|

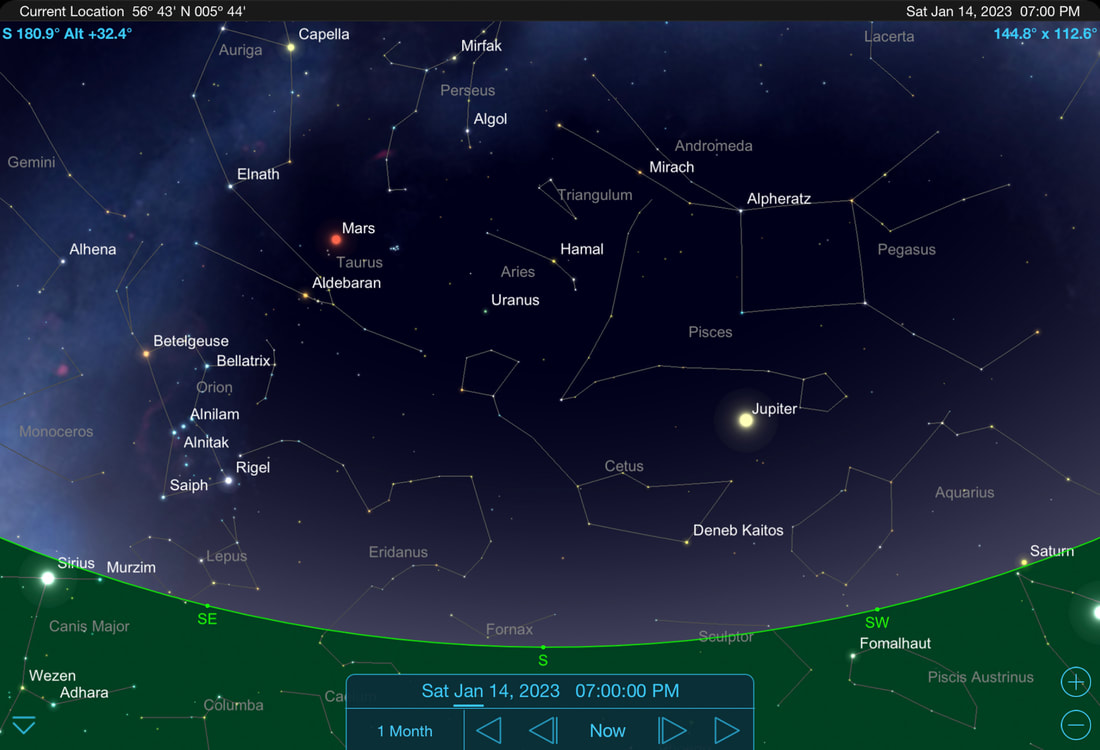

January and the start of the year brings us a dazzling array of stars to find our way through, with Betelgeuse and Rigel blazing in Orion (the Hunter), glorious Sirius in Canis Major (the Great Dog) and the bright red Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull). There is also Capella crowning Auriga (the Charioteer) and Castor and Pollux (the celestial Twins) in Gemini. The peak of the Quadrantid meteor shower is on the night of 3-4 January but unfortunately bright moonlight will spoil the show this year. Instead, why not marvel at the Evening Star, Venus, because it will be shining brightly over in the southwest at nightfall. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 4:15 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 6:15 pm onwards. As darkness falls, the most obvious constellation you’ll see is Orion (The Hunter), with its three bright stars in a line, surrounded by a quadrilateral of other stars. You see it rising in the east not long after dark and by 10:00 pm it will be up there in the centre of the southern sky. As it is the brightest constellation in the sky, you’ll be able to see it even when there is a bright moon or some light pollution.

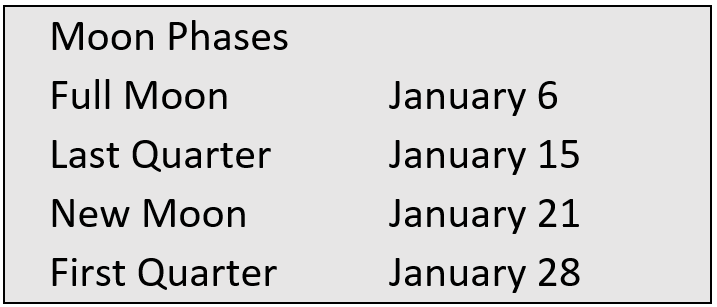

You will find Auriga (the Charioteer) directly above Orion. Its brightest star is Capella and it is at the top of a great pentagon of stars that make up the Charioteer’s pointed helmet. At this time of the year, Capella is almost overhead and there is a little group of three fainter stars just to one side of it. The four other stars that complete the pentagon and make up the rest of the constellation can be found by moving in a clockwise direction down from Capella, round to the left and back up again. If you follow the line of Orion’s belt heading left and slightly down, you will find Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. It is in Canis Major, the Greater Dog, a constellation that and appears very low down at our northern latitude. This can cause it to twinkle quite strongly, especially on a clear frosty night. Canis Major is just one of Orion’s dogs. The other, Canis Minor or the Lesser Dog, can be found directly to his left and its main star is Procyon, the 8th brightest star in the sky. Above Procyon are two stars, Castor and Pollux, which mark the heads of the Twins, Gemini. The bodies of the Twins are the two lines of stars which extend towards Orion. Another thing you can see in the southern sky is the Winter Circle, a pattern of stars that is not a constellation. It’s made up of a lot of separate stars, in different constellations, so it’s what is called an asterism. It doesn’t form a perfect circle, but instead a hexagon that you can find if you start at Capella and move clockwise to Aldebaran, Rigel, Sirius, Procyon, Pollux, and Castor. In addition to the Winter Circle, Orion’s bright star Betelgeuse forms an equilateral triangle with the stars Sirius and Procyon. This what is called the Winter Triangle. If you go back to Orion’s belt and look carefully about halfway down between it and the two stars that mark the Hunter’s left and right feet, you should be able to see a bright patch. This is the Orion Nebula, one of the brightest nebulae, or clouds of gas from which stars are born in the sky. One of many in our Milky Way galaxy, it lies roughly 1,300 light-years from Earth and is some 30 to 40 light-years in diameter. Look at it with binoculars or a telescope and you should see swirls of gas, though the darker and clearer the sky you have, the better you will see this. In it, you should also be able to pick out The Trapezium Cluster, which is made up of four bright stars that are only a million or so years old, babies on the scale of star lifetimes. Looking North, the thing to bear in mind is that the constellations you see do not change from month to month, it is only their orientation that changes. Look for the seven stars of the Plough, up in the north-east, and the W-shape of Cassiopeia, high up in the north-west at this time of year. The Plough is known as the Big Dipper in North America. Use its two top stars to draw a line left (west) towards the Pole Star, Polaris, which is always in the same position in the sky. Once you’ve found Polaris, you can use it to get your bearings on any night, as all the other northern constellations wheel around in an anticlockwise direction as the months pass. Polaris is a second-magnitude star, about the same as the stars in the Plough or Cassiopeia, so don’t expect anything particularly bright. It’s just by chance that this millennium it happens to be very close to the north pole of the sky. There is a slow movement of the sky over the centuries, and this shifts the position of the stars, so 1000 years ago it wasn’t as close to the pole as it is now. The MoonThis month’s full Moon is called the Wolf Moon, after the howling of hungry wolves lamenting the scarcity of food in midwinter and other names include the Moon After Yule, Old Moon, Ice Moon, and Snow Moon. It becomes 100% full at precisely 11:08 pm on 6 January meaning that it will appear full on the nights of 5-6 January, 6-7 January, and 7-8 January. It will rise in the northeast at around 3:00 pm on 5 January, at around after 3:30 pm on 6 January and at about 4:15 pm on 7 January. The last quarter Moon is on 15 January and the new Moon (no moon) is on 21 January so a couple of days before on 18 and 19 January you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the southeast in the twilight hours before sunrise. Similarly, a few of days later, on 23 January, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting close to the southwest horizon as darkness falls, with Venus and Saturn a little to its right. The following day, on 24 January, a slightly thicker crescent Moon will be higher in the southwestern sky with Venus and Saturn down to its right and Jupiter up to its left. It will move closer to Jupiter on 25 January and past Jupiter on 26 January. We have a first quarter Moon (a half moon) on 28 January and a couple of days later, on 30 January, it will be very close to Mars, Aldebaran, and the Pleiades. The PlanetsIf you look over to the southwestern horizon as darkness falls, you will spot a brilliantly shining Venus. From now on, the Evening Star is brighter than any of the stars and other planets in the night sky and it will be present in the dusk sky until July. As the days pass, Venus will be moving towards a still reasonably bright Saturn. On 22 January, you will see them at their closest grouping if you look over to the southwestern horizon after sunset. A day later, on 23 January, this grouping will be joined by a crescent Moon. Jupiter, although reducing in brightness as the weeks pass, is still shining reasonably brightly and can be seen high up in the southern sky as darkness falls. It sets in the southwest at around 10:00 pm and if you look at it through binoculars or a telescope before then, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons. The largest moon, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. Mars is visible for most of the night long, setting at around 5:00 am. You will find it high up in the eastern sky as darkness falls and you can follow it on its journey across to the north-western horizon, with Aldebaran to its lower left and the Pleiades to its lower right. You’ll find Uranus below and to the left of the Pleiades, about halfway between Taurus and Aries. It sets at around 2:30 am and you will need a telescope to spot it as it is quite faint. Neptune is fainter still and sets at about 9:30 pm. Look for it through a telescope about a quarter of the way along the line going from Jupiter to Saturn. Mercury is moving further away from the Sun’s glare, reaching greatest separation on 30 January. This makes now a good time to look for this innermost planet and you’ll find low in the southeast before sunrise from about the middle of the month Meteor ShowersThe Quadrantid meteor shower, always the year’s first meteor shower, will peak on the night of 3-4 January. Unfortunately, this most prolific of meteor shows will be spoilt by bright moonlight because the full Moon is only 3 nights later, on 6 January.

If you do decide to try and spot one of its 100 meteors per hour, then the best time is probably in the hour or so of true darkness that occurs after the Moon has set early on the morning of 4 January. You’ll find its radiant point in the north sky, directly below The Plough, but do bear in mind that you don’t have to look north as the meteors will appear across all the sky.

0 Comments

|

Steven Marshall Photography, Rockpool House, Resipole, Strontian, Acharacle, PH36 4HX

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 01967 431 335 | Mobile: 07585 910 058 | Email: [email protected]

All Images & Text Copyright © 2024 - Steven Marshall - All Rights Reserved