|

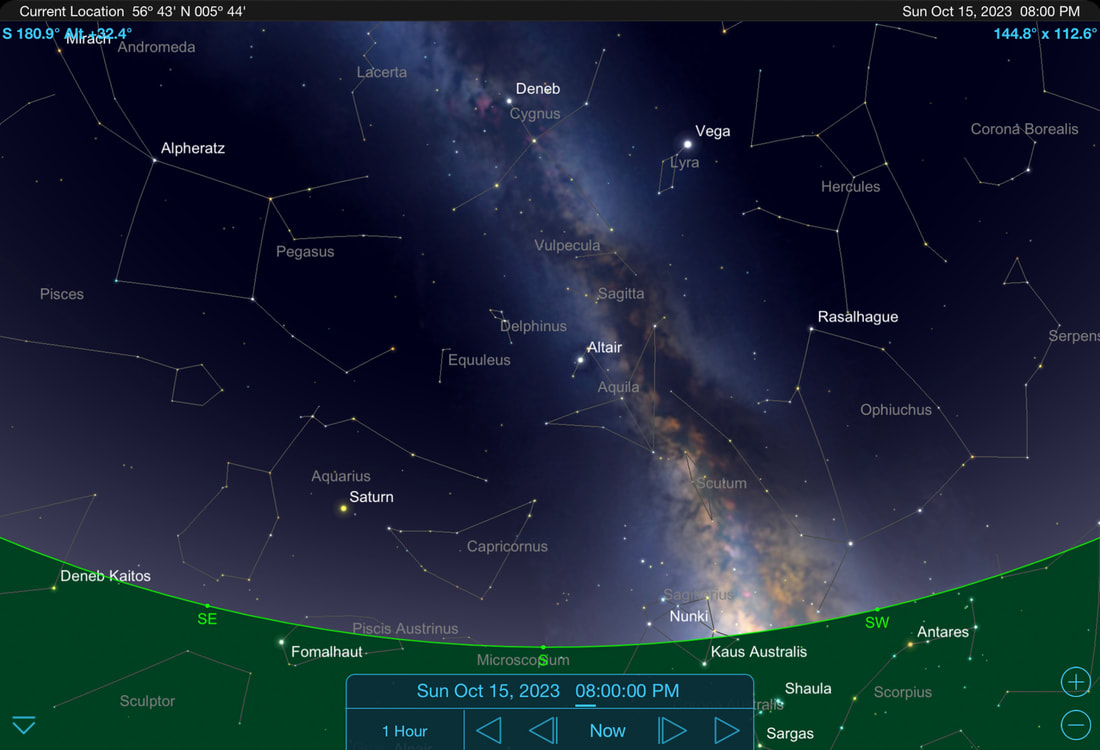

We had the Autumnal Equinox at the end of last month and with it comes ever shorter days and longer nights, making it ideal for stargazing. Although there are not too many bright stars in the lower half of the sky, there is much to see higher up, with the Great Square of Pegasus entering our southern night sky. There’s also a chance of seeing some shooting stars, with the peak of the Draconids Meteor Shower on the night of 8/9 October and the peak of the Orionids meteor shower on the night of 21/22 October. Finally, there will be a partial lunar eclipse visible to us here in the UK on the night of 28th October. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 6:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 8:00 pm onwards. Even though we are now into Autumn, the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb, is still visible and can be used to navigate your way around the night sky. Start off by finding Vega, a really bright white star which will be high up in the sky to the South-West. Just face south, look up, then look right and you will find it. Next is Altair, which you will find below Vega, halfway down towards the horizon and slightly to the left. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and above and to the left of Vega. The Milky Way, which has dominated the night sky over the last couple of months can still be seen during the early part of the night. Just trace a line down from Deneb, through Altair and you should be able to make out its band of stars as it flows down to the horizon, with the last of its cloudy core visible and well over to the right of Saturn as it sits above the southern horizon. At the moment there are not many bright stars in the lower part of the southern sky so, if you are in an area with light-pollution, look higher up and you should be able to pick out some constellations. Below Vega, you will see the 4 other main stars that make up the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). These form a small parallelogram and make up the body of the Lyre – the sky’s only musical instrument.

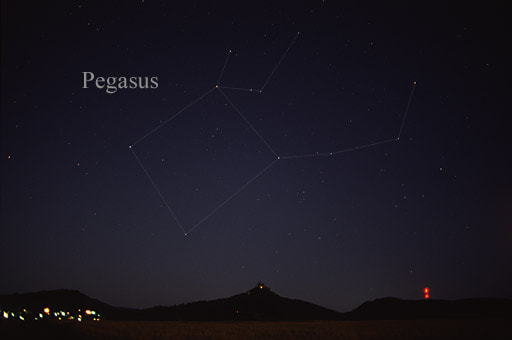

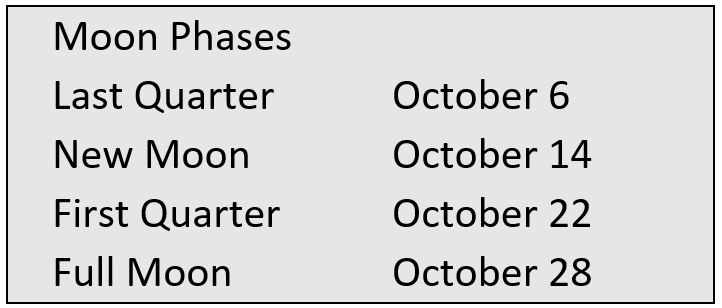

Finally, looking at Altair, you will find the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) because Altair is its brightest star. Altair also has outstretched wings, though they are not as obvious at the wings of Cygnus. In between these two flying birds is the constellation of Sagitta (the Arrow), a dim but distinctive shape which is reasonably easy to pick out. Another small but easily seen constellation called Delphinus (the Dolphin) is nearby and it also looks like what it’s meant to be. If you look high up and over to the South-East, you’ll find the Square of Pegasus sitting above the halfway point between Saturn and a bright shining Jupiter. This asterism is made up of 4 stars of nearly equal brightness in a large square pattern and the stars are Scheat, Alpheratz, Markab and Algenib. The constellation of Pegasus represents the Flying Horse of Greek mythology and the Square marks the horse’s body. You may find it difficult to make out the horse because it is upside down and the constellation represents only the top half of its body and its head. However, you may be able to pick out Enif, the constellation’s brightest star which will be about halfway between the bottom right of the Square and Altair. Enif is an orange supergiant star that is 5,000 times brighter than the Sun and it represents the horse’s nose. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. In October the familiar Plough asterism, which many people will recognise, is moving from the north-west to the north. Follow its two right-hand stars upward, veer a little bit to the right and you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. It is a yellow giant star, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer), the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, and the third-brightest in the northern celestial hemisphere after Arcturus and Vega. The MoonThere was a Supermoon on 29 September, so we start the month with an almost full Moon. On 1 October, it very close to Jupiter, over in the eastern sky. It becomes a last quarter Moon on 6 October and on that night, you can find it near Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini.

We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 22 October. You will see it in the southern sky as darkness falls and it will remain visible until it sets at 11:30 pm. Then, on 23 and 24 October, you will find it a bit further over to the south-east and close to Saturn as darkness falls. Next, the Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 9:24 pm on 28 October. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 27-28 October, 28-29 October, and 29-30 October. It will rise in the east at around 5:30 pm on 27 October and at about 10 minutes later on 28 October. It will rise just over an hour later on 29 October, at around 4:45 pm, with the jump of an hour being due to the clocks changing from British Summer Time to Greenwich Mean Time on that day. As well as there being a full Moon on 28 October, there will also be a partial lunar eclipse. It will be visible from the UK, beginning at 8:35 pm and ending at 9:53 pm. So if the sky is clear, look out for it and you will see part of the Moon being clipped by Earth’s dark umbral shadow. This month’s full Moon is called the Hunter’s Moon because traditionally, people in the Northern Hemisphere spent the month of October preparing for the coming winter by hunting, slaughtering, and preserving meats for use as food. Like the last month’s Harvest Moon, the Hunter's Moon is also particularly bright and long in the sky, giving hunters the opportunity to stalk prey at night. Other names include the travel moon and the dying grass moon. The PlanetsThis month, the first planet you will see is Saturn, which will be sitting above the south-eastern horizon as darkness falls. It will be visible until it sets at around 2:30 am and if your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own Moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. It sets at about 5:00 am. Next to see is Jupiter, rising over in the east at around 7:00 pm. If you look at Jupiter through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about 5-10 minutes later and may only be visible through binoculars or a telescope. Next, rising in the eastern at around 3:15 am, is Venus continuing to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky with the exception of the Moon. For the first few mornings of October, you may be able to catch Mercury very low down on the eastern horizon as it rises in the east at around 5:00 am. However, after only a few days it will drop down into the pre-dawn glow and disappear from sight. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersThe Orionid meteors fly each year between about October 2 to November 7 and are caused by debris from Halley’s Comet smashing into the Earth’s atmosphere. You can spot them from the start of the month, but you can see the greatest number at the meteor shower’s peak on the night of 21-22 October.

In a good year, with little or no Moon, you can expect to see about 10-20 meteors/hour at the peak. This will be the case this year because the first quarter Moon will set at around midnight and therefore not interfere with the best viewing time of around 2:00 am, This is when the meteor shower’s radiant point (the area of the sky where the meteors seem to originate) is highest in the sky and you will find it to the top left of Orion as it rises in the east. Instead of the Orionids, you could watch for the Draconid meteors from nightfall on October 8, right through to the wee hours of the morning of 9 October. It is an unusual meteor shower because its radiant point stands highest in the sky as darkness falls and this year, this means that the waning crescent Moon (23% illuminated) which doesn’t rise until about 1:00 am, will not interfere with the show. If you do decide to look, you’ll find the radiant point a little bit to the right of Vega and right next to the head of the constellation Draco the Dragon. Also, the Draconids meteor shower is known as “a Sleeper” because in most years it produces only a handful of meteors per hour. However, do look out for them because the Draconids’ unpredictable nature, as seen in both 1933 and 1946, means that you could enjoy thousands of meteors in only one hour. Finally, when watching for the meteors, give yourself at least an hour of observing time, because they will come in spurts, interspersed with lulls. Also remember that your eyes can take as long as 20 minutes to adapt to the darkness of night, so don’t rush the process. Patience is the key to maximising your chances of spotting some.

4 Comments

|