|

When I moved to the Peninsula, after living for almost 30 years in and around Glasgow, I was immediately blown away by the number of stars I could see in the sky on a dark, clear night. Seven years have passed, and I still get awestruck by the sight above me when I am out under a night sky. This is especially true at this time of the year, when our planet is facing inwards to the core of our galaxy, the Milky Way. So, this month, I thought I’d share a few tips for exploring our night sky, which is so dark that you can see over 7000 stars with the naked eye. So how dark is a dark sky? Well, I have measured the darkness of the sky at various locations on the Peninsula using a device called a Sky Quality Meter (SQM) and obtained readings of between 21 and 22.5. To give you an idea of what this means, you would get a reading of around 8 in the middle of a major city such as Glasgow or Edinburgh and a reading of 24 would be measured in a photographer's dark room. So on some night, we are very near to total darkness, meaning that the Peninsula is a great place to enjoy a spot of stargazing. Where to Go

Castle Tioram, Moidart: Turn off the A861 just north of Acharacle and 2 miles down a narrow single track which should be driven with care. Once there you get good lines of sight in all directions except East. From the shore a little north of the car park, you can look out south and west to see the Milky Way and look North to catch the Northern Lights. Do not go out to the Castle as you may get caught out with the tide. Old Boat House, Ardtornish Estate, Morvern: A flat area of hardstanding, located between the shore and the track to Ardtornish Castle about 200 metres before the Old Boathouse on the shore of Lochaline. Park in the Estate Farm Courtyard where their Gift Shop is located and walk to the area near the boathouse from there. Ardnamurchan Lighthouse: Anywhere within the grounds of the Lighthouse Visitor Centre complex, but stay on the designated paths, picnic areas and carparks as this will keep you away from cliffs and sharp drops into the sea, which you must avoid in the dark. Clear views of the sky in all directions and the darkest place on the Peninsula due to its most westerly location. Bear in mind that overnight parking is not permitted on the site. When to GoThe best time to start stargazing is from 2 hours after sunset, when the sky is as dark as it gets. Also, it is best to do it in the week either side of a new Moon, when there is little or no moonlight to spoil the show. You can check the Sun and Moon times at www.thetimeandplace.info to decide what time is best and if you do go out: Use your naked eyes – You can see a lot with just your naked eyes, just give them 10-15 minutes to adjust fully to the dark and you’ll suddenly find that you’ll see twice as many stars. Use a red torch – Once your eyes have adjusted, avoid using bright white lights because it is very easy to lose your “night vision”. Instead use a red headlight or torch because this doesn’t affect you night vision. Stay warm – Clear, dark nights are often very cold, so wear plenty of layers, a hat and gloves and think about using heat wraps or charcoal hand warmers. Use Star Charts – These can be downloaded free from www.skymaps.com. You can also use one of the many smartphone apps that are available. I find Pocket Universe very good. What to SeeWhen you are out, the things to look out for are:

Milky Way – Look directly overhead during autumn and early winter evenings and you'll see this shimmering river of light streaming through the constellations of Cassiopeia and Cygnus. Northern Lights – They can happen at any time of the year, but the best time is around the autumn and spring equinoxes because the geomagnetic activity that causes them hits the Earth’s atmosphere at just the right angle. Check the AuroraWatch UK website for alerts. Stars and Constellations – Look south in the next few months and you’ll see the grand constellations of winter: Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Perseus, Cassiopeia, Gemini, and Canis Major. They are rich with stars and star clusters, with the most brilliant stars being Capella, Castor and Pollux, Procyon, Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, and Betelgeuse. Planets – You’ll be able to find each of the visible planets of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn at some point throughout the year. However, their position in the sky each month varies from year to year, so do check a night sky guide to find out which ones you will see. Meteor Showers – They happen at predictable times throughout the year. Look out for the annual Quadrantids (January), Lyrids (April), Perseids (August), Orionids (October), Leonids (November) and Geminids (December). When looking for them, spend at least an hour outside doing so because they tend to happen in fits and starts and beforehand, check the meteor shower guide at www.earthsky.org for the best times to look. Finally, you can learn more about what to look for by checking out my monthly night sky guides on this website, which you can find by clicking here.

2 Comments

The image below was taken on a September night at the Loch Shiel jetty in Acharacle when I had a client with me for some night photography tuition. We had been photographing the Milky Way in the sky over Loch Sunart when the Aurora Alerts went off, so we decided to head over to the jetty as it has a clear view north. We had a great time photographing the Northern Lights both here and at other locations close by. Some of the images from that night hang in my Studio at Resipole and they often prompt people to ask; “Can you see the Northern Lights here and are they really that green?”. My answer is always yes, but we can only perceive the aurora as a greyish-blue light. I then go on to explain the reason why... It’s all because our eyes contain two types of photoreceptors (cones and rods) and how they work in the dark compared to how they work in daylight. Each retina has about 6 to 7 million cones and they provide the eye with the ability to distinguish colour. However, these cones only work effectively when it is light. On the other hand, there are about 120 million rods. These are far more effective at helping us to see in low light and near dark conditions, but they cannot distinguish colour. So, as it gets dark and the cones stop working, our eyes move from enabling us to see in full colour to only seeing in black and white. This means that anything we look at in the dark, including the Northern Lights, will only be seen in black, white and shades of grey. However, the sensors that you find in digital cameras do not suffer from this limitation and are extremely effective at picking up both light and colour in the dark. They can easily pick up the greens, reds, blues and purples that are present in the aurora, meaning that the colours you see in digitally taken images of the aurora are not a result of any photo editing but are, in fact, real. The auroral colours are a result of collisions between gaseous particles in the Earth's atmosphere and charged particles released from the Sun's atmosphere. The colours present in the aurora depend on the type of gas particles the charged solar particles collide with. Green is the most common because most solar particles collide with our atmosphere at an altitude of around 60 to 150 miles, where there are high concentrations of oxygen and these collisions with oxygen produce a pale yellowish-green colour. Blue and purple can also be present, but far less frequently than green because they only appear when solar activity is strong enough to cause particle collisions in our atmosphere at an altitude of 60 miles or less. At these heights, it is a reaction with nitrogen that causes the aurora to be tinged with purple or blue. On rare occasions, red can be present in the aurora, but only when the Sun’s activity causes solar particles to react with oxygen at altitudes above 150 miles or so. At this height the oxygen is less concentrated and is “excited” at a higher frequency or wavelength than the denser oxygen lower down in the atmosphere and so produces a purely red aurora. To give you an idea of the difference between what we can see and what the camera sees, I’ve prepared two versions of another image taken that night, but at Castle Tioram rather than Loch Shiel. These two versions are below, with the one on the left showing what the camera saw and the one on the right showing what I saw when I was taking the photograph. Don’t despair though, as but there is a way you can experience the colours for yourself. Many modern phone cameras have a “Night Mode” setting that allows you to take bright, sharp and noise-free photos, even in the darkness of the night. So, the next time you hear of the aurora happening, head to a place with a clear view of the northern horizon, put you phone camera in “Night Mode” and use it to help you see the colours of the ‘Na Fir-chlis’. You will find a few more images of the Northern Lights in the “Our Night Sky” photo gallery on this website and if you’d like to arrange some night photography tuition, please feel free to get in touch.

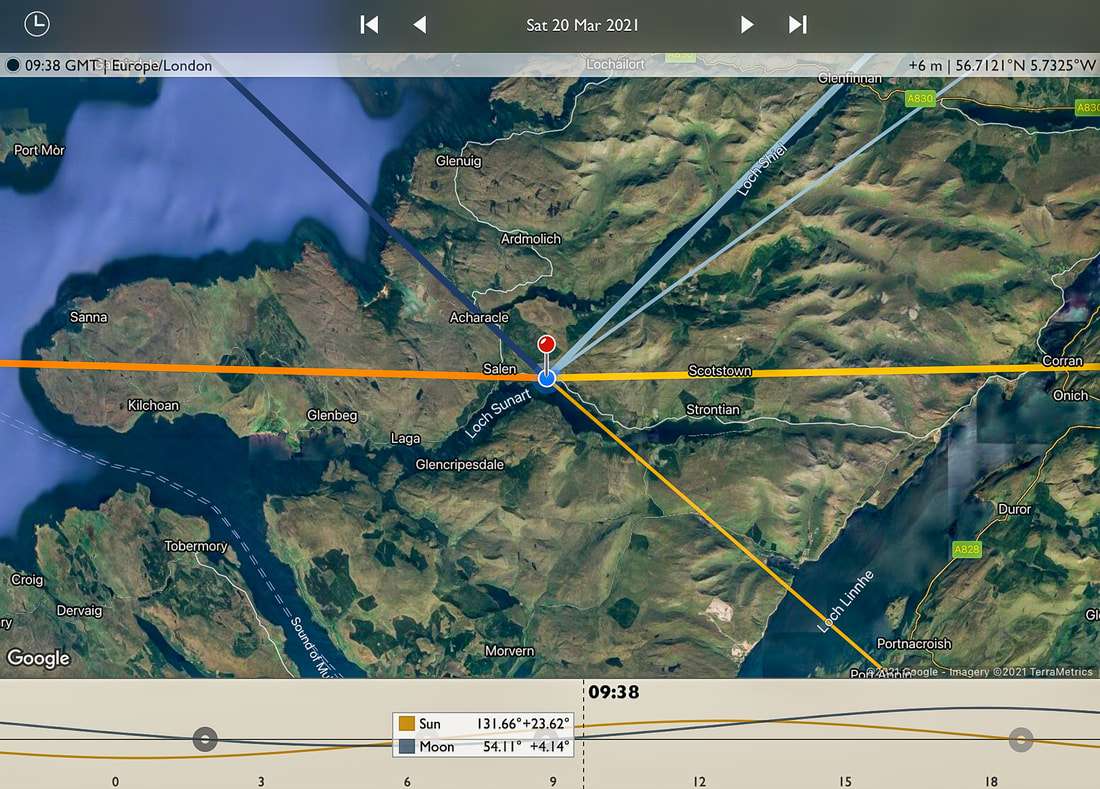

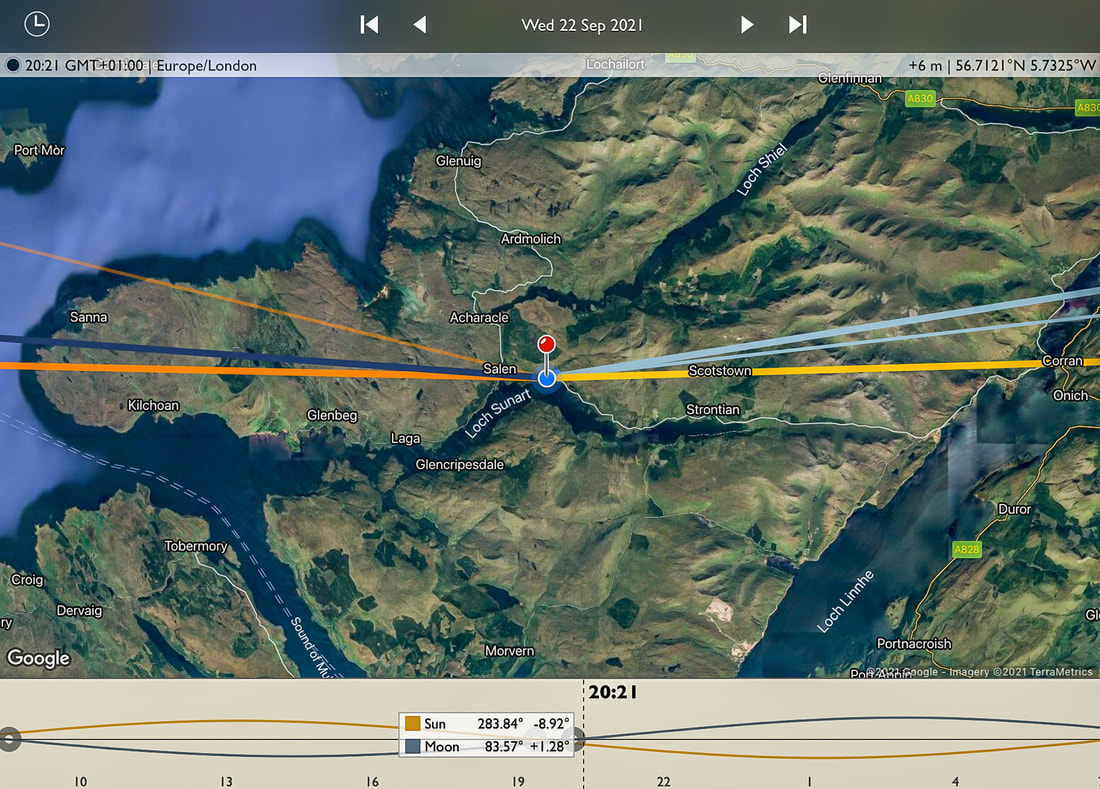

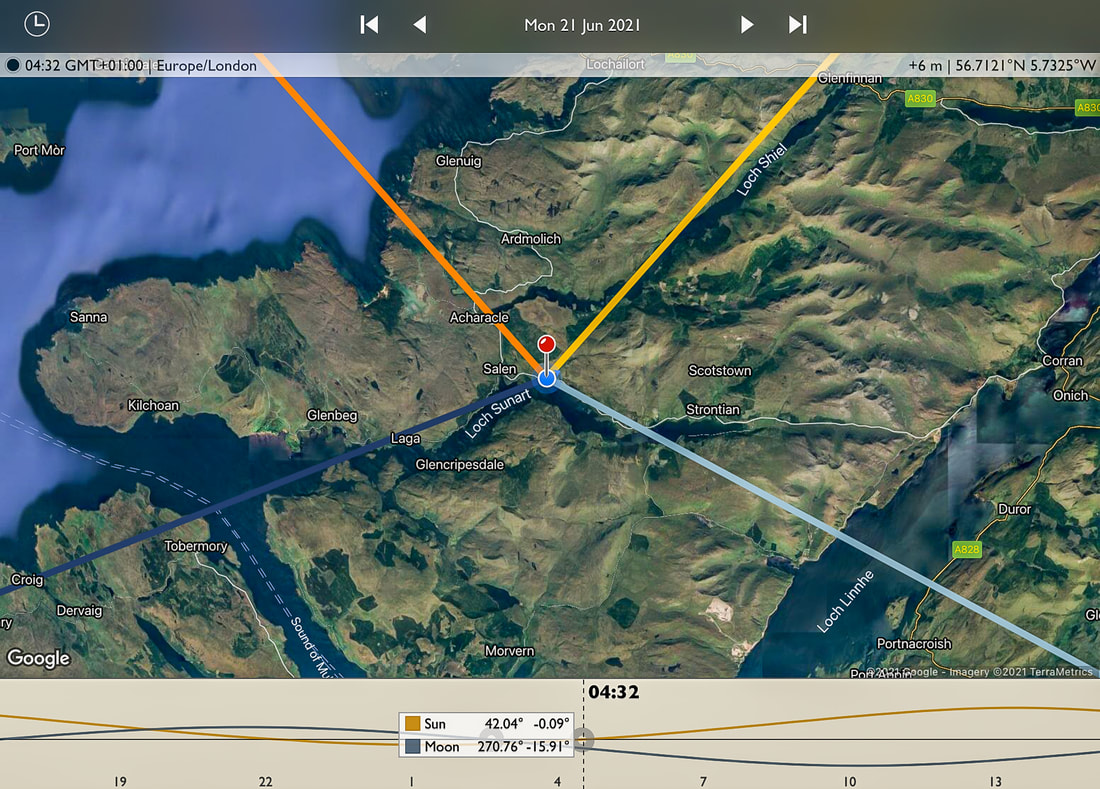

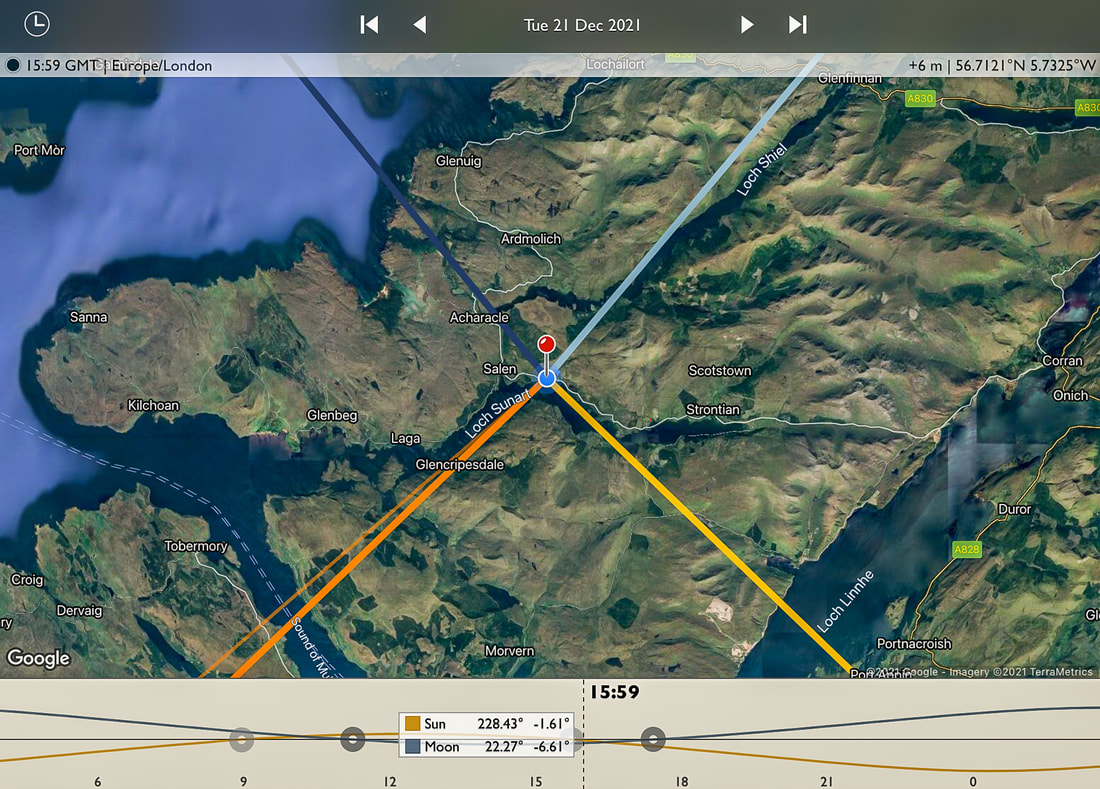

Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or on the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and is when day and night are of equal length and when the Sun rises due east and sets due west. Although this means that the dark nights return, it does mark the beginning of the beautiful sunsets over Loch Sunart that we get here at Resipole during the autumn and winter months and also increased chances of seeing the Aurora Borealis. Most people know that the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but they may not realise that this is quite a generalisation. In fact, the Sun only rises due east and only sets due west on two days of the year; the days of the Spring Equinox and the Autumnal Equinox which, for 2021, are March 20 and September 22. To illustrate this, Figures 1 and 2 show the location of the rising and setting sun at the Spring Equinox and Autumnal Equinox, respectively. Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Image 1, at the top of this blog, was taken at Resipole during sunset on the day after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, with the camera facing southwest down Loch Sunart towards the Isle of Carna and the hills of Morvern. If you look closely, you can see a patch of intense colour behind the wooded hillside on the right-hand side of the image. This was the spot where the sun was setting due west and for me, such a sight is one of the most welcome of the year because it marks the return of spectacular sunsets to this part of the Loch. With the passing of the autumn months and the movement of the setting sun towards the south, these sunsets become more and more intense. They are something that I’ll never tire of photographing even though I have taken countless photos of them from this spot. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen the same mix of colours twice. Each sunset is different because of the varying position of the sun and the infinite range of possible cloud formations that reflect the light from the sun and produce the kaleidoscope of colours. The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Image 2 above was taken 4 days after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, when I had a client out with me for some night photography tuition. We had spent the first part of the night preparing for and taking photographs of the Milky Way rising above Loch Sunart and while we were doing this a very high Aurora Alert came through on my phone. We quickly packed up our camera gear and headed up to Acharacle and set it up again on the jetty there is on Loch Shiel. It is a perfect spot to look for and photograph the Aurora Borealis because it faces directly towards northern horizon that has only a few distant and low-lying hills on it, meaning that the view north is clear of any obstructions. We had a very productive time there and also at another couple of locations nearby and came away with some great shots of the “Merry Dancers”.

Finally, although the equinox referred to as a day by many people, it is actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the sun. For 2021, the Autumnal Equinox will be at 8:21 pm on Wednesday 22 September and the Spring Equinox was at 9:37 am on Saturday 20 March. |

AuthorHi, Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved