visible from a number of places on the Peninsula. One such place is Lochan Doire a' Bhraghaid and this is where I took the photograph below. It was taken on a cold January morning when the pink light from the Sun rising in the south-east was caught by the mountain’s south facing upper slopes and the clouds that covered what is an extremely elusive summit. A summit that, perhaps one day, I’ll be lucky enough to capture. The summit of Ben Nevis is notorious for unpredictable and often harsh weather conditions that are constantly influenced by North Atlantic weather systems. The mountain is in an area that experiences a significant amount of precipitation, averaging around 4,406 mm of rain annually. This, combined with the mountain's height, creates a perfect environment for cloud formation. The warm and moist air from the Atlantic meets its high peaks, resulting in the frequent presence of clouds. In fact, its summit is only visible for an average of 30 days per year, making it extremely elusive and therefore a challenge to photograph. However, I am hoping that with a little planning, patience, and persistence, I will eventually get the shot that I have in my mind’s eye.

Planning is the cornerstone of successful landscape photography and involves thorough research and preparation before heading out to a location. In this instance, the factors to consider are weather conditions, time of day, and the position of the sun. For the shot I’m after, I’m looking for an unobscured snow-covered summit with warm sunlight falling on the sides of Ben Nevis that are visible from Lochan Doire a' Bhraghaid some 17 miles to its southwest. This means that the shot needs to be taken on a morning during a cold and clear spell of weather in the months of December, January and potentially February because this is when the sun will be rising in the right place. I used various topographic maps and sun tracking apps to help me pick these months and various weather forecasts help me decide which days to go out on. Next up is patience. Nature does not always cooperate, and capturing the perfect shot often requires waiting for the right moment. The ideal lighting, weather conditions, and natural elements may not align immediately so I often find myself waiting an hour or more before I feel that the time is right to press the shutter button. On the morning I took the image above, I arrived before sunrise to see that the summit of Ben Nevis was clear. I therefore set up my tripod, framed the shot and waited in anticipation of Sun rising to bath it in a warm pink glow. However, it was not to be because a bank of cloud rolled in from the north and obscured the summit just as sunlight began to fall on the mountain. So finally, this is where persistence comes in, because it involves a commitment to returning to a location time and time again until the conditions are just right. In this instance, the lighting may have been perfect, but the weather did not cooperate. It was tantalisingly close, but that 1 in 12 chance of the summit being clear conspired against me and I didn’t quite get the shot I was looking for. In fact, I have returned to Lochan Doire a' Bhraghaid a few times since to capture that “elusive peak”, only to be met with no success. Never mind though. The thrill of landscape photography is often to do with the “chase” and when the conditions eventually do align, the resulting image will be more than enough reward for all the planning, patience, and persistence. Until then, I look forward to the day when I can share the image that I have in my mind’s eye with you. In today’s world of smartphones and digital cameras, photography has become more accessible than ever before, and we see social media full of images of places and events that people have chosen to share. It is fantastic that people can capture these images with a simple click of a button, but this act of taking a picture is quite different from the art of making a picture. It’s something I’m very aware of when making images such as the one below, which shows one of the most spectacular sunsets I’ve ever seen out at Ardtoe. This is because, in such moments, I’m not only trying to capture what my eyes saw, but also what my heart felt. For me, taking a picture refers to the act of quickly capturing a moment, scene, or subject without much thought or consideration. It can be spontaneous, casual, and primarily focused on preserving memories or documenting an event. The emphasis is on the subject itself rather than the photographer's creative interpretation. In this sense, taking a picture is often associated with casual photography, such as snapshots, selfies, or everyday moments captured on the go.

On the other hand, making a picture is a deliberate and intentional process in which the photographer uses their technical and creative skills to transform a scene or subject into a visually compelling image. The focus shifts from simply recording what is in front of the camera to crafting an image that conveys a specific message and evokes certain emotions. When taking a picture, you typically rely on the automatic settings of a camera or smartphone, allowing the device to make decisions about technical aspects such as exposure and focus. The priority is to capture the moment quickly and efficiently. In contrast, making a picture often involves a more involved manual approach, where you take control of the camera settings to achieve a desired aesthetic. In landscape photography, this typically involves selecting the right lens and focal length; adjusting the aperture, shutter speed and ISO; and reading the weather and light conditions to determine the best place and time to press the shutter button. Taking the image above as an example, I planned and made repeated visits to a particular spot at Ardtoe at this time of the year because I knew that I would see the Sun setting behind the Isle of Eigg from there. The specific days on which I made these visits were determined by the weather conditions, with me looking for low cloud directly overhead and gaps in the clouds on the western horizon through which light from the setting Sun would shine. I chose a lens with a long focal length, that would bring the distinctive silhouette of An Sgùrr on Eigg closer to the skerry of Sgeir an Eidigh. I set the aperture so that both would be in focus because they were key elements of the story. I set the ISO and shutter speed to let the correct amount of light into the camera when using a long exposure time to smooth out the sea so that it would not detract from these key elements. Finally, I waited with great anticipation for the rays of light to break through the clouds and light up An Sgùrr to create the perfect moment to press the shutter button. It was only then that I was able to make the image that I had in my mind’s eye. A simple but distinctive image that conveyed the dramatic beauty of a mid-summer sunset that featured the unmistakeable profile of An Sgùrr on the Isle of Eigg. So, although both picture taking and picture making have their place in photography, it’s the latter that I find the most satisfying. You have to be prepared for disappointments and failures along the way, but with planning, patience, and persistence, you will be rewarded with images that go beyond mere documentation to capture and evoke the emotions you felt at the precise moment you pressed the shutter button. I wonder how often folk have driven past the Ardgour War Memorial and never paid it much attention. This was certainly the case for me, having passed it countless times on my way to and from the Corran Ferry, until one day when I found myself with some spare time at the marshalling area on the Ardgour side of the Corran Narrows. After deciding to go for a quick walk, I found myself up on a bank just south of the lighthouse, standing beside the War Memorial and looking southwards at an expansive view of Loch Linnhe. While standing there, I spotted something that I would later learn played a small part in a huge project that is thought to have been key in bringing World War I to an end. The Ardgour War Memorial is typical of the many that you find scattered across the Highlands, consisting of a granite Celtic cross and plinth mounted on a base of what seems to be made of local stone. Whilst here, I took a moment to stand by it with my eye drawn to the wreath of red poppies that had been laid at the base of the cross and to the words inscribed on the plinth beneath it: IN MEMORIAM PARISH OF ARDGOUR THE GREAT WAR 1914-18 _____ DO'N GHINEALACH A RINN ÌOBAIRT SADH FHUILING CRUADAL, S A SHEALBHAICH BUAIDH _____ TO THE GENERATION WHICH BORE THE SACRIFICES AND BY SHARING IN THE HARDSHIPS, ACHIEVED VICTORY I then noticed that the Memorial’s stone base was sitting on what appeared to be a metal ring with several bolts protruding from it. I didn’t give them much thought at the time, but a day or two later, I couldn’t help wondering what they had been used for, so decided to try and found out.

The mines were being used in the North Sea Mine Barrage, a large minefield laid easterly from the Orkney Islands, right across the top of the North Sea to Norway with the aim of preventing the U-Boats based in Germany from making their way out into the Atlantic to attack the convoys that were bringing supplies from the United States to the British Isles.

I took these words for the image title from the seventh stanza of the poem, “For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon, which reads:

“As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust, Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain, As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness, To the end, to the end, they remain.” The poem is more commonly known for its third and fourth stanzas as they are often recited at Remembrance Day services as what is termed the "Ode of Remembrance", ending with the familiar words “We will remember them”. Despite the words of these two stanzas being extremely thought provoking, I find the words of the seventh stanza incredibly moving because there is such strong sense of poignancy to them. I guess that’s why I used them as the title for this image. The image below shows Ardnamurchan Lighthouse shortly after Storm Eunice had swept across the southern part of the UK leaving a £360m trail of disruption in its wake. Thankfully, the Peninsula missed the worst of the storm, experiencing only moderate gale force winds and not the hurricane force winds that swept across the south of the UK. However, considering that the names of the 6 deadliest storms from UK history are called the 1607 Bristol Channel Flood, the Great Storm of 1703, the Eyemouth Black Friday Storm of 1881, the Blizzard of 1891, the North Sea Flood of 1953, and the Great Storm of 1987, I was left wondering why one of the most powerful storms to hit the south coast of England was simply called Eunice. Well, a little bit of research found that there is a lot of power in such a simple and innocuous name In 2015, the UK Met Office and its Irish counterpart Met Éireann launched the "Name Our Storms" campaign to raise public awareness of severe weather and to create a single naming system that could be used to aid the communication of approaching severe weather. The result was a list of names that could be used for the 2015/16 storm season, running from early September of 2015 to late August 2016, with further such lists for every year since then. This campaign proved to be particularly effective at gaining attention on social media and reaching groups of people that had previously been difficult to engage with, meaning that in general, the public became better placed to keep themselves, their property, and businesses safe during major storm events. Such was its success, that the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) joined the initiative in 2019, recognising that it made a lot of sense to give common names to such extreme weather events. So now, from around June each year, members of the public from all three participating countries are asked to suggest names for the coming storm season so that a list of selected names can be published on the first day of September. The list is made up of alternating male and female names for each letter of the alphabet, except for Q, U, X, Y and Z. The reason these letters are not used is that there are not many names that begin with them. Going back to 2015, the first ever name was used to name Storm Abigail, a storm that brought strong winds and heavy rain to much of the UK on 12-13 November 2015, with the most severe weather impacting the northwest of Scotland where power cuts affected up to 20,000 homes and many schools were forced to close for the day. Returning to this year, the first name for this current storm season was selected by KNMI. It is Antoni and along with Hendrika, Johanna and Loes, is named after an influential Dutch scientist. Met Éireann’s submissions include Cillian, Fleur, Íde, and Nelly and the Met Office’s names include Betty, Daisy, Glen, Khalid and Owain and show the breadth of names in use across the UK. In fact, Betty became the runaway winner of a public vote on Met Office Twitter, with over 12,000 votes cast to select it as the name for the letter B. Storms are named once they have the potential to cause medium (Amber) or high (Red) impacts to the UK, Ireland or the Netherlands with the effects of wind, rain and snow all being considered when deciding if a name should be used and this season things appear to have been relatively benign because it is mid-February and Antoni is yet to be used to name a storm.

This contrasts with last season when the first storm, Storm Arwen brought destructive winds rain and snow to the UK in late November. It was named on 25 November 2021 and on 26 November 2021, the UK Met Office issued what they described as a "rare red weather warning" due to a deep pressure system moving southwards from the Atlantic Ocean. When the system made landfall in Aberdeenshire, it brought extreme wind and waves all the way down the coast from there to the Tees Estuary. By the time the Storm Arwen had passed it had left more than a quarter of a million customers without electricity and three people dead. The damage it caused was compounded by sustained winds with gusts in excess of 90 mph that came unusually from the north-east and toppled around 16 million trees, the vast majority of which would have survived had the winds been from the prevailing south-west wind direction. Storms Barra and Corrie followed in December and January and then, between 16 and 21 February 2022, the UK was successively hit by storms Dudley, Eunice, and Franklin. Of these, Eunice was the most severe with South Wales and the southwest of England being worst hit. On 17 and 18 February 2022, the Met Office issued to two rare red warnings for much of southern England, south Wales and London effectively telling about a third of the UK population to stay at home. Eunice was one of the most powerful storms to impact the south coast of England since the Great Storm of 1987 and at its peak on 18 February, record gusts of 122 miles per hour were measured at the Needles on the Isle of Wight. By the time Eunice had passed, 4 people had sadly died as a result of it, over a million homes were left without power, a huge hole had been torn into the roof of London’s O2 Arena, a church spire in Wells, Somerset had been blown down, hundreds of train services and flights were cancelled, and many major roads were closed. The estimated bill for all the damage and disruption caused was £360 million. However, the Met Office said that things could have been a lot worse had it not been for the storm naming system ensuring that better messaging had been in place than that for the Great Storm of 1987. This meant that people had been more aware of Storm Eunice approaching, better prepared for it arriving and had heeded the warnings not to travel. This certainly shows that we should never underestimate the power of a name and simple messaging. I would never have thought that a seemingly innocuous slip on a wet rock at Ardtoe would have resulted in a debilitating injury requiring surgery, 4 months of immobilisation, 12 months of physiotherapy and a further 6-12 months of recovery time to get me back to a point where I can freely walk in and photograph the landscape here on the Peninsula. However, this was indeed the case, and I am thankful that I had my photography to use as the motivator to get active and aid my recovery. It also resulted in the creation of a collection of 72 images that portray the varying landscape and moods of the Peninsula throughout 2022. This blog contains 12 of these images, one for each month of the year, and I hope to share the remainder of them over the course of 2023. The BackstoryOn 6th July 2021, I slipped on some wet rocks at Ardtoe, dislocating my knee and tearing my patellar tendon in two. Following an operation to repair the damage, I found myself immobilised and in a knee brace until early November and unable to get out and do any photography. While laid up in the brace, I set myself the target of getting back out with the camera by the start of 2022 and the objective of taking 5 or 6 images each month that captured the varying landscape and moods of the Peninsula throughout the year. With limited mobility, especially at the start of the year, I had to think carefully about locations I could safely go that would provide me with opportunities to take the photographs that I had in mind. This was a bit of a challenge at first, but I found that this limitation helped me with my creativity. By the end of the year, I had visited enough locations and taken enough photographs to enable me to create a collection of 72 images, or six for each month to reasonably portray the Peninsula over the course of 2022. Twelve of these images, one for each month, are presented in this blog and I plan to share the rest of them over the course of the coming year in a new section on this website titled “A Year on the Peninsula”. As well as the collection of images, the project provided me with the motivation to get “out there” and get back into my photography and aid my recovery. When pulling these images together, I was certainly reminded of how far I have come since that day in January when I gingerly made my way down the jetty at Salen with the help of a crutch to take the first photograph in this collection. I still have a number of months left in my 18-24 month long recovery period and hopefully, as my ability to walk on uneven ground and also downhill improves, I’ll be able to range further afield and photograph locations that I have not been able to get to since that fateful day in July 2021. The ImagesAnticipation I - Loch Sunart, Salen Jetty, Ardnamurchan

I started the year with some early morning visits to the old jetty in Salen because in January, the sun rises well round to the south-east and is able to cast beautiful light and colours onto the waters of the bay and the jetty itself. On my final morning, the sun seemed to take an age to appear from behind the hills of Morvern, but it was well worth the wait. Distant Lighthouse I - Port na Carraidh, Ardnamurchan

Mid-February brought Storm Eunice along with its record-breaking winds and widespread disruption. The day after the Storm had passed, I headed out to Port na Carraidh at the western end of the Peninsula with the aim of photographing a distant view of the Lighthouse and after much searching I settled on this composition that used the stream on the sandy beach to lead the eye out to it. Tioram and the Zodiac - Castle Tioram, Dorlin, Moidart

In March, the Zodiac rises steeply from the horizon at dusk, making it a great time for spotting Zodiacal Light. Caused by light from the sun reflecting off a fog of tiny interplanetary dust particles that fill our inner Solar System, it shows as a faint triangular glow rising steeply from the western horizon just like in this image I took at Castle Tioram. Light on Risga - Loch Sunart, Glenborrodale, Ardnamurchan

This shot was taken on an April morning when I was driving back home from an overnight photo session out west. As I approached Glenborrodale, the first light of the day was falling on the island of Risga, the skerries around it and Carna behind it. A sight that was simply too beautiful to not stop and photograph. Caisteal nan Con I - Bagh Caisteal, Killundine, Morvern

Caisteal nan Con (Castle of Dogs), overlooks the Sound of Mull on the eastern coast of Morvern. I have passed it a few times on trips out to Drimnin and it has always caught my eye, so I decided to stop when passing it late on an evening in May and photograph just as cloud was rolling in from the west and catching the pinks from a setting sun. Day's End, Land's End - Ardnamurchan Lighthouse, Ardnamurchan

Three days after the longest day of the year, in late June, I was out at the lighthouse for its 25th anniversary of community ownership. The day had started with wind and rain but the afternoon cleared and I decided to capture the day’s end a good few hours after the anniversary celebrations ended. The sun set in the northwest shortly after 10:00 pm. Sundown Blues II - Sailean Dubh, Ardtoe, Ardnamurchan

A “must do” thing to do in July is to watch the sun set directly behind the Small Isles of Eigg and Rùm from the headland on the western side of the beach at Ardtoe. I had spent a very peaceful time doing just that in the couple of hours before I took this image of the blues of the emerging blue hour mixing with the golds of sunset. Return of the Stars - The House Pool, River Shiel, Blain, Moidart

In August, the lengthening nights mean the return of stars and up until early October, you can marvel at the sight of the Milky Way filling the sky with a cloudy band of stars. This image shows it soaring above the House Pool on the River Shiel on a night in late August when I must have seen around a dozen shooting stars from the Perseid meteor shower. Harvest Moon Reflections - Ardtoe Pier, Kentra Bay, Ardnamurchan

In September, the full Moon rises in the southeast and if you watch it from Ardtoe Pier at the western end of Kentra Bay, it will appear above a distant Ben Resipole and cast reflections onto the water in the bay as it does so. In 2022, it was the nearest full Moon to the autumnal equinox, earning it the title of 'Harvest Moon'. Lilac Dawn - Loch a' Choire, Kingairloch, Ardgour

Loch a’ Choire is at the heart of Kingairloch Estate and in October the Sun rises in line with its east facing entrance and can create some beautifully vibrant sunrises there. I had hoped to capture one of these sunrises on the morning I was there, but haze and cloud on the horizon subdued it and instead created some lovely lilac hues on the loch’s surface and in the sky above it. Two Bridges - River Shiel, Blain, Moidart

The 2.5-mile-long River Shiel flows from Loch Shiel to the sea and forms part of the boundary between Moidart and Ardnamurchan. It can be crossed by either of the two bridges shown in this image which was taken on a November afternoon when the light bathed the autumn-coloured trees on the Moidart side it. Ben Resipole can be seen in the distance. A Year Ends - Kentra Bay, Gobshealach, Ardnamurchan

Early December brought clear blue skies and sub-zero temperatures which were followed by two weeks of milder weather, wind and heavy rain. Fortunately, this broke for a little while on New Year’s Eve to allow me to capture dusk falling on the mouth of Kentra Bay as the end of the year approached. The Small Isles of Muck, Eigg and Rùm are in the orange glow on the horizon. With its ever-changing weather, dramatic landscapes, beautiful lochs and ancient woodlands, the Peninsula often seems to be a magical and mystical place to me and like much of Scotland, legendary stories used to explain the unexplainable and to warn us away from dangerous places, have been carried down through the generations. Indeed, photographing the Peninsula often leads me to uncovering links between legends and its landscape, just as it did when I photographed Loch Sunart one November day. The image above was captured from the upper slopes of Meall Mor, a small peak that sits on the western flank of Ben Resipole. I have been up there many times because it is only a short distance from my house and the modest climb is rewarded with stunning views westwards over Loch Sunart to the Isle of Carna and the hills of Morvern beyond. While taking this photograph, I saw something that I hadn’t noticed before. A small promontory sitting in front of the silhouette of the Isle of Carna, which only caught my eye because it was lit up by rays of light that had broken through the clouds. Curious as to what it was, I did a bit of research when I returned home to find out that this knoll was both the site of a small Iron Age fort called Dùn Ghallain (Fort of the Storm) and the setting of ‘The Swan of Salen’, a mythical tale that seeks to explain why no swans are found on Loch Sunart. It tells of a Chieftain who fell in love with a maiden of low social status. The Chieftain’s mother disapproved of the match and turned the maiden into a swan. The Chieftain, not knowing this, killed the swan while out hunting and was heartbroken to see the swan’s body take the form of his love as it died. Inconsolable, he fell on his own sword, and the bodies of the two are said to lie beneath Dùn Ghallain to this day. It is said that this is why there are no swans on Loch Sunart, making it the perfect example of a tale to explain the unexplainable. If you travel a few miles east from there, you can find a location whose name is linked to a legend that warns you away from danger. It is Lochan nan Dunaich, the ‘Little Loch of Sadness’, where young children were supposedly lured into its waters by a Kelpie and never seen again. Kelpies are said to be water spirits that inhabit many of the rivers and lochs of Scotland. Although usually appearing in the form of a horse, they are capable of shape-shifting and can take human-form. When in horse form a kelpie will often stand near the edge of a river or loch waiting for its prey, which will often be young children. Kelpies have magically adhesive bodies, meaning that should a child choose to clap the supposed horse, they will become attached, allowing the Kelpie to drag its victim into the water and drown them.

It is also said that they can stretch the length of their backs to carry several children to their death at once. One tale involves a group of children, where all but one climbed onto the kelpie’s back while the last child stayed on the shore. This child petted the kelpie’s neck only to have their hand become attached to it. They freed themselves by cutting off the hand only to then watch their friends, who were stuck to the kelpie’s back, being dragged down into the depths of the water where they were devoured, and their entrails thrown to the water’s edge. When you look at Lochan nan Dunaich, a deep and dark pool of water with fallen trees around its boggy edges, you can well understand the need to warn children away from straying too close to it and with such gruesome tales about Kelpies, you can well understand how the local legend would have been to this effect. So, if you find yourself there, tread carefully, very carefully indeed. When you hear someone say, "Once in a blue moon …" you probably think that they are talking about something rare. In fact, this month’s image shows the blue moon of October 2020 sitting above the summit of Càrn na Nathrach in Ardgour, with the peaks of Druim Garbh, Sgùrr Dhomhnuill and Sgùrr na h-Ighinn to its left. So, what exactly is a blue moon and is it actually that rare? Most people will have watched a white coloured moon traversing the night sky and some people may have even seen a yellow or red moon at moonrise or moonset. On the other hand, very few people will have seen a blue coloured moon because it is a very rare occurrence indeed.

This rare event, when the Moon can naturally appear blue, is caused by the presence of dust particles in the atmosphere which, if they are the right size, can scatter the red part of the light spectrum and leave the rest untouched to cause the moon to take on a blue tint. Some of the events that have led to this include the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 and the eruptions of Mount St. Helens in 1980 and the El Chichón volcano in Mexico in 1983. In fact, the eruption of Krakatoa reportedly caused blue moons for nearly 2 years. However, the bluish tint caused by these rare events doesn’t have anything to do with the phrase “once in a blue moon”. Instead, the words ‘blue moon’ are used to describe the second full moon in a calendar month. It is an event that is not that rare because there are 29.5 days between full moons, meaning that each year will have roughly 12.3 full moons. This gives us a 13th full moon once every 2.7 years, along with a month within which a second full moon, or blue moon occurs. In fact, the last blue moon to occur was the one that is shown in the image above, which I photographed in October 2020. The next one is in August 2023 and the one after that will be in May 2026. Considerably rarer than blue moons are double blue moons. This is when there are two blue moons in the same calendar year, and it is something that occurs about 3-5 times every hundred years of so. The last one was in 2018, the next is expected in 2037 and the one after that in 2067. Rarer still is what is termed a super blood blue moon. This is when a blue moon occurs when the Moon comes within 90% of its closest distance to Earth to make it a supermoon, while at the same time fully slipping into the Earth’s shadow to create a total lunar eclipse. This last happened in January 2018, just over 150 years since all three phenomena last lined up in March 1866. If you look at the frequency at which these three phenomena are expected to occur;

meaning that a super blood blue moon will occur 0.042% of the time, or once every 2,381 full moons. On average, that corresponds to once every 194 years! So, the next time you think about using the phrase “once in a blue moon” for something that almost never happens, you might want to consider using “once in a super blood blue moon” as an alternative!! We are now in August, the best month of the year for looking at and photographing the cloudy core of the Milky Way, the galaxy that is home to our Sun and 200 billion other stars. I find photographing this vast cloud of other stars and worlds an extremely humbling experience, especially when you consider that this single galaxy may contain 300 million potentially habitable planets and that there are a total of 170 billion other galaxies in the Universe as a whole. With mind-blowing numbers like these, we surely must consider the possibility of there being life beyond Earth. At this time of the year, the sun sets at around 9:00 pm and the stars and the constellations become visible from about 10:00 pm onwards. So, if you spend some time outside around then and look south, you’ll see the core of the Milky Way beginning to appear in the lower part of the sky. Having risen above the horizon in the southeast at about 7:00 pm, this cloudy mass of dust and stars will have travelled upwards and westwards to become visible as twilight ends. At this point, it reaches its highest point in the night sky and begins to drop down towards the horizon while it continues westward. It will eventually set around midnight, giving a period of about two hours during which it can photographed in all its glory. I was pleased to be able to do this when I captured the image below on a beautifully still and clear night from the Ardtoe Jetty in Kentra Bay.

With each of these 170 billion galaxies containing an average of 200 billion stars, and with the current consensus among astronomers being that there should be at least as many planets as there are stars, it can be estimated that there are at least 34 sextillion (34,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) planets in the universe.

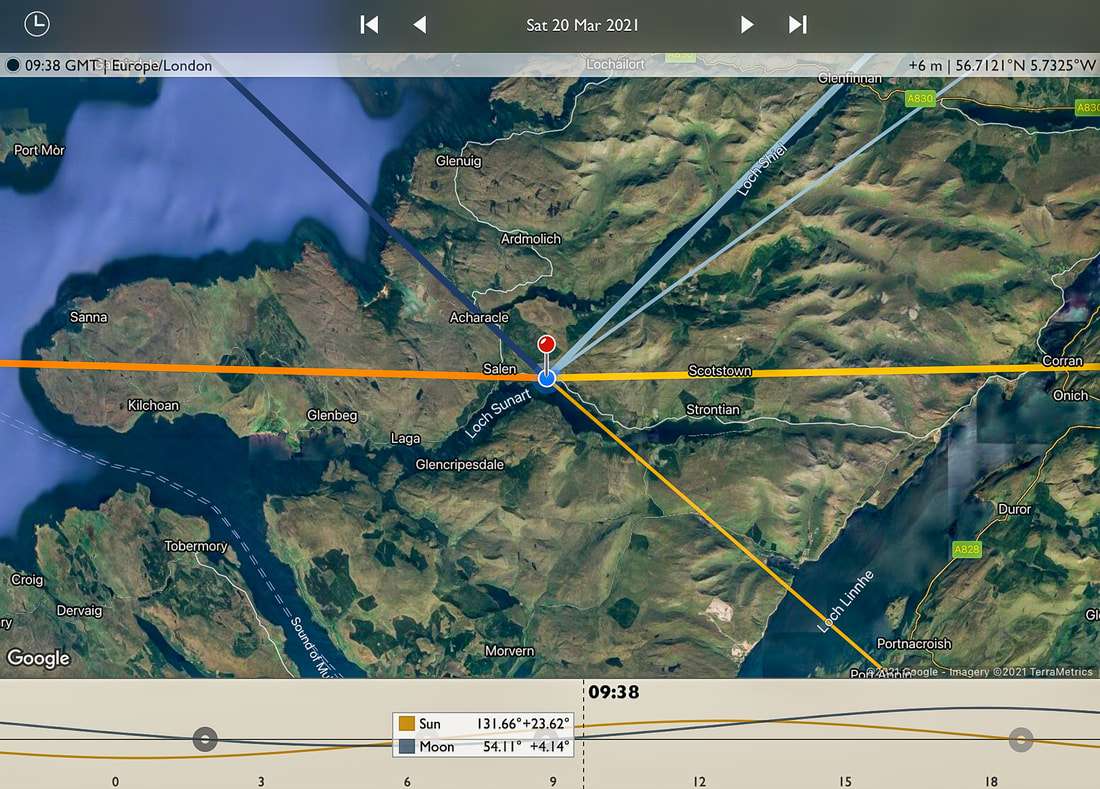

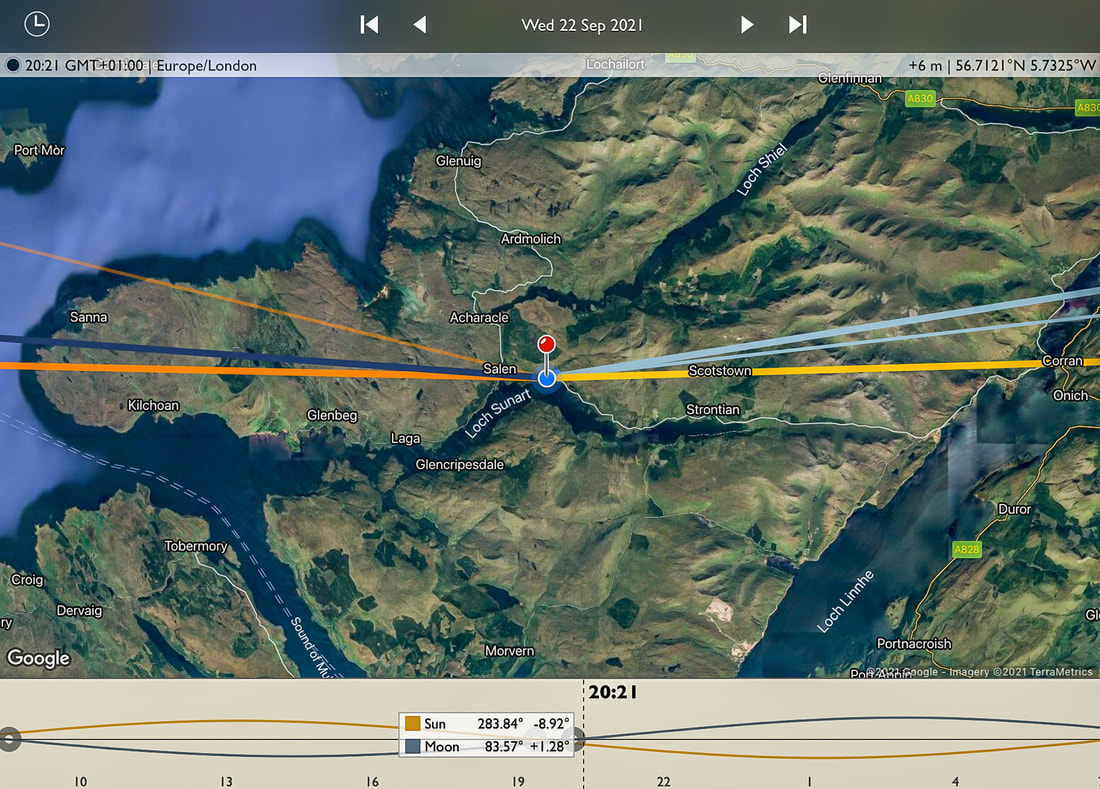

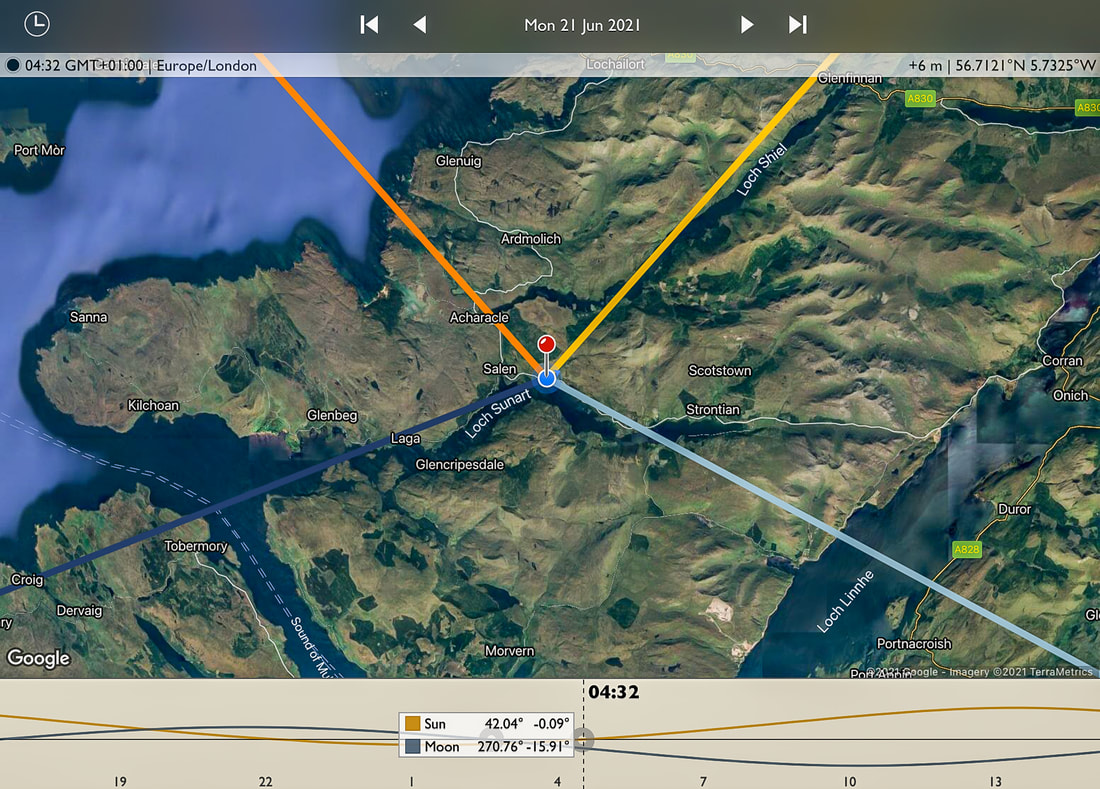

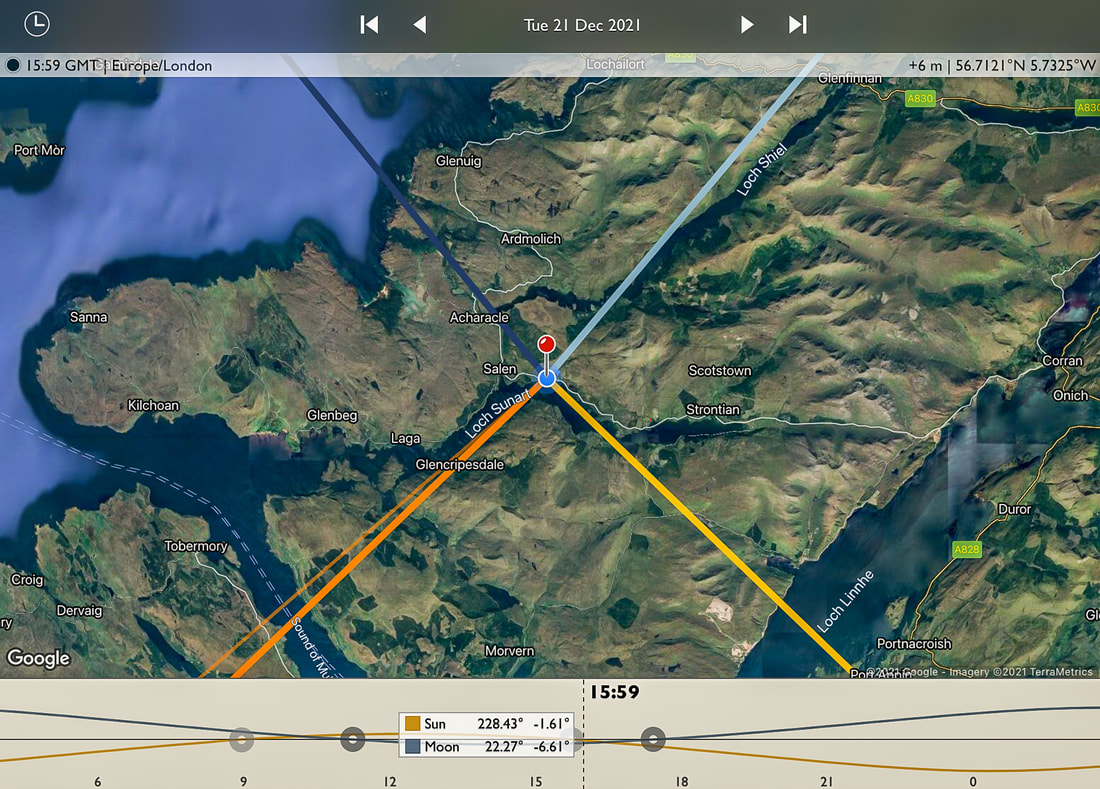

This is an incomprehensibly large number of planets, and it does make you wonder if there is indeed life out there beyond Earth. Indeed, to date, astronomers have found 55 planets that are orbiting the habitable zones of stars and by extrapolating this to the number of stars in the Milky Way they estimate that there could be 300 million such planets in our galaxy alone. So, with this in mind, why don’t you go outside after dark on a clear August night and look south to see the cloudy core of the Milky Way, consider that someone may be looking back at you and remember this quote by Carl Sagan, the renowned astronomer and astrophysicist: “The universe is a pretty big place. If it's just us, seems like an awful waste of space.” Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or on the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and is when day and night are of equal length and when the Sun rises due east and sets due west. Although this means that the dark nights return, it does mark the beginning of the beautiful sunsets over Loch Sunart that we get here at Resipole during the autumn and winter months and also increased chances of seeing the Aurora Borealis. Most people know that the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but they may not realise that this is quite a generalisation. In fact, the Sun only rises due east and only sets due west on two days of the year; the days of the Spring Equinox and the Autumnal Equinox which, for 2021, are March 20 and September 22. To illustrate this, Figures 1 and 2 show the location of the rising and setting sun at the Spring Equinox and Autumnal Equinox, respectively. Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Image 1, at the top of this blog, was taken at Resipole during sunset on the day after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, with the camera facing southwest down Loch Sunart towards the Isle of Carna and the hills of Morvern. If you look closely, you can see a patch of intense colour behind the wooded hillside on the right-hand side of the image. This was the spot where the sun was setting due west and for me, such a sight is one of the most welcome of the year because it marks the return of spectacular sunsets to this part of the Loch. With the passing of the autumn months and the movement of the setting sun towards the south, these sunsets become more and more intense. They are something that I’ll never tire of photographing even though I have taken countless photos of them from this spot. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen the same mix of colours twice. Each sunset is different because of the varying position of the sun and the infinite range of possible cloud formations that reflect the light from the sun and produce the kaleidoscope of colours. The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Image 2 above was taken 4 days after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, when I had a client out with me for some night photography tuition. We had spent the first part of the night preparing for and taking photographs of the Milky Way rising above Loch Sunart and while we were doing this a very high Aurora Alert came through on my phone. We quickly packed up our camera gear and headed up to Acharacle and set it up again on the jetty there is on Loch Shiel. It is a perfect spot to look for and photograph the Aurora Borealis because it faces directly towards northern horizon that has only a few distant and low-lying hills on it, meaning that the view north is clear of any obstructions. We had a very productive time there and also at another couple of locations nearby and came away with some great shots of the “Merry Dancers”.

Finally, although the equinox referred to as a day by many people, it is actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the sun. For 2021, the Autumnal Equinox will be at 8:21 pm on Wednesday 22 September and the Spring Equinox was at 9:37 am on Saturday 20 March. For me, one of the magical things about photography is its ability to capture scenes and moments in the present for the viewers of the future, before they are lost forever, just like the scene in this photo I took in August 2019 of an old sailing boat high up on the rocks at Samalaman Bay near Glenuig. I am so fortunate to be able to live where I do. This special corner of Scotland is a photographer’s paradise with its diverse landscape of mountains, moorland and woodland and an amazing coastline that is home to beautiful white sand beaches and dramatic rocky shorelines. It is a place that has something to offer the photographer in all seasons and in the summer months, the northern coastline of Moidart and Ardnamurchan is the place to go with the camera. In these months, the late evening sun sets in the northwest and brings beautiful sunsets to this part of the West Highland Peninsulas.

r a few years, an old sailing boat had sat perched high up on a huge, rounded rock on the southern edge of the bay, in a position such that it combined with the edges of the bay and the distant silhouette of the Small Isles to create the perfect composition. I visited the bay on a perfectly still August evening in 2019 when a high spring tide coincided with sunset. Even with almost 5 metres of tide, this old sailboat was high enough up on the rocks to remain steadfast in its position. After taking in the scene for a while, I set up my camera on its tripod, set the exposure time to 90 seconds, pressed the shutter button to capture and freeze 1½ minutes of the most magical west coast sunset to create the image at the top of this blog titled “On the Rocks I”.

When I now visit this spot in Samalaman Bay, it certainly feels that something is missing. That old boat sure was essential to the picture-perfect scene that I captured and although I was saddened at its departure, I seek great comfort in knowing that I did manage to capture it before it was gone forever. To me, this ability to capture the present for the viewers of the future is the power of photography and is summed up by this quote by Karl Lagerfeld: “What I like about photographs is that they capture a moment that’s gone forever, impossible to reproduce.”

Once rare noctilucent, or “night-shining” clouds are becoming a more common feature of our summer night sky and the increased presence of these ghostly whispers of light shimmering high up in the Earth’s atmosphere is thought to be as a result of human-caused climate change. Although this is certainly cause for concern, the sight of them is quite mesmerising and if you are a night owl, it is a sight that is not too difficult to photograph. In the 8 or so weeks either side of the Summer Solstice, which this year was on 21 June, the days are long and the nights are short. In fact, the sun gets to no more than 10-15 degrees below the horizon and this makes it a lean period for both aurora chasers and stargazers because astronomical, or full darkness does not occur at any point during the night. The resulting all-night twilight means that it is simply too light to see the “Merry Dancers” and all but the brightest stars. However, all is not lost because what you can see are noctilucent, or “night-shining” clouds. They become visible in the north to north-west sky as darkness falls and just as the brightest stars become visible. They have the appearance of ghostly whispers of light shimmering in the all-night twilight and are usually set against a pearly-blue sky. These night-shining clouds are the highest clouds in Earth's atmosphere. They form in the middle atmosphere, or mesosphere, roughly 80 kilometres (50 miles) above Earth's surface. They are thought to be made of ice crystals that form on fine dust particles from meteors and volcanic activity. These ice coated dust particles then reflect the light that the sun projects high up into the sky, when it is between 6 to 16 degrees below the horizon, to create an illuminated cloudy veil in the northern sky at latitudes between ±50° and ±70°. They are first known to have been observed in 1885, two years after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, but it remains unclear as to whether their appearance had anything to do with the volcanic eruption or whether their discovery was due to more people observing the spectacular sunsets caused by the volcanic debris in the atmosphere.

This does indeed give me cause for concern, but nevertheless, the sight of these shimmering and wispy clouds illuminating the upper reaches of our summer night sky is quite mesmerising. I was fortunate enough to both see and photograph them on a mid-July night at Castle Tioram when it barely got dark. They seemed to not only illuminate the sky but also the landscape around me. There is still time to see them so, if you are outside after midnight on a clear night, look north and you may be able to pick them out. If you have a modern digital camera fitted with a wide-angle lens which you can mount on a tripod, you can try taking some photographs of them yourself. Put the camera on the manual setting, open up the aperture to at least f4, set your ISO 800 and take a few test shots at exposures of several seconds until you find the exposure time that works. You could even try photographing them with your smart phone if it has a “Night Mode” setting.

Views of the Small Isles of Muck, Eigg, Rùm and Canna are ever-changing as you make the journey from east to west along the coast of Moidart and north Ardnamurchan and past its spectacular cliffs, dramatic rocky shores and beautiful white sand beaches. While the dramatic peaks of Rùm’s Cuillin Mountain range are ever present, the distinctive profile of Eigg and its highest hill, An Sgurr, is a prominent feature at first, but it gradually disappears from view to be replaced by the more diminutive profile of Muck as you reach the journey’s end……. IntroductionScotland has 40 National Scenic Areas which cover 13% of its land mass and they earn this designation because their outstanding scenery makes them the country’s finest Landscapes. One of these areas is Morar, Moidart and Ardnamurchan here on Scotland’s north-west coast. It is home to a coastline of spectacular cliffs, dramatic rocky shores and beautiful white sand beaches. Added to all of this are breath-taking views of the Small Isles of Muck, Eigg, Rùm and Canna, which sit a few miles west out in the Sound of Arisaig and just south of the Isle of Skye. As you travel from Moidart in the east, to Ardnamurchan in the west, your perspective of the Small Isles changes significantly, with both them and features on them coming into view and disappearing again after only a few miles. This everchanging view makes photographing both them and this coastline an absolute joy and now that the evening sun is in the north-west, my plan for the coming weeks is to photograph to do just that. My aim is to capture this spectacular coastline while it is bathed in warm sunlight at the end of our long summer days. In the meantime, however, I thought I would describe this somewhat special journey and share some of the images that I already have. Moidart

On reaching Glenuig, you can turn off the main road, drive past the Glenuig Inn and continue westward for about a mile and a half to reach the road end. From there, a short walk takes you to Smirisary, an isolated and roadless crofting village that sits between a rocky foreshore and a steep hillside about two miles to the west of Glenuig. As you walk the final half mile to the village, your view of the sea is obstructed by a small hill, but as you get to the top of it, the view dramatically opens up to reveal islands that you feel you can almost touch (Image 3). I like to visit Smirisary in mid to late summer. It is a great place to capture Muck, Eigg and Rùm sitting in flat calm seas while they are silhouetted against the colourful skies that are a feature of the sunsets there at that time of year. From there, you get a closer view of the distinctive shape of An Sgurr and the dramatic peaks of the Rùm and its Cuillin mountain range, which sits behind Eigg and simply adds to the magic you are witnessing (Image 4).

East ArdnamurchanIf you want to get a view of the Small Isles on this part of your journey, you need to head out to the small but beautiful sandy beach at Ardtoe where a short walk out to the headland on its western side brings the southern end of Eigg and An Sgurr back into view. From there, you also get a glimpse of Rùm because the high peaks of the Rùm Cuillin are just visible above the land that shelters the beach from the open sea (Image 1 and Image 7). While at Ardtoe and if you don’t mind a walk over uneven and often boggy ground, you can make your way out to the end of Rubha Luinngeanach where you get a more open view of Eigg with Rùm behind it. It was at this spot where I witnessed what I think is the most spectacular sunset I have ever seen over the Small Isles (Image 8). I was out there on a rather cloudy July evening, so my hopes of getting a good image were not high. Suddenly the clouds beyond the skerry of Sgeir an Eidigh parted and allowed the most intense of crepuscular rays to shine down on the Isle of Eigg and silhouetted it against the golden backdrop that they had created. It is a moment that is forever etched on my memory. On leaving Ardtoe to head back towards Acharacle, you’ll find that a slight diversion down the road towards Arivegaig rewards you with a fine view out through the entrance of Kentra Bay to Eigg, where An Sgurr sits directly behind the gap between the land and the sea (Image 9). The road to Arivegaig is also a spot where you can catch a full moon setting behind the Rùm Cuillin on a clear winter morning (Image 10). West ArdnamurchanThe next part of the journey west takes you along the side of Loch Sunart and it is a good few miles before you see the Small Isles again because the road now takes you along the southern coast of the Ardnamurchan Peninsula. It is not until you pass Camas nan Geall and follow the road north around the side of Ben Hiant to reach Doire Daraich before they come back into view again (Image 11). Given how far west you have travelled to reach there, the perspective is now very different because Eigg now sits to the right of Rùm, while the drive down to Kilmory brings the Muck back into view as reach the phone box just before the village (Image 12).

It is from the hills above Portuairk from where I think you get the most dramatic view of Rùm and the magnificent peaks of its Cuillin mountain range. It is simply majestic, sitting there beyond Sanna Bay and the significantly more diminutive Isle of Muck (Image 15). While there, it is well worth taking the walk from Portuairk to the beautiful white sand beach at Sanna because, as you climb over the hill that separates the two, another magnificent view of the Small Isles reveals itself (Image 16). It is from there that you can see all the Small Isles because the fourth and, up until now, elusive Isle of Canna reveals itself. If you stop there for a little whole and look north over the beach you can just make it out, sitting well out the west of the Isle of Rùm, which has Eigg to its east and Muck to its south. Journey’s EndOur journey from east to west along this beautiful Moidart and Ardnamurchan coastline ends at Ardnamurchan Point. It is as far west as you can go on the British Mainland and is home to the iconic Ardnamurchan Lighthouse which so many visitors head for when they visit the West Highland Peninsulas.

While you do get a clear view of the Small Isles from there, they do not readily sit in any photographic composition that features the lighthouse because the camera tends to point in a direction looking away from them or is at an angle where the islands are hidden by the lighthouse itself. It takes a walk out on to the rocks of Dubh Rubha Mor at low tide before you can point the camera north, across the bay of Briaghlann, and capture both the lighthouse and the now familiar profile of Rùm and Muck behind it and it seems fitting that I end this journey with an image of the sun setting on this very scene (Image 17). With some time to spare after travelling back across the Corran Narrows on the ferry, I found myself up at the Ardgour War Memorial looking at signs of something that had gone before which had been a small part of a huge military project that is thought to have played a key role in bringing World War I to an end …. Time on my HandsLast week, I found myself with an unexpected hour or so to spare at Corran Point, so decided to go for a walk and find the Ardgour War Memorial, which is located up on a bank just south of the lighthouse and above the road. The main reason for doing this was to scout out the location in advance of me going there at some point after dark to photograph the Memorial under the stars. This is something that I do when preparing for most of my night shots as it is so much easier to figure out a composition in daylight than it is in the pitch dark. Having walked from the Corran Ferry, I reached the bend in the road by the Lighthouse and followed a track up into a field beyond a metal gate. I found the War Memorial at the top of a bank overlooking Loch Linnhe, with expansive views all the way down its full length to the south. The Memorial itself is typical of the many that you find scattered across the Highlands, consisting of a granite Celtic cross and plinth mounted on a base of what seemed to be made of local stone.

Gradually, I began thinking ahead to my future shot of the War Memorial under the stars and, eventually, I began looking at different shot angles of the Memorial to see if I could find some compositions that might work for the photograph that I had in mind. My plan is to take it later in the year when the Milky Way will be at its best, with its cloudy core above the horizon in the south to south-west sky. My aim is to produce something similar to these two shots that I’ve taken of the Strontian and Moidart war memorials in previous years. While doing this, I noticed that the Memorial’s stone base was sitting on what appeared to be a metal ring with several bolts protruding from it. You can see the metal ring and bolts in the picture below and the more that I thought about them, the more I couldn’t help wondering what they had been used for. Playing on My MindThis played on my mind for a day or two, leading me to do a bit of research to find out more about them. After looking at a few sources, I found some information in the Highland Historic Environment Record, that suggested that a gun battery was built on that spot in 1917, to provide protection for the United States ships unloading naval mines at Corpach that were then transported in smaller boats through the Caledonian Canal to the US Naval Base at Inverness. Further research uncovered a report titled “The Built Heritage of the First World War in Scotland” that was commissioned by Historic Scotland which confirms that the gun battery was built there and that it comprised two 15-pdr guns and one 7.5-inch howitzer bolted down onto steel rings called holdfasts, which were set into plain concrete slabs. It turns out that the War Memorial was built on one of these concrete slabs and the steel ring at its base is one of these holdfasts. The Imperial War Museum does have a photograph of the gun battery which was taken in 1918 and shows the Royal Marine Gun Crews manning the guns. In it, you can see that there is no parapet around the guns and that the ammunition for them was stored in wooden lockers close by. I’ve asked the Imperial War Museum for a licence to publish this photograph and hope to be able to share it with you at some point. A Small Part of a Big PictureAnother question came to my mind while I was researching all this – Why was the United States Navy shipping naval mines to Corpach and then transporting them up the Caledonian Canal to Inverness? Well, the answer is that the mines were being used in the North Sea Mine Barrage which was a large minefield laid easterly from the Orkney Islands, right across the top of the North Sea to Norway with the aim of preventing the U-Boats making their way from their bases in Germany and out into the Atlantic to attack the convoys that were bringing supplies from the United States to the British Isles. Laying this mine barrage was a huge undertaking and until World War II, it was the largest ever laid. It spanned the entire 230-mile width of the North Sea from Orkney and Norway and was between 15 to 35 miles wide. The Allied Forces began laying the mines in June 1918 and within a matter of a few months they had laid just over 70,000 of them at a total cost of just over £1bn in today’s money. The barrage was considered to be a great success and is credited with the destruction or damage of up to 21 U-Boats, but probably its greater effect was in shattering the morale of German submarine crews, thus helping to bring about the revolt of German seamen that marked the beginning of the defeat of Germany in World War I. Hidden HistorySo there you have it, a tiny little bit of history hidden beneath the Ardgour War Memorial in the form of a steel ring and some bolts giving a small clue of something that went before. I would never have thought that these incongruous bolts would have been part of what today would be the equivalent of a £1bn military project that is thought to have played a key part in bringing World War I to an end. A war that left more than 16 million people dead and also helped to spread one of the world’s deadliest global pandemics, the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 20 to 50 million people. Poignant, very poignant indeed.

We’re coming to the end of this winter. One during which we had the coldest January since 2010. One of snow and of cold and clear weather and one that has been productive from a photographic perspective. See some of the images I’ve captured and find out a bit about the story behind them…. How Do You Cope with all the Snow?We are fast approaching the start of Meteorological Spring (March, April and May) and also the end of my fifth winter since moving to the Peninsulas. There is a noticeable difference in the hours of daylight as the nights shorten and it will not be long before the landscape begins to spring back into life. I find myself thinking back on the winter months of December, January and February; and also a question I’m often asked by people visiting – “How do you cope with all the snow in winter?” Why this question gets asked always intrigues me. It seems to always happen when standing on the decking outside my studio looking at Loch Sunart and all the hills that surround it. Could it be because this remote and rugged landscape looks foreboding? Could it be because we are well north of where most people live? Who knows? Well, whatever it is, my answer is always the same - “It’s never a problem here as we don’t get that much snow and when we do get it, it is usually only high up on the hills. In fact, if the snow does fall down here at sea level, it only lasts a day or two at the very most and I guess that being on a bit of land that sticks out into the sea on the west coast means that the Gulf Stream keeps the temperatures up”. This is indeed true and it is complete contrast to the snowy winters I experienced when growing up on the east side of Scotland when, in the days without central heating, thick frost would form on the inside of the windows and we’d need to scrape a little hole in it to reveal what was outside. I do miss “proper” winters like that, but looking back over the last few months, it certainly feels as if we’ve had one this time. In fact, we’ve just had our coldest January since 2010, with the average temperature recording in Scotland being 0.6°C while my weather station here at Resipole recorded an average of 2.9°C. The strong northerly air flow that brought the low temperatures also brought substantial sunshine with it and plenty of cold, crisp and clear days on which I just had to get out with the camera. First Snow and Winter InspirationLooking back through my images from the last few months reminded me that this “proper” winter weather was not just limited to January. Indeed, we saw our first snow at the end of November while having a staycation at Kingairloch Estate over on the east side of the Peninsulas. We woke up on a morning towards the end of our week away to see snow on the distant high peaks of Glencoe and the Mamores. This prompted a drive up the shore of Loch Linnhe to get a closer look. The snow-capped mountains looked lovely under the clear blue sky and we just had to stop at Lochan Doire a' Bhraghaid to take in the view. From there you get a fantastic view of Ben Nevis because you can see it through a gap in the hills above Inversanda. While there, I took this shot of the snow-covered slopes of Ben Nevis, some 17 miles to the north and made a mental note to myself to come back at some point and capture it when it had the first light of a winter day on it. Searching for Some LightThis first of the winter snow on the hills lasted for just over a week, but before it disappeared, I headed to West Ardnamurchan and up to a spot high on the slopes of Beinn Bhuidhe above Glenmore. It’s a great place to capture panoramic views of Loch Sunart or use a long lens to not only pick out elements of the high hills of Morvern on the other side of Loch Sunart, but also of Loch Teacuis, which cuts its way southwards into them. Unfortunately, I always seem to time my visits to the slopes of Beinn Bhuidhe on days when the light does not want to do what I need it to do. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve left Resipole under promising looking skies only to arrive at my spot and find thick cloud and no light on the landscape. I thought that this time was going to be another like that because thick cloud greeted me on my arrival. As I followed the path up to Beinn Bhuidhe, I kept looking at the cloud filled sky in the hope that it would clear a little and let through some light, but it didn’t. Undeterred, I set up at my chosen spot and sat for about an hour, sheltering as best I could from the biting easterly wind, while looking through the long-lens I’d fitted to the camera in search of some compositions that might work if the light did appear. I had almost given up hope, but in the few minutes before the sun was due to dip below the hills to the south-west, a small gap appeared to let a patch of light fall on the snow-capped peak of Beinn Iadain, one of the high peaks of Morvern. The resulting image shows the peak of Ben Iadain sporting a crown of golden light with the north facing slopes of Beinn Ghormaig, the Isle Carna and the Isle of Risga sitting in front of it. An Afternoon of SerendipityThankfully, not all my shots are so hard won and occasionally good fortune smiles on me. In early December, a few weeks after my time on Beinn Bhuidhe, I had a batch of Christmas orders to take to the Post Office in Acharacle and while packing them all into the car, I could not help but notice some hints of colour appearing in the sky to the west. It looked promising, so I decided to take my camera gear with me just in case. I sure wasn’t disappointed with what unfolded. As I drove down into the village, I could see the mist beginning to form in the air above Loch Shiel, so instead of going straight to the Post Office, I took the short detour down to the jetty in village to check out the conditions on the loch. As I stood on the jetty, I watched the pinks and purples of a winter sunset intensify while mist rolled down the loch and I couldn’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of calm, as well as whole load of good fortune about my decision to take my camera gear with me. I was there for well over an hour, photographing scenes in different directions and under different light conditions before deciding that I really needed to get to the Post Office before it closed. Both jobs done. Parcels posted and a number of “keepers” captured including this panoramic image of the sunset colours at their peak. A Plan Comes TogetherFinding myself in January and in a new year, my mind was still set on capturing the shot of the first light of the day on the snow covered peak of Ben Nevis. The shot that I had thought of when I saw the first snow of this winter on the hills back in November. With clouds usually covering its summit for nearly 80% of the winter months, photographing Ben Nevis sure turned out to be a bit of a wating game. There needed to be a clear morning during a spell of the weather cold enough to put snow on the Ben and freeze the surface of Lochan Doire a' Bhraghaid. Finally, at the start of the second week in January, the conditions seemed very promising and I headed up into the hills above Inversanda for sunrise in the hope that I’d get the shot I was looking for. Setting up in the dark, I couldn’t see if Ben Nevis was clear of cloud, but the moon and stars above my head suggested that it could be. As I waited for the first light of what was a very cold January morning to appear, the mountain began to emerge from the darkness and it looked as if my luck was in. Eventually, the first light of the day shone on its south facing upper slopes and there was just enough cloud to enhance the pink of the sunrise which, even at a distance of 17 miles, was reflected back onto the frozen surface of the lochan. I love it when a plan comes together. Time for a Plan BThe last week in January brought a few days of very heavy snowfall which, very unusually left a couple of inches of the white stuff all the way down to the seashore. Equally unusual were day and night-time temperatures so low that the snow at sea level did not disappear. As I watched successive tides wash fresh falls of snow from the loch shore, I thought that an image of snow lying on a sandy beach all the way down to the water would be worth capturing and that the beach at Ardtoe would be a great place to do it. With this in mind, I awoke early on a morning after heavy overnight snow had been forecast. On opening the curtains to a freshly snow-covered landscape, I decided to head out to Ardtoe. With much anticipation, I left the house but as I drove closer and closer to my destination the clear skies became more and more obscured by mist. This is not unusual because the low ground around Loch Shiel often cradles mist on cold and still winter mornings. So undeterred, I continued my journey to the beach as experience suggested that it would be clear there. However, it was not to be and I was greeted by a snow-covered beach shrouded in thick mist. The more I waited for the mist to clear, the thicker and thicker it seemed to become, so I eventually decided to head home. On the drive back through a beautiful snow-covered landscape, I thought that the conditions were too good to submit to failure and began racking my brains to figure out a place where a combination of misty conditions and fresh snow fall could work together. I eventually decided to take a small detour to the old bridge over the River Shiel at Blain to see what it was like there. When I arrived, I was not disappointed. The scene was stunning with all the trees covered in the freshly fallen snow and some beautiful light fighting its way through the mist behind the bridge. After an extremely productive half hour, I left with a few images, including this one of the bridge, with the river beneath it coloured by golden light fighting to break through the mist behind it. Thank heavens for a little local knowledge and for figuring out a Plan B. A Winter I Will RememberIt’s been a winter just like the ones I remember from my childhood. I’ll remember it not only for its snow and its cold, clear days but also for it being a winter that has given me an extremely productive time for my photography. The images I’ve included in this blog are just a small sample of those that I’ve captured and if you’d like to see more, you can find the in the Recent Images Gallery on this website. I hope you enjoy them.

|

AuthorHi, Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved