|

The vernal (spring) equinox on 20 March heralds the arrival of spring and it is a great time of the year for observing one of the night sky’s most elusive phenomena: zodiacal light. This light will appear as a false dusk that is created by a triangular beam of light from the Sun being reflected off a fog of tiny interplanetary dust particles when it is beneath the horizon. It’s so difficult to see and many astronomers have never witnessed it, however, I was lucky enough to spot and photograph it at Castle Tioram on a dark moonless night on the first day of March last year. It should be visible on dark moonless nights over the next few weeks, so do keep an eye out for it. Have you ever been outside at this time of the year, looking west and noticed what you think is lingering evening twilight, or the light of a nearby town shining up from the horizon? If so, you may well have seen zodiacal light in the sky and not realised. It is a triangular beam of light that shines along the line of the Zodiac, an 8° wide band that straddles the ecliptic, the invisible path that the Sun traces as it moves around the sky. It is the region of the sky where we can find the Sun, Moon and planets and is only 8° wide because most of the planets have orbits that are only slightly inclined to that of the Earth. The exception is Pluto, whose inclination of 17° takes it out of the Zodiac during part of its orbit. At this time of year, the Zodiac rises steeply from the horizon at dusk meaning zodiacal light does the same. People used to think that it originated somehow from phenomena in the Earth’s upper atmosphere, but today we understand it as sunlight reflecting off dust grains that circle the sun in the inner solar system, along the line of the Zodiac. The grains of dust were once thought to be left over from the process that created our Earth and the other planets of our solar system around 4.5 billion years ago, but in recent years, there’s been discussion about them originating from dust storms on the planet Mars. They are thought to be about a millimetre and less in size, densest around the immediate vicinity of the Sun and extending outward beyond the orbit of Mars and, when sunlight shines on these dust grains, it creates the light we see. The light is fainter than the Milky Way, so the darker the night sky, the better chances of seeing it. It is best to go to a location with little or no night pollution, on a night when the moon is out of the sky and look for it in the west in the hour or two after sunset. If you are lucky, you may spot it as a ghostly pyramid of light rising steeply from the horizon.

The best time to look for it in the coming month will be on the days either side of the equinox (20 March) as this coincides with a New Moon, meaning that there will be no moonlight to drown it out. With Venus and Jupiter, our night sky’s two brightest planets, being low down in the west after sunset, they’ll be visible close to or in the zodiacal light. Shortly after, on 23 and 24 March there will also be a thin crescent Moon sitting in the midst of the triangular beam of light as it shines upwards from beneath the western horizon. If you don’t see it in the next few weeks, you can try again in the autumn, but instead of looking for it in the west at dusk, you need to look for it in the east at dawn. This is because the Zodiac elliptic rises steeply from the eastern horizon at dawn in the autumn instead of rising steeply from the western horizon after dusk in the spring.

2 Comments

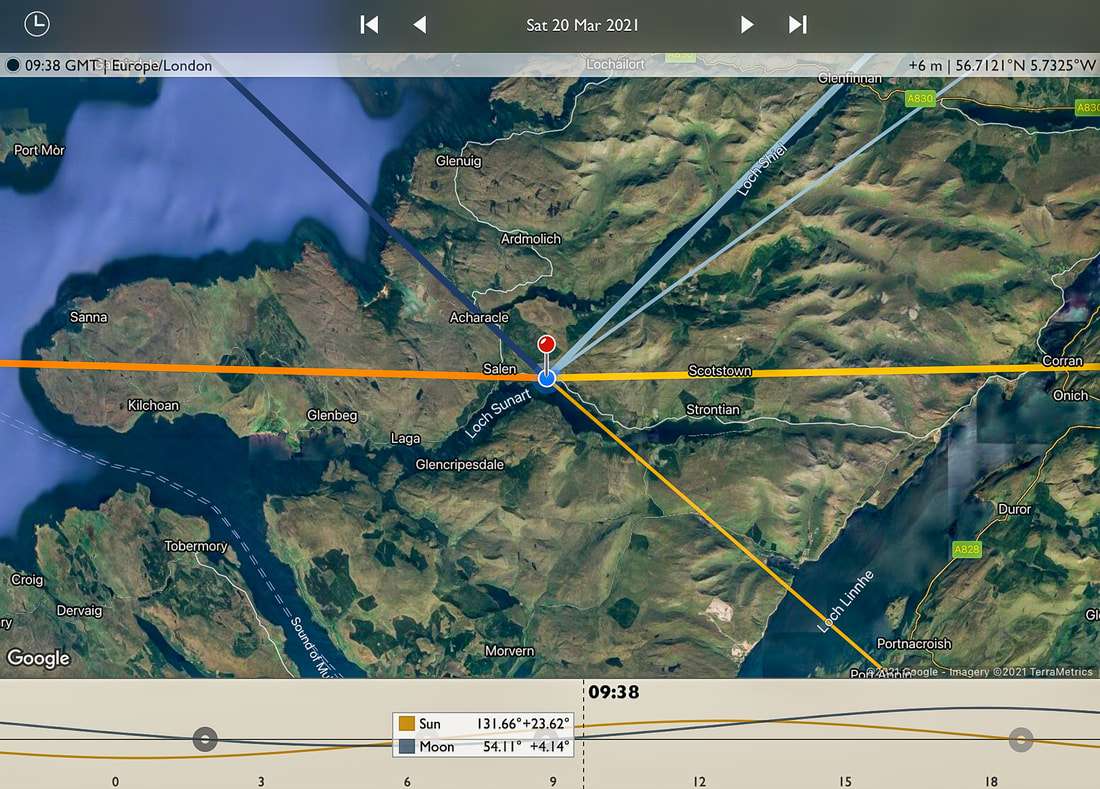

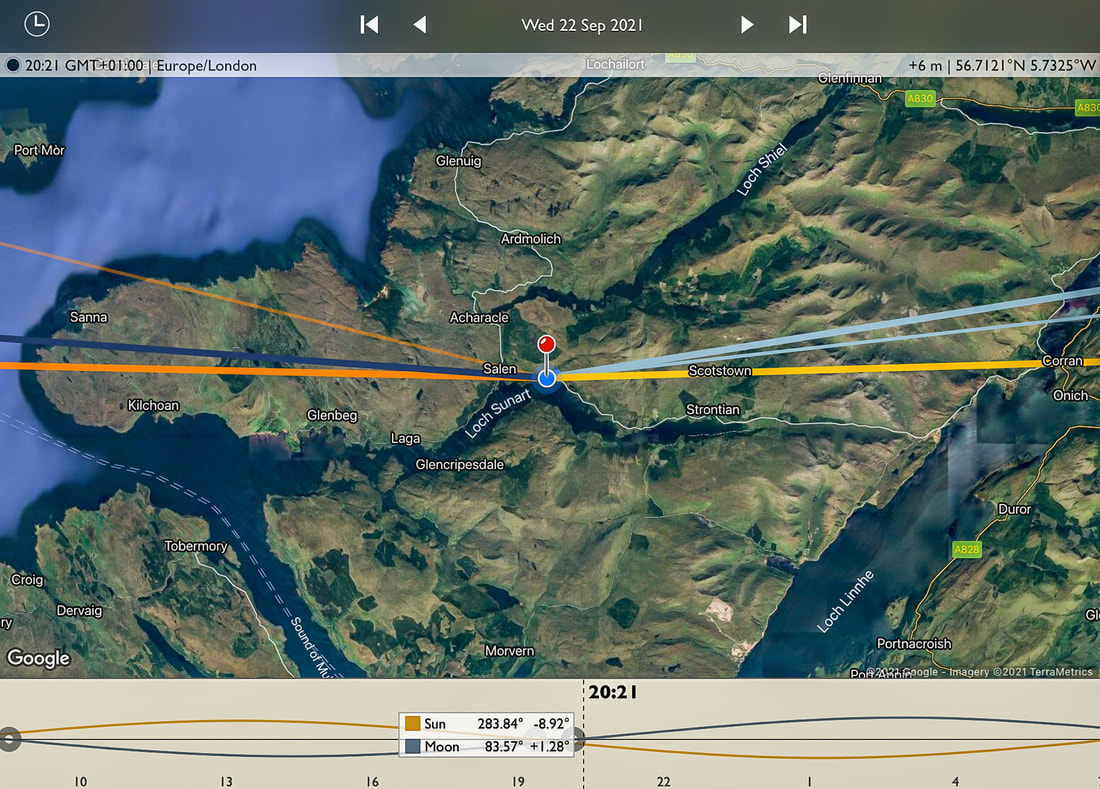

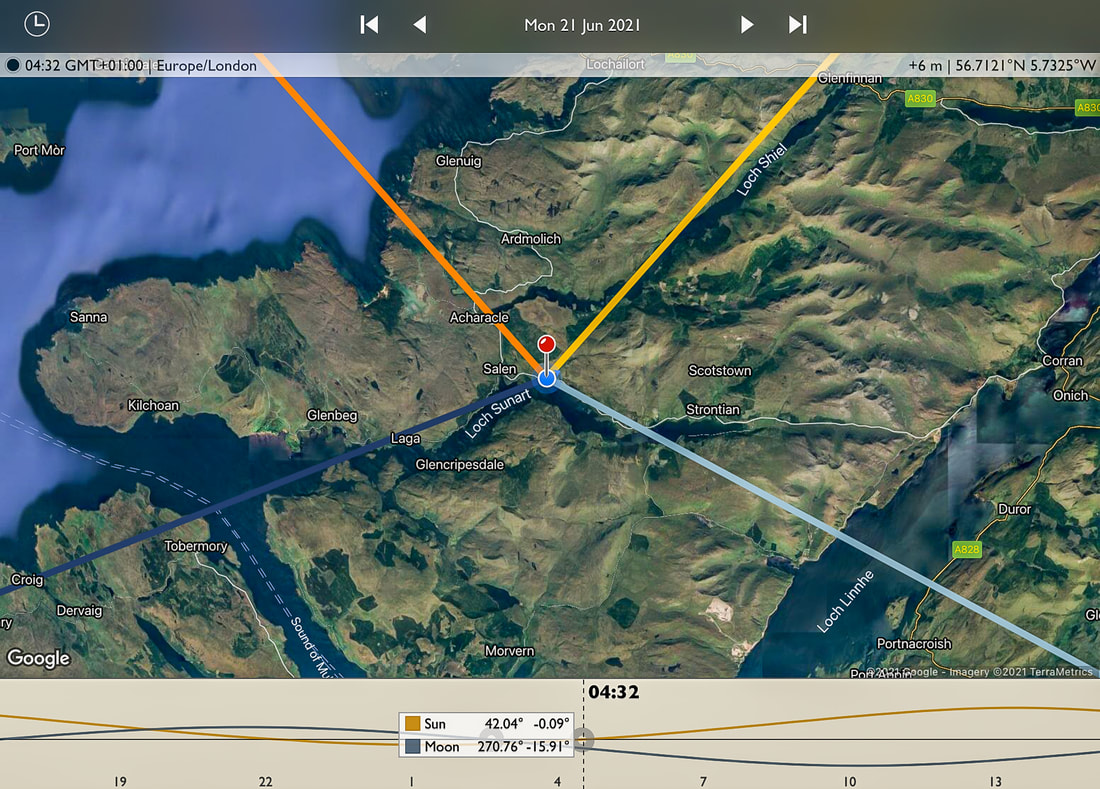

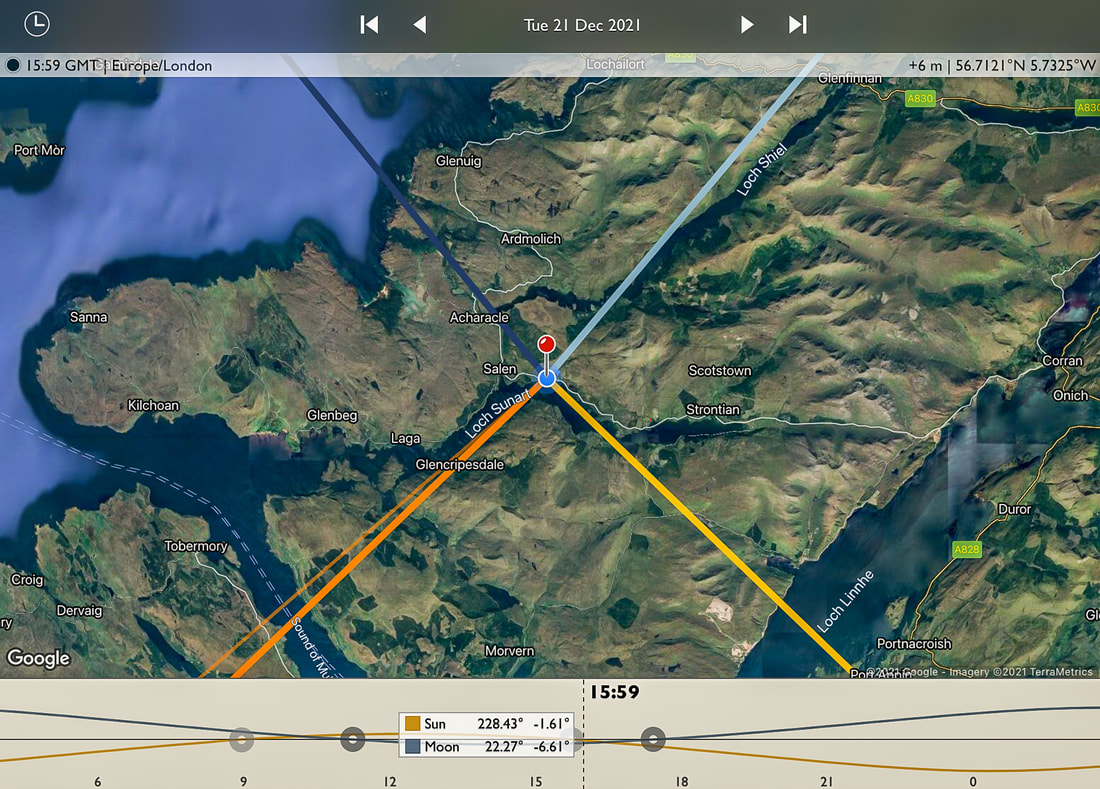

Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or on the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and is when day and night are of equal length and when the Sun rises due east and sets due west. Although this means that the dark nights return, it does mark the beginning of the beautiful sunsets over Loch Sunart that we get here at Resipole during the autumn and winter months and also increased chances of seeing the Aurora Borealis. Most people know that the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but they may not realise that this is quite a generalisation. In fact, the Sun only rises due east and only sets due west on two days of the year; the days of the Spring Equinox and the Autumnal Equinox which, for 2021, are March 20 and September 22. To illustrate this, Figures 1 and 2 show the location of the rising and setting sun at the Spring Equinox and Autumnal Equinox, respectively. Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Once it has risen due east and set due west at the Autumnal Equinox (Figure 2), the Sun rises and sets a tiny bit further south each day until the Winter Solstice, the day on which it rises as far to the southeast as it ever does and sets as far to the southwest as it ever does (See Figure 4). It then changes direction and begins moving north each day, eventually rising due east and setting due west on the Spring Equinox (Figure 1) before continuing northwards until the Summer Solstice, when it rises as far to the northeast as it ever does and sets as far to the northwest as it ever does (Figure 3). Image 1, at the top of this blog, was taken at Resipole during sunset on the day after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, with the camera facing southwest down Loch Sunart towards the Isle of Carna and the hills of Morvern. If you look closely, you can see a patch of intense colour behind the wooded hillside on the right-hand side of the image. This was the spot where the sun was setting due west and for me, such a sight is one of the most welcome of the year because it marks the return of spectacular sunsets to this part of the Loch. With the passing of the autumn months and the movement of the setting sun towards the south, these sunsets become more and more intense. They are something that I’ll never tire of photographing even though I have taken countless photos of them from this spot. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen the same mix of colours twice. Each sunset is different because of the varying position of the sun and the infinite range of possible cloud formations that reflect the light from the sun and produce the kaleidoscope of colours. The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Image 2 above was taken 4 days after the Autumnal Equinox of 2019, when I had a client out with me for some night photography tuition. We had spent the first part of the night preparing for and taking photographs of the Milky Way rising above Loch Sunart and while we were doing this a very high Aurora Alert came through on my phone. We quickly packed up our camera gear and headed up to Acharacle and set it up again on the jetty there is on Loch Shiel. It is a perfect spot to look for and photograph the Aurora Borealis because it faces directly towards northern horizon that has only a few distant and low-lying hills on it, meaning that the view north is clear of any obstructions. We had a very productive time there and also at another couple of locations nearby and came away with some great shots of the “Merry Dancers”.

Finally, although the equinox referred to as a day by many people, it is actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the sun. For 2021, the Autumnal Equinox will be at 8:21 pm on Wednesday 22 September and the Spring Equinox was at 9:37 am on Saturday 20 March. |

AuthorHi, Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved