|

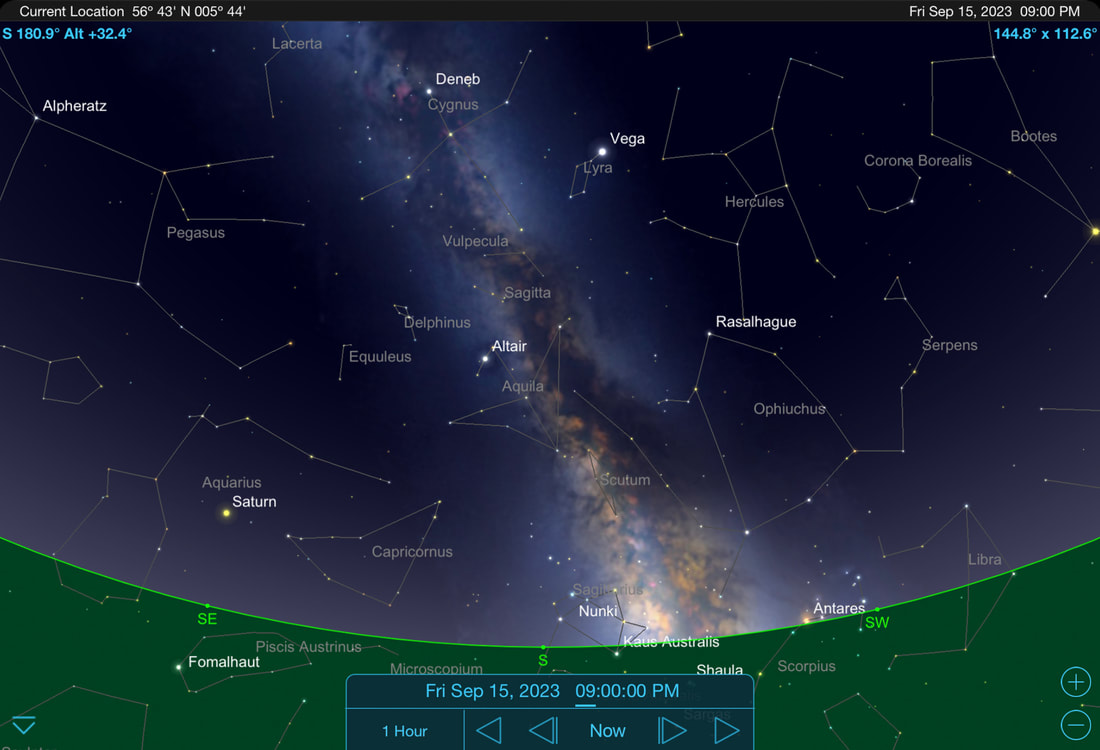

Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and when the sun is directly above the earth’s equator. On that date, day and night are of equal length and the Sun rises due east and sets due west. With this, the dark nights return and, because it doesn’t get too cold outside, September is a great month for stargazing. According to NASA, the Equinox is a prime time for Northern Lights so, if you want to catch a glimpse of them, do keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on social media. The ConstellationsThis month the sun sets around 8:00 pm and the stars and the constellations become visible from about 9:00 pm onwards. As with July and August, the best way to navigate your way around the night sky is to use the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb. Start off by finding Vega, a really bright white star, which will be directly overhead. Next is Altair, which you will find halfway between Vega and the southern horizon. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and across from Vega. Once you have found the Summer Triangle, you can start to look for some of the constellations in the southern sky. Start off with Vega, the constellation of Lyra’s (the Lyre) brightest star. Below it, you will see the constellation’s four other main stars. These form a small parallelogram and make up the body of the Lyre – the sky’s only musical instrument.

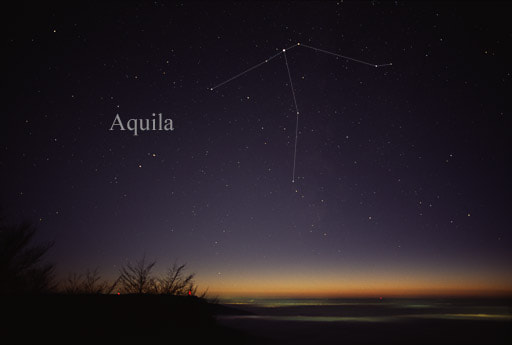

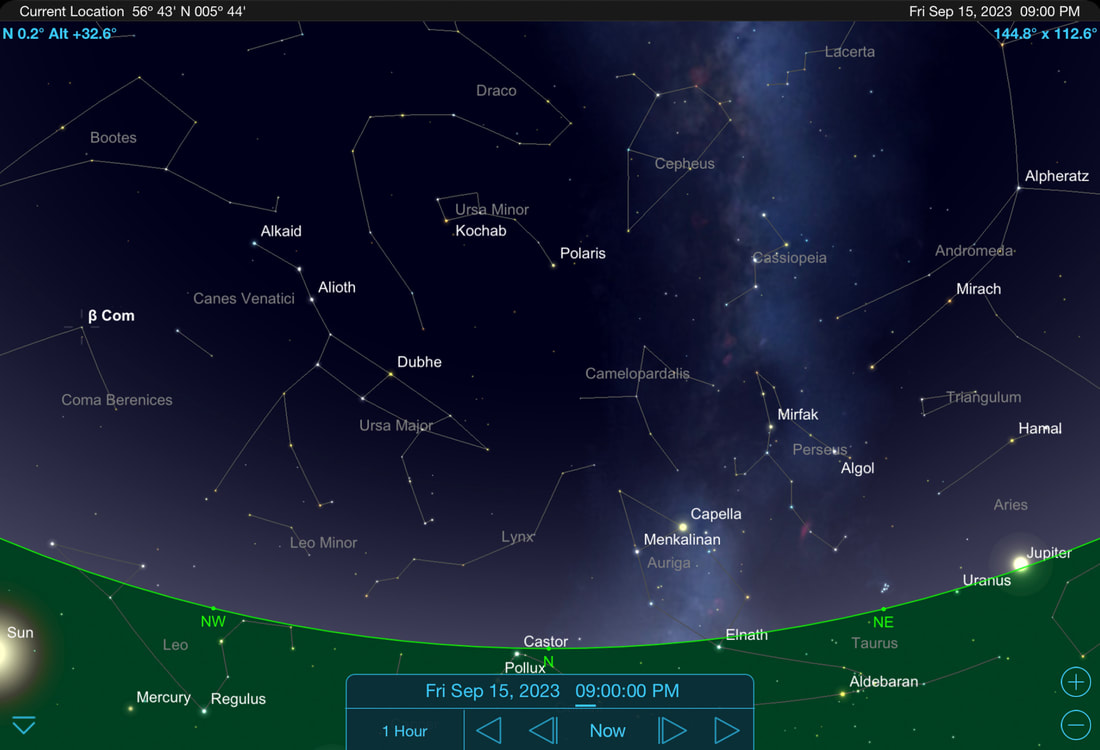

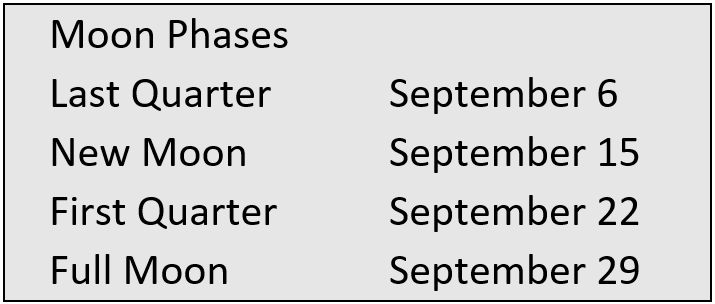

Finally, looking at Altair, which you will find the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) because Altair is its brightest star. Altair also has outstretched wings, though they are not as obvious at the wings of Cygnus, and in Greek mythology, Aquila is identified as the eagle that carried Zeus’ thunderbolts and was once dispatched by the god to carry Ganymede, the young Trojan boy Zeus desired, to Olympus to be the cup bearer of the gods. In between these two flying birds is the constellation of Sagitta (the Arrow), a dim but distinctive shape which is reasonably easy to pick out. Another small but easily seen constellation called Delphinus (the Dolphin) is nearby and it also looks like what it’s meant to be. The two better-known constellations of Capricornus and Aquarius are below Delphinus in the lower part of the sky. They are well known because they are in the Zodiac, the path of the planets but, as they have no very bright stars, you might not be able to pick them out. Capricornus is the Water-Goat and Aquarius is a human, the Water-Carrier. As with August, September is a good month to view the Milky Way. If you trace a line down from Deneb and through Altair, you should be able to make out the Milky Way’s cloudy core well to the right of Saturn, which you’ll find shining bright low down in the south to south-east sky. The cloudy core will be visible up until about 10:00 pm. When you look at the Milky Way, you’ll notice a black band running down it’s middle, between the stars. William Herschel, the first astronomer to map our Galaxy, thought that this was a hole in space, but it is actually a dark swathe of sooty dust, known as the Great Rift in Cygnus, which runs along the disc of our Galaxy. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. By September the familiar Plough asterism, which many people recognise, is down over to the north-west. Follow its two right-hand stars upward, veer a little bit to the right and you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. Contrast its colour with that of Vega, which is virtually overhead at this time of year. Capella is a yellow giant star, while Vega is a slightly bluer star than the Sun. The contrast is obvious if you look from one to the other. The MoonThere was a Blue Supermoon on 31 August, so we start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 6 September, after passing close by Jupiter over in the east, on 4 September. Meanwhile, if you look just above the Moon on 5 September, you should be able to spot the glimmering Pleiades star cluster, a lovely sight through a pair of binoculars.

We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 22 September. You will find it in the southern sky in the hour or so after sunset before it sets at around 9:30 pm. Then, a few days later, on 26 September the Moon will be over in the south-east and very close to Saturn. The Moon then becomes 100% full at precisely 10:57 am on 29 September. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 28-29 September, 29-30 September, and 30 September-1 October. It will rise in the east at around 7:00 pm on 28 September, at around 7:15 pm on 29 September and then at around 7:30 pm on 30 September. September’s full moon is called the Corn Moon because this is when crops are gathered at the end of the summer season. At this time of year, the Moon appears particularly bright and rises early, thus letting farmers continue harvesting into the night. This Moon is also sometimes named the Barley Moon and, like this year, it is often the nearest full moon to the autumnal equinox, earning it the title of 'Harvest Moon'. The PlanetsThis month, the first planet you will see is Saturn, which will be sitting above the south-eastern horizon as darkness falls. If your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. Next to see is Jupiter, rising over in the east at around 9:00 pm. If you look at Jupiter through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about quarter an hour later and may only be visible through binoculars or a telescope. Finally, rising in the eastern sky at around 3:30 am, Venus continues to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky, apart from the Moon. From about 20 September, Mercury will rise in the east at around 5:00 am, sitting well to the lower left of Venus. It’s at its maximum separation from the Sun on 22 September. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersThe annual Perseid Meteor Shower peaked last month and those of you who were lucky enough to have clear skies around its peak on the night of 12-13 August may have seen some of the brighter meteors shooting across the sky. However, September is not a good month for meteor showers, so we will have to wait until October for the chance to see some more. The Draconids are expected to peak at nightfall on 8 October and the Orionids are expected to peak between midnight and dawn on the night of 21-22 October. Autumnal Equinox & Northern LightsThe Autumnal Equinox is when night and day are nearly exactly the same length (12 hours). It also marks the start of astronomical autumn and when the nights start to become longer than the days. Although the autumnal equinox referred to as a day by many people, it’s actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the Sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the Sun. For 2023, this will be at 7:50 am on Saturday 23 September.

The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Finally, if you do want to catch a glimpse of the “Merry Dancers”, be sure to keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on the web and on social media. Good sources for forecast and alerts are AuroraWatch UK, Glendale Skye Auroras and Aurora Research Scotland.

0 Comments

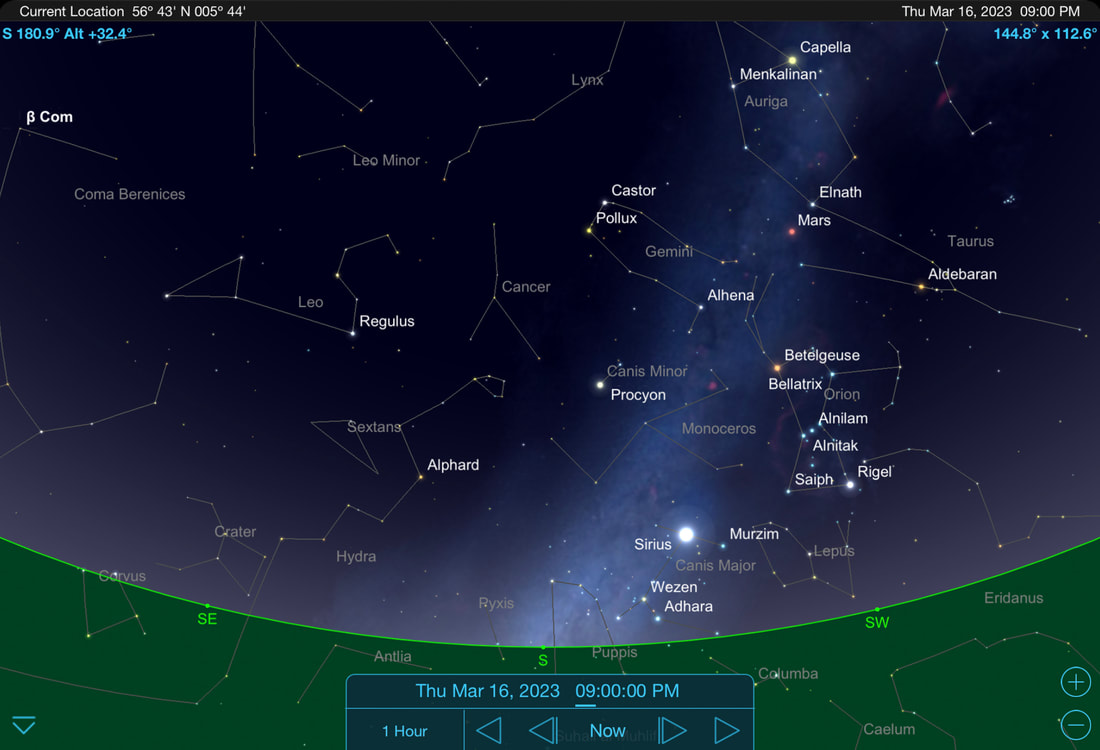

Spring arrives this month, with the Spring Equinox occurring on 20 March. On that day, the Sun rises at about 6:25 am due east and sets at about 6:25 pm due west. From then on, the nights get shorter and the days get longer. British Summer Time (Daylight Saving Time) starts on 26 March, so it gets dark a lot later in the evening. However, don’t be put off by the nights becoming shorter because there is still much to see, with the bright winter constellations still being visible and the constellation of Leo (The Lion) coming in to view. Also, it’s a great time of the year to see the Northern Lights and the night sky’s most elusive phenomenon, Zodiacal Light. Finally, we have the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter on 1 March when the two planets will pass within the width of a full Moon of each other. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 6:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 8:30 pm onwards. If you look south, you will still see the winter constellations of Orion, Taurus, Auriga and Gemini which I described in the night sky guide for last month. When looking for them, do bear in mind that they will have moved a little bit to the west. Also, you will now be able to see some of the spring constellations coming into view, with the most significant of these being Leo, which will be high up in the south-east sky.

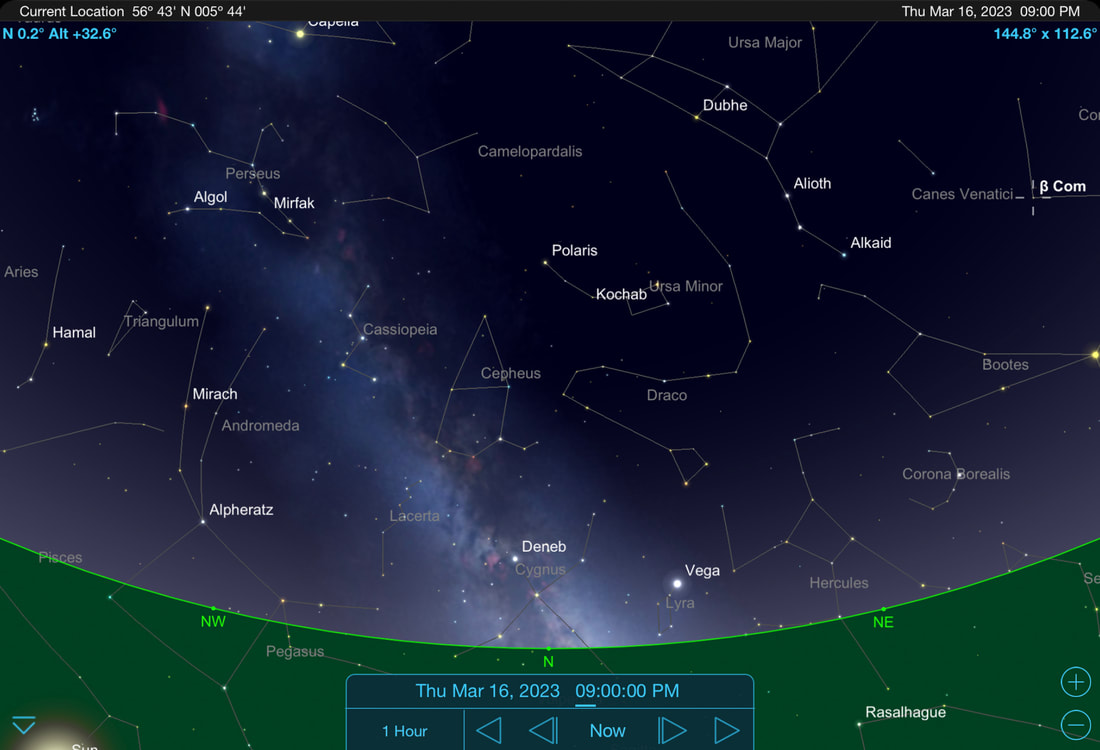

Looking North, the thing to bear in mind is that the constellations you see do not change from month to month, it is only their orientation that changes. You can find the seven stars of the Plough up in the north-east and you can use its two right-hand stars to find the Pole Star, Polaris, which is always in the same position in the sky. Just follow the line between them for about five times its length and you’ll arrive at it. Once you’ve found Polaris, you can use it to get your bearings on any night but bear in mind that all the northern constellations rotate around it in an anticlockwise direction and therefore change their position. It is also worth noting that Polaris is not that bright, with it being about the same brightness as the stars of the Plough. Its significance comes from it being directly above our North Pole. It’s just by chance that this millennium it happens to be very close to the pole of the northern sky, but there is a slow movement of the sky over the centuries that shifts the position of the stars, and 1000 years ago it wasn’t as close as it is now. The constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) was pretty much overhead last month and is now starting to sink down towards the western horizon but it’s still high up. It’s in the shape of a pentagon, with Capella, one of the brightest stars in the sky, at its northern tip. Next to Capella is a triangle of three stars which, though much fainter, makes the whole constellation very recognisable. Below Auriga is the constellation of Perseus who, in Greek mythology, beheaded the Gorgon Medusa for Polydectes and saved Andromeda from the sea monster Cetus. Also, below Perseus, you may be able to pick out the W-shape of the constellation of Cassiopeia, so named after the vain queen Cassiopeia in Greek mythology, who boasted about her unrivalled beauty. The Moon

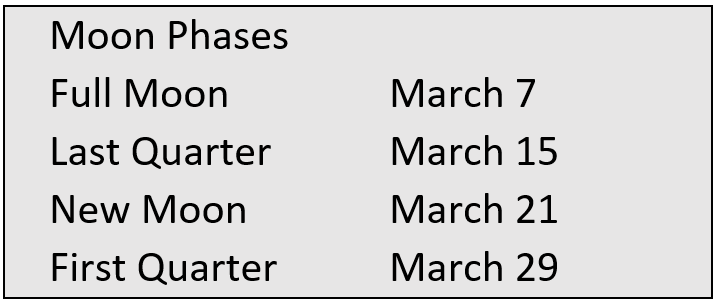

This month’s full Moon is referred to as the Worm Moon because of the earthworms that come out at the end of winter. It is also known as the Crow Moon, Crust Moon, Sap Moon, Sugar Moon, and Chaste Moon. The Old English/Anglo-Saxon name is Lenten Moon. The last quarter Moon is on 15 March and the new Moon (no moon) is on 21 March. This means that a few of days before, on 18 and 19 March, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the southeast around sunrise at about 6:30 am. Alternatively, a few of days later, on 22 March, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets with Jupiter just above it. On the following evening, 23 March, a slightly thicker crescent Moon will be higher up in the western sky, sitting about halfway between Jupiter and Venus. Jupiter will be below it and Venus will be above it. The Moon will be higher still on 24 March, this time sitting just above and to the left of Venus. We have a first quarter Moon (a half moon) on 29 March, and you will find it high in the southern sky, sitting just below Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini. The night before, it will be sitting just above Mars. The PlanetsIf, during February, you’ve been looking over to the western horizon as darkness falls, you will have spotted a brilliantly shining Venus and you may have noticed that it has been getting higher and moving closer to Jupiter as the nights pass. On 1 March, these two brightest planets will be in conjunction, when they will pass within 0.5 degrees (the width of a full Moon) of each other. That's equivalent to the width of your pinkie when held out at arm's length. Venus will dominate the scene because this Evening Star will be shining about 5 times brighter than the gas giant, Jupiter. Be sure to look for them before they drop below the horizon at around 8:30 pm. As the month progresses, Jupiter will reduce in brightness because it is moving closer to the Sun and by the month end, it will have dropped down into the twilight glow and will be lost from sight. Meanwhile, Venus will rise higher and higher into the darker part of the night-time sky, increasing in brightness as it does so and by the end of the month it will be above the horizon until around 11:00 pm. Uranus is now well below and to the left of the Pleiades, about halfway between Taurus and Aries. It sets at around 1:30 am and you will need a telescope to spot it because it is very faint. By the end of the month, Venus will be sitting very close to it. Mars is visible for a good part of the night, before setting at around 2:30 am. You will find it high up in the southern sky, above Orion and Taurus and, as the month progresses, it will be moving towards Gemini and getting dimmer as it does so. The Moon will be close to it on 27 and 28 March. Mercury, Saturn and Neptune are lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersWe in a quiet period for meteor showers and this lasts until 14 April, which is when the Lyrid meteor shower becomes active. It will peak on the night of 22-23 April and the best times to look for meteors will be from late evening on April 21 until dawn on April 22 and late evening on April 22 until dawn on April 23. It should be a good year for spotting them because the new Moon falls on 19 April, meaning that there will be no moonlight to spoil the show. Zodiacal LightThe Zodiac is an 8° wide band that straddles the ecliptic, the invisible path that the Sun traces as it moves around the sky and is the region of the sky where we can find the Sun, Moon and planets (except for Pluto). It is only 8° wide because most of the planets have orbits that are only slightly inclined to that of the Earth. The exception is Pluto, whose orbital inclination of 17° takes it out of the zodiac during part of its orbit. At this time of year, the Zodiac rises steeply from the horizon at dusk, meaning now is great for looking out for and observing one of the night sky’s most elusive phenomena: zodiacal light. It appears as a triangular ghostly glow and occurs when the Sun is beneath the horizon and light from it is reflected off a fog of tiny interplanetary dust particles that fill our inner Solar System. Fainter than the Milky Way, it’s so difficult to see and many astronomers have never witnessed it. However, if you go somewhere with little or no night pollution on a night when the moon is out of the sky and look west in the hour or two after sunset, you may be lucky enough to spot this faint pyramid of light rising from the horizon. The best time to look for zodiacal light in the coming month will be on the days either side of the equinox (20 March) as this coincides with a New Moon, meaning that there will be no moonlight to drown it out. With Venus and Jupiter being low down in the west after sunset, they’ll be visible close to or in the zodiacal light. Shortly after that, on 23 and 24 March, a thin crescent Moon will also be sitting in the midst of this triangular beam of light. Spring Equinox & Northern LightsThe Spring Equinox is when night and day are nearly exactly the same length (12 hours). It also marks the start of astronomical spring and when the days start to become longer than the nights and although it is referred to as a day by many people, it is actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the Sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the Sun. For 2023, this will be at 9:24 pm on Monday 20 March.

The Spring Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Finally, if you do want to catch a glimpse of the “Merry Dancers”, be sure to keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on the web and on social media. Good sources for forecast and alerts are AuroraWatch UK, Glendale Skye Auroras and Aurora Research Scotland. |

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved