|

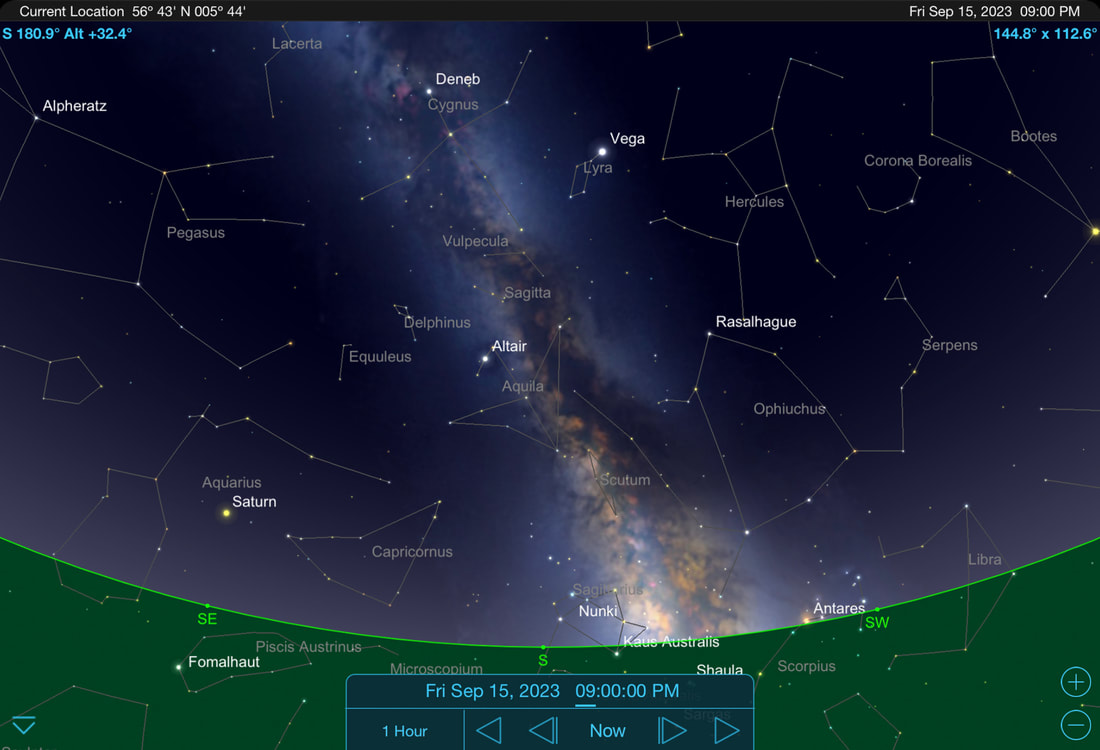

Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and when the sun is directly above the earth’s equator. On that date, day and night are of equal length and the Sun rises due east and sets due west. With this, the dark nights return and, because it doesn’t get too cold outside, September is a great month for stargazing. According to NASA, the Equinox is a prime time for Northern Lights so, if you want to catch a glimpse of them, do keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on social media. The ConstellationsThis month the sun sets around 8:00 pm and the stars and the constellations become visible from about 9:00 pm onwards. As with July and August, the best way to navigate your way around the night sky is to use the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb. Start off by finding Vega, a really bright white star, which will be directly overhead. Next is Altair, which you will find halfway between Vega and the southern horizon. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and across from Vega. Once you have found the Summer Triangle, you can start to look for some of the constellations in the southern sky. Start off with Vega, the constellation of Lyra’s (the Lyre) brightest star. Below it, you will see the constellation’s four other main stars. These form a small parallelogram and make up the body of the Lyre – the sky’s only musical instrument.

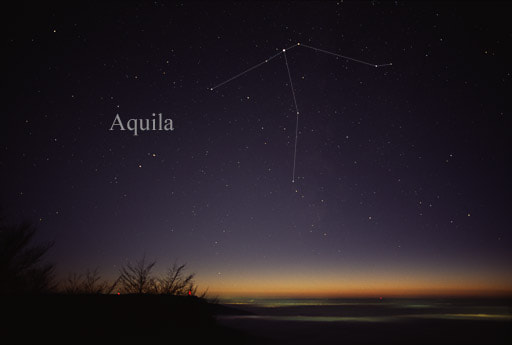

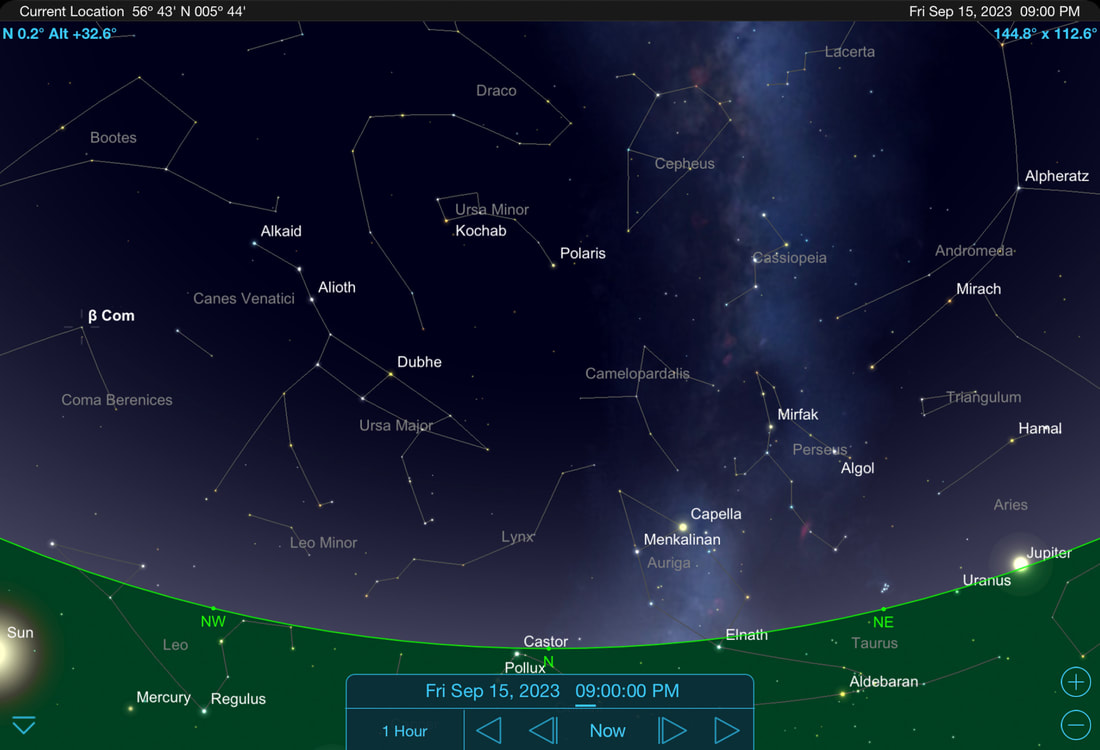

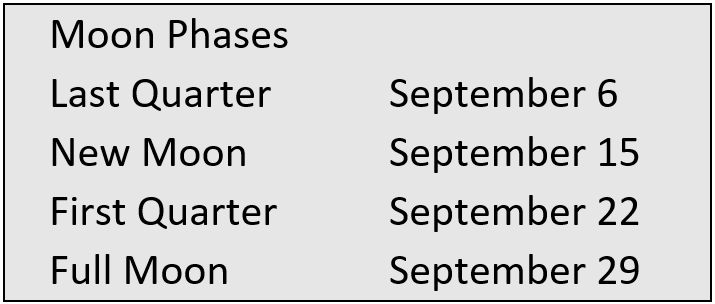

Finally, looking at Altair, which you will find the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) because Altair is its brightest star. Altair also has outstretched wings, though they are not as obvious at the wings of Cygnus, and in Greek mythology, Aquila is identified as the eagle that carried Zeus’ thunderbolts and was once dispatched by the god to carry Ganymede, the young Trojan boy Zeus desired, to Olympus to be the cup bearer of the gods. In between these two flying birds is the constellation of Sagitta (the Arrow), a dim but distinctive shape which is reasonably easy to pick out. Another small but easily seen constellation called Delphinus (the Dolphin) is nearby and it also looks like what it’s meant to be. The two better-known constellations of Capricornus and Aquarius are below Delphinus in the lower part of the sky. They are well known because they are in the Zodiac, the path of the planets but, as they have no very bright stars, you might not be able to pick them out. Capricornus is the Water-Goat and Aquarius is a human, the Water-Carrier. As with August, September is a good month to view the Milky Way. If you trace a line down from Deneb and through Altair, you should be able to make out the Milky Way’s cloudy core well to the right of Saturn, which you’ll find shining bright low down in the south to south-east sky. The cloudy core will be visible up until about 10:00 pm. When you look at the Milky Way, you’ll notice a black band running down it’s middle, between the stars. William Herschel, the first astronomer to map our Galaxy, thought that this was a hole in space, but it is actually a dark swathe of sooty dust, known as the Great Rift in Cygnus, which runs along the disc of our Galaxy. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. By September the familiar Plough asterism, which many people recognise, is down over to the north-west. Follow its two right-hand stars upward, veer a little bit to the right and you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. Contrast its colour with that of Vega, which is virtually overhead at this time of year. Capella is a yellow giant star, while Vega is a slightly bluer star than the Sun. The contrast is obvious if you look from one to the other. The MoonThere was a Blue Supermoon on 31 August, so we start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 6 September, after passing close by Jupiter over in the east, on 4 September. Meanwhile, if you look just above the Moon on 5 September, you should be able to spot the glimmering Pleiades star cluster, a lovely sight through a pair of binoculars.

We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 22 September. You will find it in the southern sky in the hour or so after sunset before it sets at around 9:30 pm. Then, a few days later, on 26 September the Moon will be over in the south-east and very close to Saturn. The Moon then becomes 100% full at precisely 10:57 am on 29 September. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 28-29 September, 29-30 September, and 30 September-1 October. It will rise in the east at around 7:00 pm on 28 September, at around 7:15 pm on 29 September and then at around 7:30 pm on 30 September. September’s full moon is called the Corn Moon because this is when crops are gathered at the end of the summer season. At this time of year, the Moon appears particularly bright and rises early, thus letting farmers continue harvesting into the night. This Moon is also sometimes named the Barley Moon and, like this year, it is often the nearest full moon to the autumnal equinox, earning it the title of 'Harvest Moon'. The PlanetsThis month, the first planet you will see is Saturn, which will be sitting above the south-eastern horizon as darkness falls. If your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. Next to see is Jupiter, rising over in the east at around 9:00 pm. If you look at Jupiter through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about quarter an hour later and may only be visible through binoculars or a telescope. Finally, rising in the eastern sky at around 3:30 am, Venus continues to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky, apart from the Moon. From about 20 September, Mercury will rise in the east at around 5:00 am, sitting well to the lower left of Venus. It’s at its maximum separation from the Sun on 22 September. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersThe annual Perseid Meteor Shower peaked last month and those of you who were lucky enough to have clear skies around its peak on the night of 12-13 August may have seen some of the brighter meteors shooting across the sky. However, September is not a good month for meteor showers, so we will have to wait until October for the chance to see some more. The Draconids are expected to peak at nightfall on 8 October and the Orionids are expected to peak between midnight and dawn on the night of 21-22 October. Autumnal Equinox & Northern LightsThe Autumnal Equinox is when night and day are nearly exactly the same length (12 hours). It also marks the start of astronomical autumn and when the nights start to become longer than the days. Although the autumnal equinox referred to as a day by many people, it’s actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the Sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the Sun. For 2023, this will be at 7:50 am on Saturday 23 September.

The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Finally, if you do want to catch a glimpse of the “Merry Dancers”, be sure to keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on the web and on social media. Good sources for forecast and alerts are AuroraWatch UK, Glendale Skye Auroras and Aurora Research Scotland.

0 Comments

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved