|

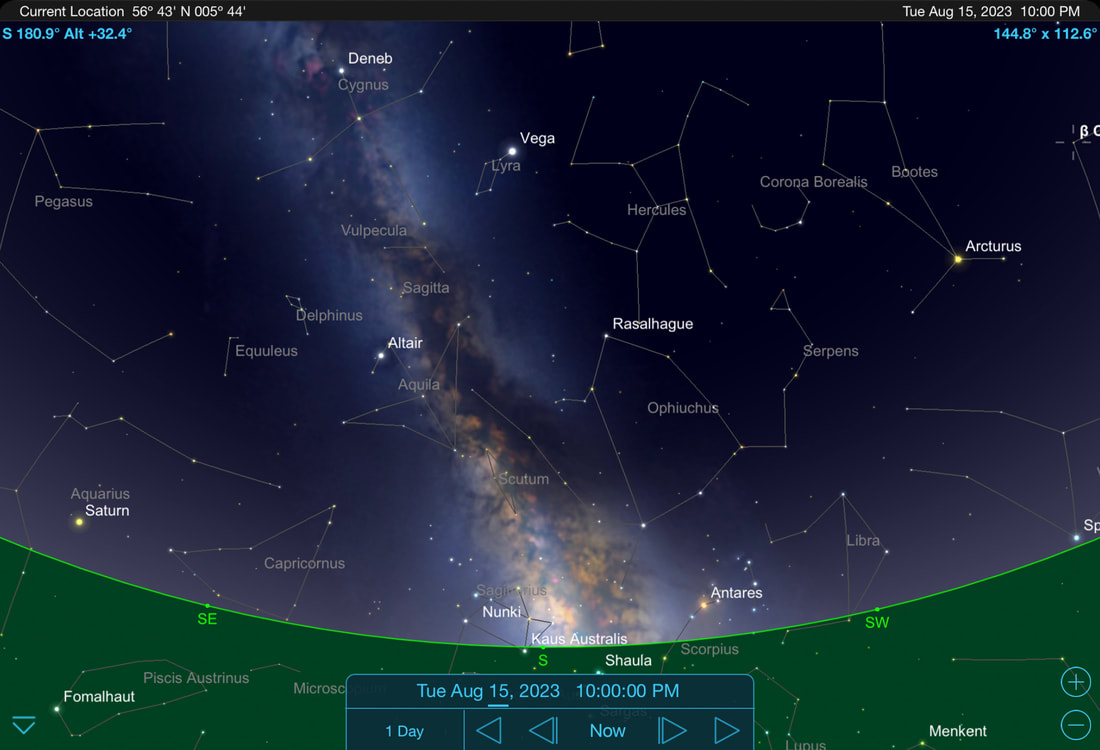

It’s now August and a few weeks since the Summer Solstice, so you should be noticing it getting dark earlier at night and the stars beginning to appear from about 10pm. Find out how to use the Summer Triangle to navigate your way around them and to also find the cloudy core of the Milky Way. Also find out the best times to look for the two full Supermoons we have this month and for when to watch for shooting stars from the Perseid Meteor shower. The ConstellationsWith sunset now at around 9:00 pm, the stars and the constellations will become visible from about 10:00 pm onwards. As with July, the best way to navigate your way around the night sky is to use the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb. Start off by finding Vega, a bright white star which will be directly overhead. Next is Altair, which you will find halfway between Vega and the southern horizon. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and across from Vega. Once you have found the Summer Triangle, you can now start to look for some constellations. There’s Cygnus the Swan, which is also known as the Northern Cross. It is a large cross-shape with Deneb at the top, marking the tail of a swan which flies down the Milky Way with outstretched wings towards Sagittarius (the Archer) which will be low down on the southern horizon. It’s not a particularly bright constellation, so you’ll need a good clear night and to be far away from any light pollution to see it. When you trace a line between these two constellations, you should be able to make out the Milky Way’s cloudy core, which is the dense and bright region at the centre of our galaxy and home to around 10 billion stars. It will be visible for about two hours after sunset, before dipping below the horizon at around midnight.

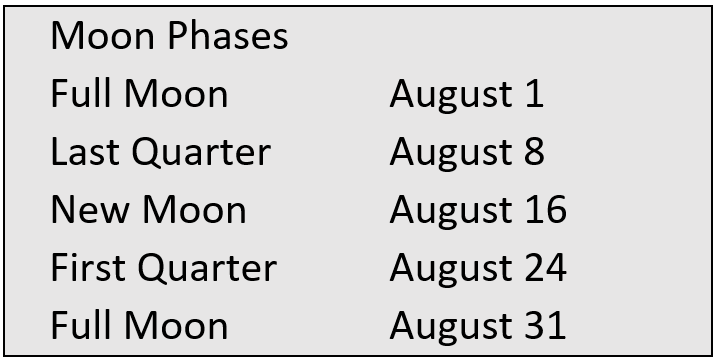

Although most of what to see is in the southern night sky, there are a few notable things to see if you look north. In the north-west, you will find the familiar shape of The Plough and you can use its two right hand stars to point towards Polaris (the Pole Star or North Star), which is always in the same position in the sky To the right of Polaris, you’ll see the W-shape of Cassiopeia, the constellation that represents the fabled vain queen of the same name. At this time of year her husband, king Cepheus, is high in the sky, though his stars are nothing like as bright as those of his beautiful wife. Below Cassiopeia are the stars of Perseus, after which the Perseid meteors are named. These meteors will peak on the night of 12-13 August, and you can find out more about them below. Finally, low down and below Perseus is Capella, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) and the sixth-brightest star in the night sky. The MoonWe start the month with the first of two full moons when the Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 7:31 pm on 1 August. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 31 July-1 August, 1-2 August, and 2-3 August. It will rise in the south-east at around 10:00 pm on 31 July, then at around at around 10:30 pm on 1 August and at around 10:45 pm on 2 August. Also, on the nights of 1-2 August and 2-3 August the Moon will be very close to Saturn. This full Moon will pass Earth near to the time it is closest to us in its elliptical orbit, making it a supermoon, or a Sturgeon Supermoon. It is the second of 4 supermoons we have this year with the others occurring on the following dates:

The last quarter Moon (a half-moon) is on 8 August. It will spend the night very close to Jupiter as it travels from east to west. The new Moon (no moon) is on 16 August. This means that a few of days before, on 14 and 15 August, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting in the north-east before sunrise. This will be from about 3:30 am to 4:30 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 18 and 19 August, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 24 August. You will find it in the southern western sky, sitting close to Antares and it sets at around 10:30 pm. Unusually, on the night of 30-31 August, a second full Moon, or Blue Moon, will make an appearance. This name does not refer to the Moon's colour, as the Moon usually appears in shades of grey or white. Instead, it refers when two full moons happen within a single calendar month, with the second being called a blue moon. This full Moon will also be a supermoon, making it a Blue Supermoon. It becomes 100% full at precisely 2:35 am on 31 August. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 30-31 August, 31 August-1 September, and 1-2 September. Rising in the east-south-east at around 9:00 pm on each of these three nights, it will be the closest, biggest, and brightest full supermoon of 2023 and a sight well worth looking for. The PlanetsSaturn is visible in the southern sky all night long this month and because it reaches its closest point to Earth on 27 August, it will be shining quite brightly. If you look at it through binoculars or telescope that magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune, which is also above the horizon all night long. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. Jupiter rises in the east at around 11:00 pm, shining brightly and dominating the night sky as it does so. If you look at it through binoculars, you’ll see its four largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons. Uranus will follow Jupiter, rising about quarter an hour later and may be just visible to the naked eye. Venus disappeared from the evening sky towards the end of last month and reappears in the dawn sky in the last week of this month. Rising at around 5:00 am, the Morning Star will be shining about twice as bright as Jupiter and will be the brightest thing in the night sky, apart for the Moon. Mercury and Mars are lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersAfter a few months’ absence, you’ll be able to see some shooting stars because the number of meteor showers is now on the increase. In fact, August can be a great month for spotting shooting stars because the peak of the annual Perseid Meteor Shower is on the 12-13 August. With the new Moon falling on 16 August, it should be a good year for seeing the Perseids because the Moon will only be a thin crescent and not too bright, so it won’t affect the show too much.

It is called the Perseid Meteor Shower because the radiant (the area of the sky where the meteors seem to originate) is located near the constellation of Perseus and although you can see them throughout the night, you will see more if you wait until this radiant is high in the night sky. This is usually from about midnight until dawn, so watch then to maximise your chances of spotting some shooting stars. Finally, when watching for shooting stars, give yourself at least an hour of observing time, because they will come in spurts, interspersed with lulls. Also remember that your eyes can take as long as 20 minutes to adapt to the darkness of night, so don’t rush the process. If you are patient, you may see up to 60 meteors per hour as the shower’s peak approaches.

0 Comments

It’s July and after the summer solstice, so the night sky is beginning to get dark again with the stars and the Milky Way becoming more and more visible as the days pass. You should be able to see its cloudy band of stars passing through Deneb and in between Vega and Altair, the three stars than make up the Summer Triangle. We have the first this year’s four supermoons with this month’s Buck Supermoon and Venus is reaches its brightest before disappearing from view in the second half of the month. Finally, you may be lucky enough to spot noctilucent clouds, ghostly whispers of light shimmering in the all-night twilight in the hours after sunset. The ConstellationsIt’s now after the Summer Solstice so it will begin to get dark at night again and with sunset at around 10:00 pm, you should see the constellations emerging from about 11:00 pm onwards. Also, at this time of year, we begin to see the Milky Way again and at the end of the month, this home to 200 billion stars will be visible from around 11:00 pm because it’s cloudy core will be above the southern horizon then.

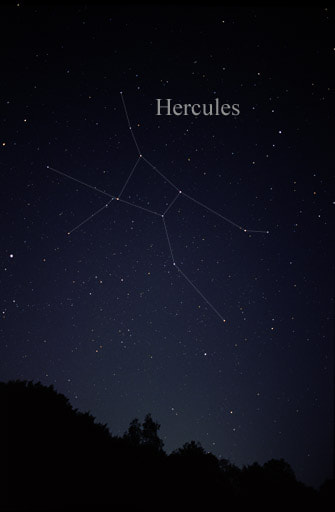

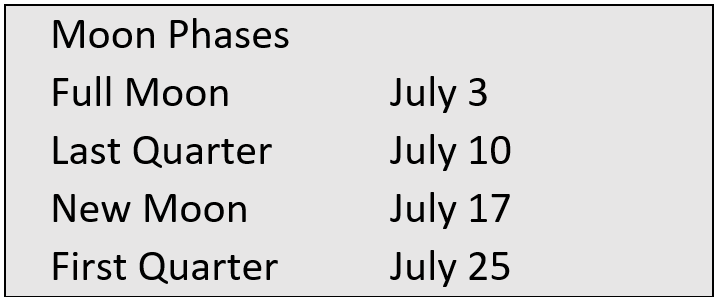

Above Ophiuchus, is the quadrilateral of stars known as the Keystone because of its wedged shape. This is the most recognisable part of the Constellation of Hercules, named after the Roman mythological figure who was known for his strength and numerous far-ranging adventures. The constellation is best known for its great globular cluster of stars, M13, and has a lesser globular cluster, M92, nearby. At one time, the globular cluster M13 was known as ‘The Great Hercules Cluster’. It is the brightest globular cluster in the northern hemisphere and is visible to both the naked eye and binoculars. It contains more than 300,000 stars and is 25,200 light-years from Earth. To find it, look about two thirds of the way up the right-hand side of the Keystone using a small telescope and you should see what looks like a circular misty patch. This is this is the star cluster and if you use a larger telescope, some of the individual stars will be visible. To the east of Scorpius, and just above the horizon, you will find the constellation Sagittarius (the Archer). This is not a particularly bright constellation, so you’ll need a clear night and be far away from any light pollution to see it. If you do spot the stars of Sagittarius, you will see that they form a sort of teapot shape. The handle of the teapot represents the upper body of the Archer, while the curve of three stars to the right are his bent elbow. The spout of the teapot is the point of an arrow which is aimed at Scorpius, the fearsome celestial scorpion. Sagittarius is rich in star clusters and nebulae, some of which you can see with binoculars on a night when the southern horizon is really clear. Above the spout of the teapot is the Lagoon Nebula, a giant interstellar cloud that’s visible to the naked eye. Near to it and visible with a telescope is the three-lobed Trifid Nebula, while above Sagittarius and in the Milky Way, you will find a bright patch of stars called the Sagittarius Star Cloud (M24). Above this, is the Omega Nebula, which is considered to be one of the brightest and most massive star-forming regions of our galaxy. Going back up to Vega, you’ll see the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre), of which Vega is the brightest star. Below Vega, you will see the constellation’s 4 other main stars, which form a small parallelogram. To its upper left is an interesting double star, Epsilon Lyrae. Some people can see this as a double star with the naked eye, but binoculars will show it well. If you use a telescope with an aperture larger than about 75 mm, you will be able to see that each of the two stars are themselves double stars. For this reason, some people refer to Epsilon Lyrae as the “Double Double”. The MoonWe start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes 100% full Moon at precisely 2:48 am on 3 July. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 1-2 July, 2-3 July, and 3-4 July. It will rise in the south-east at around 9:30 pm on 1 July when it will be close to Antares. After that, it will rise at around 10:45 pm on 2 July and at around after 11:30 pm on 3 July.

A full moon happens when the Moon (in its monthly orbit) is on the opposite side of Earth from the sun. A full supermoon happens when the full Moon happens at, or near to the time the Moon is closest to us in its elliptical orbit. To see what closest means, you can compare these Moon distances to the average Moon distance of 238,900 miles (384,472 km):

The new Moon (no moon) is on 17 July. This means that a few of days before, on 15 and 16 July, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting in the north-east before sunrise, which will be about 4:45 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 19 and 20 July, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. On these days, it will be close to Venus, Mercury, Regulus and Mars. The PlanetsVenus has been blazing away in the evening sky over the last few months and it reaches its maximum brightness on 9 July. It sets at around 11:15 pm, so look out for it before then if you want to see it. It will pass the Praesepe star cluster on 13 July and this sight will be well worth observing through binoculars or a telescope. As the nights pass, Venus will drop rapidly into the twilight glow and will have disappeared from view by the end of the month. At the beginning of the month, a considerably fainter Mars can be seen to the upper left of Venus. Over the past few months, the Evening Star and the Red Planet have been moving steadily closer together, being only 3.5 degrees apart in the first week of the July. However, as Venus drops towards the horizon, Mars is moving the other way, following a path beneath Leo before setting at around 11:00 pm. Mercury will appear to the lower right of Venus form about 15 July and will move upwards towards Mars as the month progresses, becoming easier to see as it does so. Look out for it before it sets at around 10:00 pm. While Mars, Mercury and Venus are setting over in the west, take a look over to the east and you will see Saturn rising at about 11:00 pm and spends the night crossing the southern sky in the constellation of Aquarius. It will be shining reasonably brightly, so you should be able to make it out when it is just above the Moon on the night of 6-7 July. Neptune will rise in the east at about 0:30 am, while Jupiter will be clearing the horizon at about 1:30 am. This giant planet will be shining very brightly just beneath the constellations of Aries and Triangulum, and it will be very close to the Moon on the morning of 12 July. Uranus will follow Jupiter, rising about half an hour later at 2:00 am and may be just visible with the naked eye. Meteor ShowersJuly sees the number of meteors increasing and it may be possible to spot some shooting stars from the alpha Capricornid and the delta Aquarid meteor showers. They peak around 30 July, just two days before a full Moon, so viewing conditions will be poor and only the brightest meteors might be visible. Dark, moonless skies are always best for seeing meteors. It will be best to wait until the Perseid Meteor Shower in August for our next good show. Radiating from the constellation of Perseus, it will be active between 17 July and 24 August and will peak on the night of 12-13 August. With the new Moon falling on 16 August, it should be a good year for seeing them because the Moon will only be a thin crescent and not too bright, so it won’t affect the show too much. If you do want to look for the Perseids, then they will be at their best on the few hours before dawn on 14 August when the radiant point is at its highest in the sky. Noctilucent CloudsIn the 8 or so weeks either side of the Summer Solstice, which was on 21 June, the Sun gets to no more than 10-15 degrees below the horizon and full darkness does not occur at any point during the night. During this time you may be lucky enough to spot noctilucent, or “night-shining” clouds.

These clouds become visible in the north to north-west sky as darkness falls and just as the brightest stars become visible. They have the appearance of ghostly whispers of light shimmering in the all-night twilight and are usually set against a pearly-blue sky. Forming in the middle atmosphere, or mesosphere, roughly 80 kilometres (50 miles) above Earth's surface, they are thought to be made of ice crystals that form on fine dust particles from meteors and volcanic activity. These ice coated dust particles then reflect the light that the sun projects high up into the sky, when it is between 6 to 16 degrees below the horizon, to create an illuminated cloudy veil in the northern sky at latitudes between ±50° and ±70°. They are first known to have been observed in 1885, two years after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, but it remains unclear as to whether their appearance had anything to do with the volcanic eruption or whether their discovery was due to more people observing the spectacular sunsets caused by the volcanic debris in the atmosphere. |

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved