|

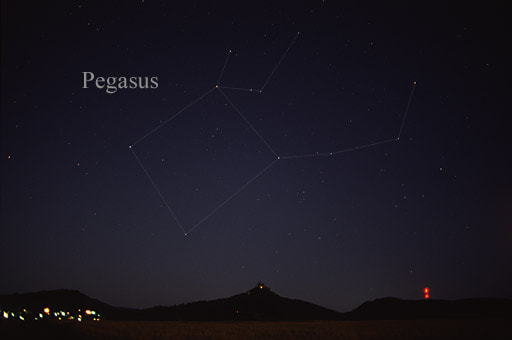

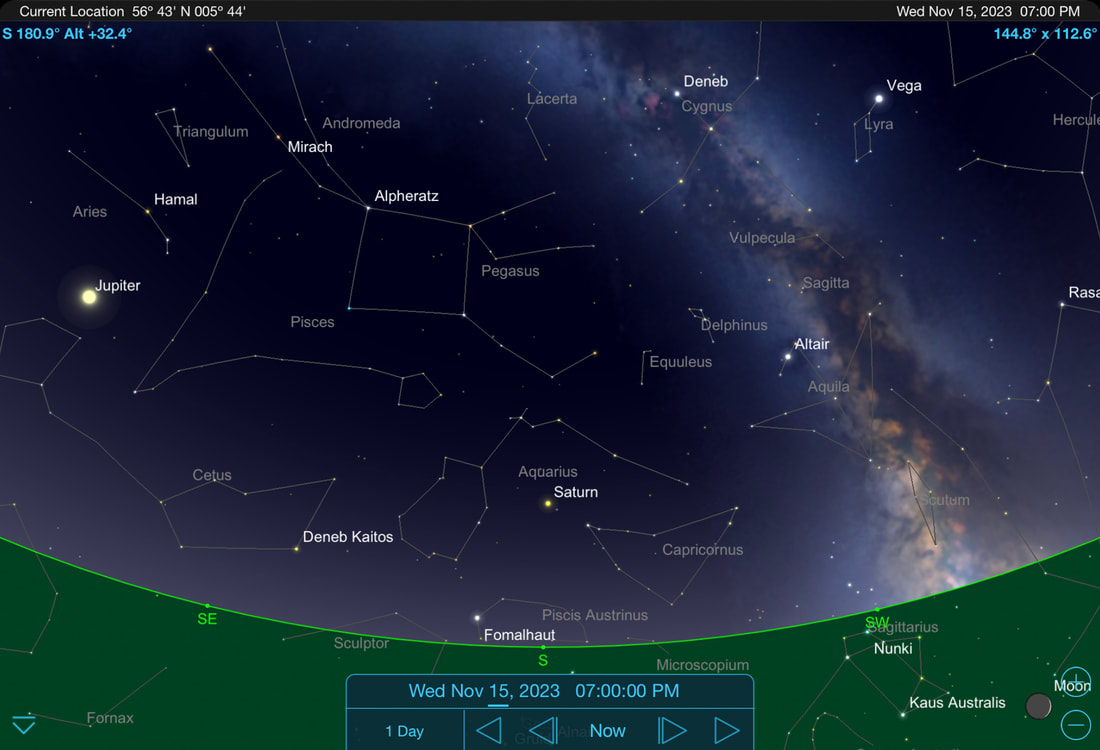

The clocks have changed, and the Sun now sets not long after 4:00 pm to give us long dark nights for stargazing. The Great Square of Pegasus is now in the southern sky and available for us to use to find our way around the many constellations that surround it. Both Jupiter and Venus are shining bright, with Jupiter being at its brightness this month, giving us the opportunity for some great planet watching. Finally, you may be able to spot shooting stars produced as a steady stream from the Taurid meteor showers in the first part of the month, followed by a second opportunity to spot some more when the Leonids meteor shower peaks on 17 November. The ConstellationsFollowing the clock change at end of last month, the sun now sets not long after 4:00 pm, meaning that the stars and constellations start to become visible from about 5:30 pm onwards. During the previous three months we have been watching the Milky Way get lower and lower in the southern night sky and you may have noticed the constellations in the south getting dimmer. This is because the position of the Earth is now such that we are looking out of the plane of our galaxy and into the rest of the universe. The Milky Way has not gone altogether, and you can see it over in the west along with the Summer Triangle of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb, which we have been using to navigate our way around the night sky in previous months. However, it is now better to use the Great Square of Pegasus, a large square asterism made up of 4 stars of nearly equal brightness which you can find high up in the southern night sky. The four stars are Scheat, Alpheratz, Markab and Algenib and you will need to look carefully to find them as they are all of second magnitude, so they aren’t the brightest.

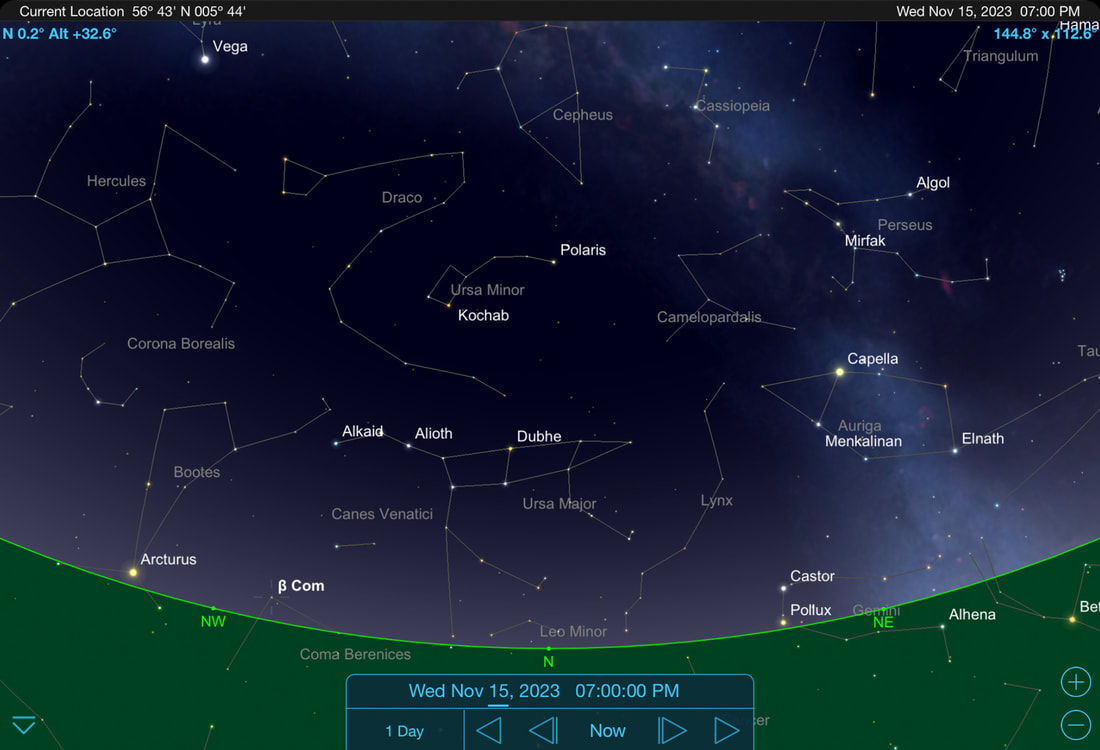

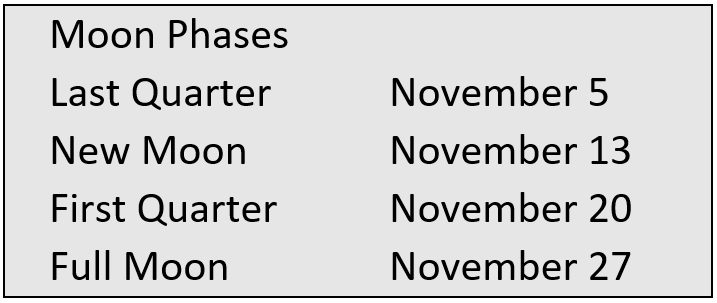

If you follow the diagonal down from the top left of the Square to beyond its bottom right star, you’ll come to a faint group of stars known as the Water Jar of Aquarius. It is an asterism formed by four relatively bright stars in the constellation of Aquarius (the Water-Carrier). It is easily recognised by its arrow shape, which looks a bit like a fighter plane with swept wings. Though it’s not the brightest part of Aquarius, it’s a good pattern that helps you to find its other stars. A line of stars in the constellation of Andromeda stretches from the top left edge of the Square a constellation that is named after the daughter of Cassiopeia who, in the Greek myth, was chained to a rock to be eaten by the sea monster Cetus but was saved from death by Perseus. The constellation is the home of the Andromeda Galaxy which, at approximately 2.5 million light-years from Earth, is the nearest spiral galaxy to our own galaxy, the Milky Way. It is also the most distant object that you are likely to see without an optical aid. However, if you can’t find it with the naked eye, use binoculars to look for a little oval blur. Below Andromeda and to the left of Pegasus is where you will find the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). It is very faint and difficult to see, so the best way to find it is to look directly below the Square of Pegasus for the Circlet of Pisces, which is a pentagonal asterism of 5 stars that marks the head of the Western Fish. Once you’ve found it, go on from there to catch the Eastern Fish which is jumping upward to the east of the Square of Pegasus. The entire constellation looks like the letter V. Below Pisces is the constellation of Cetus, the Sea Monster which in Greek mythology both Perseus and Heracles needed to slay. You’ll find its tail marked by a fairly bright star called Diphda located low down in the sky, which is almost directly below the left-hand edge of the Square of Pegasus, while further over to the left and up a little, you’ll find Menkar, a reasonably bright star that marks its head. You may have noticed that all the constellations in this part of the sky have watery connections. It is said that this is because the Sun travelled through these constellations during the wet season in ancient Mesopotamia, which was from November to March, and flooding was a major problem. The naming of many of our constellations dates from that location and time. Finally, to the east of the Square is Aries, the Ram, whose three main stars form an easily recognised triangle. You’ll find another more regular triangle close to this one which is actually called Tringulum, the Triangle. It contains the nearby galaxy M33, which will be visible with binoculars if you have a reasonably dark sky. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, except that their orientation varies. This month the familiar Plough asterism, which many people will recognise, is low down in the north just now, with its rectangular end almost directly below Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. It is a yellow giant star, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer), the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, and the third brightest in the northern celestial hemisphere after Arcturus and Vega. The MoonThere was a full Moon on 28 October, so we start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 5 November. The new Moon (no moon) is on 13 November and a few days before that, on 9 November, you can see a crescent Moon sitting very close to a bright shining Venus over in the southeast from 3:00 am until the sun rises at just before 8:00 am. You should also be able to see a crescent Moon at daybreak on 10 and 11 November, but it will be too close to the Sun on 12 October to be visible. Alternatively, a few days later, on 16 and 17 November, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the southern sky as the Sun sets. The Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 9:16 am on 27 November. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 26-27 November, 27-28 November, and 28-29 November. It will rise in the northeast at around 3:00 pm on 26 November, at about 3:20 pm on 27 November and at about 3:50 pm on 28 November. This month’s full Moon is called the Beaver Moon. There is disagreement over the origin this name with some saying that it comes from Native Americans setting beaver traps during this month, while others say it comes from the heavy activity of beavers building their winter dams. It is also known as the Frosty Moon, and along with December’s Full Moon, some called it the Oak Moon. Traditionally, if the Beaver Moon is the last Full Moon before the winter solstice, it is also called the Mourning Moon. The PlanetsAs darkness falls, you will see Saturn sitting above the south-eastern horizon. It will be visible until it sets at around 11:30 pm and if your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own Moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out on the border between Aquarius and Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. It sets at about 2:00 am. Next to see is Jupiter, rising well over in the east at around 4:00 pm. It is at its closest to Earth on 1 November at 370 million miles away. Two days later it’s at opposition, when it is in line with the Sun and Earth and it will be shining at its brightness as a result. If you look at it through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. If you use a telescope, you will be able to see its roiling clouds and the huge storm know as the Great Red Spot. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about 10-15 minutes later. You may be able to spot it with the naked eye but will stand a much better chance of seeing it if you use binoculars or a telescope. In fact, a telescope should reveal its disc and its largest moons. Next up is Venus, rising in the eastern sky at around 3:00 am and continuing to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky except for the Moon. Mercury and Mars are too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersDuring the first part of the month, the South and North Taurid meteor showers are very noticeable. Unlike other meteor showers, they don’t have strong peaks but instead have “staying power” and produce a steady stream of meteors over a number of weeks. The South Taurids are active from about 10 September to 20 November, while the North Taurids are active from about 20 October to 10 December.

These showers produce about 5 meteors/hour each and because they overlap up until 20 November, you can expect to see up to 10 meteors/hour during the first 2-3 weeks of the month. However, the best nights to look for them will be during the few nights either side of the new Moon on 13 November because there will be little or no moonlight to drown them out. The showers’ radiant points, the part of the sky from which the meteors originate, rise in early evening and are at their highest in the sky around midnight, so this will be the best time on these nights to look for them. We also have the Leonid meteor shower this month and it is known for periodic storms of historic proportions, when shooting stars fall like rain. While no storm is predicted for the 2023 Leonids, you can still catch plenty of meteors between 3 November and 2 December. This meteor shower peaks the morning of 17 November. This is only a few days after a new Moon, giving us a near moonless night, meaning that it is a good year to look for them. The shower’s radiant rises around midnight, so the best time to look for them will be from then until dawn on 18 November.

0 Comments

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved