|

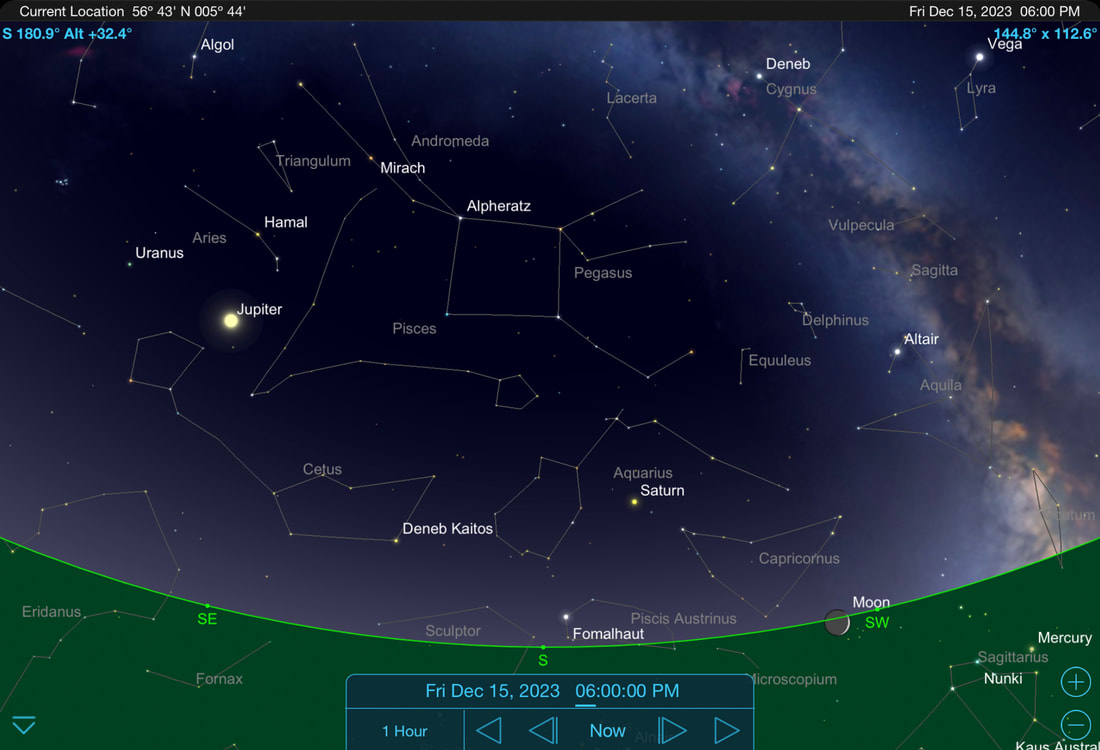

You don’t have to be out late to go stargazing this month because December is the month of the Winter Solstice and when we have our shortest day with under 7 hours of daylight. Although most of the bright stars are now missing from our sky, it is a good time to spot the Andromeda Galaxy, the closest spiral galaxy to our own galaxy, the Milky Way. All the planets, except for Mars will be visible during the hours of darkness this month and can be spotted with a pair of binoculars or a telescope. Finally, we have the Geminids meteor shower peaking on the morning of 14 December and with no Moon in the sky to spoil the show, it may be possible to see up to 120 meteors an hour, so do look out for them then. The ConstellationsThis month the sun sets around 4:00 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 6:00 pm. As with November, there is a great signpost in the form of the Square of Pegasus to help you find your way around the sky. It is a huge square made up of four stars of nearly equal brightness: Scheat, Alpheratz, Markab and Algenib and you should be able to see it high up in the south, above Jupiter in the early evening sky. The top left star of the Square is Alpheratz. It is the brightest star in the constellation of Andromeda, which is marked by a line of three more stars running up and to the left of it. You can use this line to find the Andromeda Galaxy, one of the most famous features of the night sky and the nearest spiral galaxy to our own, the Milky Way. The best way to find it is to start Alpheratz and go a further two stars along the line, turn right and count another two faint stars along, and the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) will be close to the second faint star. If you are in a town, you’ll probably need a pair of binoculars to spot it, but if you’re in a dark place out in the country, you should be able to pick it out without using binoculars.

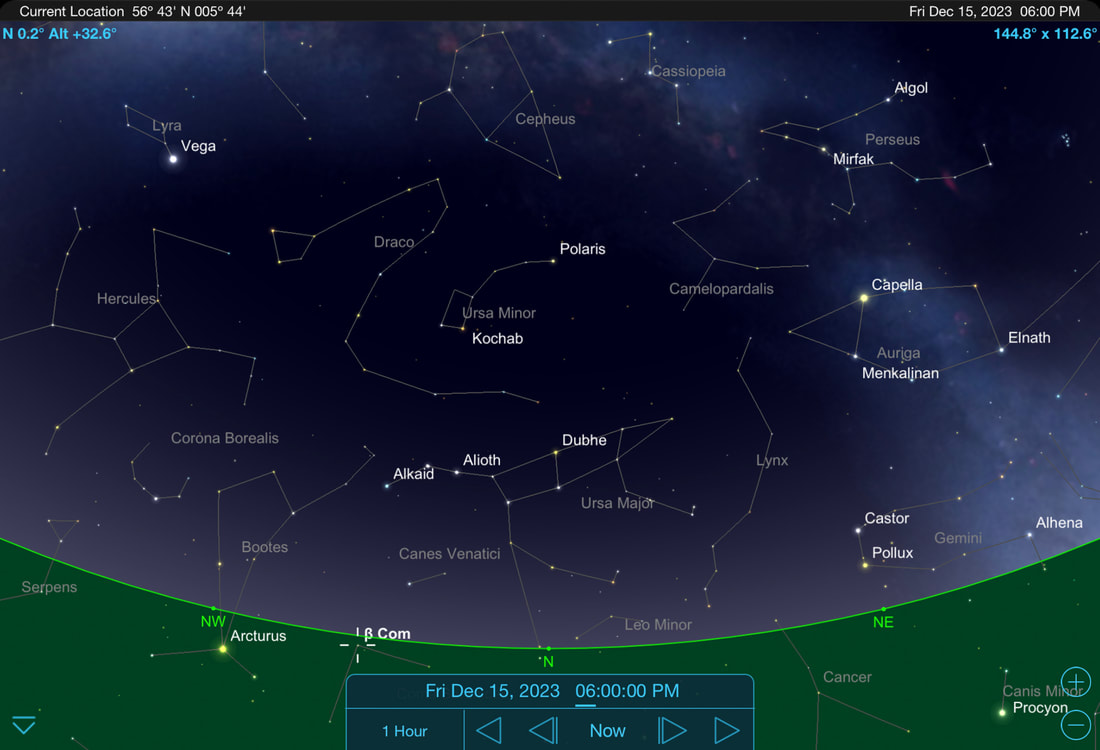

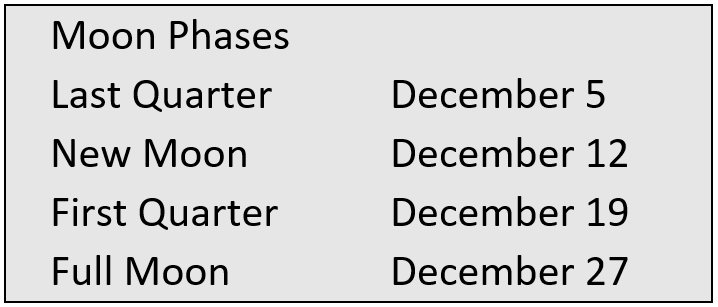

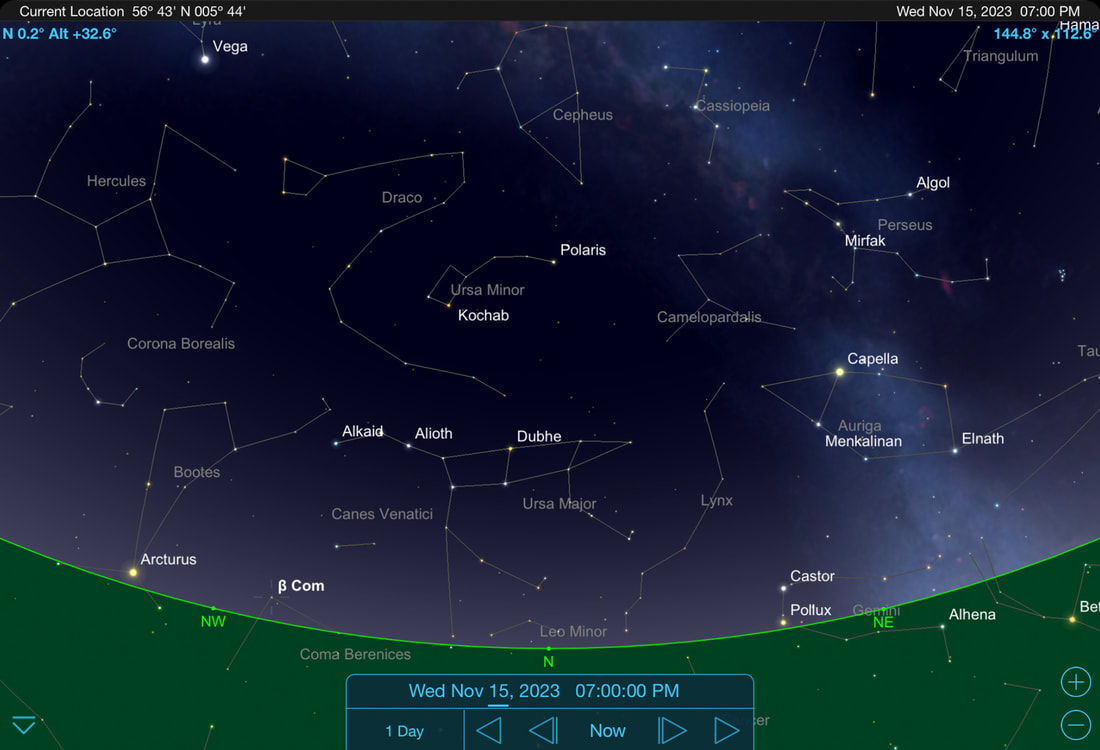

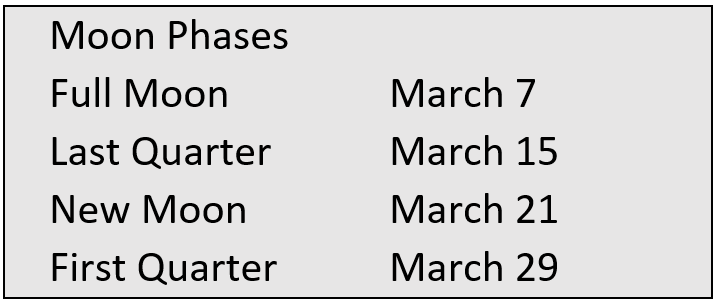

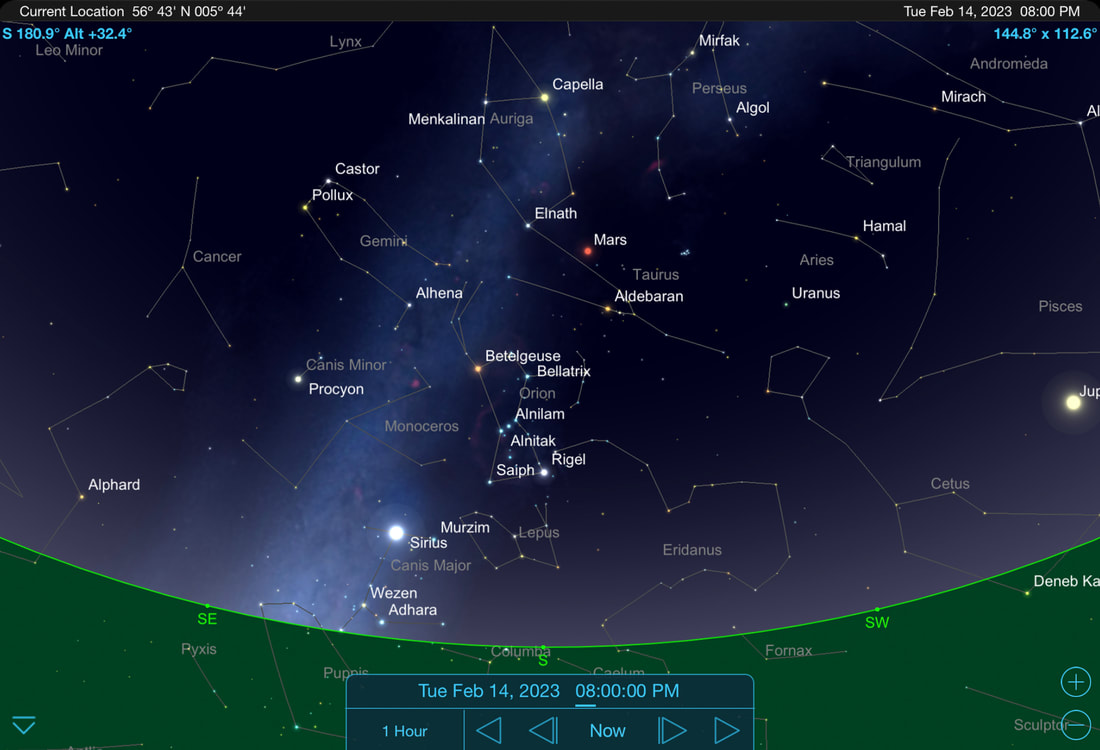

There will be more about Taurus and Orion next month, but for the moment, draw a line using the three stars in Orion's belt and follow it through Aldebaran and you’ll find the Pleiades star cluster (M45) a bit beyond it. This cluster is the brightest open constellation we can see in the night sky and is a grouping of more than 1,400 stars, seven of which are visible to the naked eye. The name comes from the early Greeks who referred to the constellation as the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters who were daughters of Atlas and Pleione. These stars are mentioned three times in the Bible and are linked to origin stories for many American Indian tribes. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. In December the familiar Plough asterism, which many people recognise, is moving from the north to the north-east. If you follow its two right-hand stars upward and veer a little bit to the right, you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look high up over to the north-east, you can see Castor and Pollux, the two brightest stars in the Constellation of Gemini (the Twins), which represent the heads of The Twins. Meanwhile, low down in the North-West, you will find Vega, the brightest star in the Constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). It is the fifth-brightest star in the night sky, and the second-brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere after Arcturus. The MoonThere was a full Moon on 27 November, so we start the month with an 82% waning gibbous Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 5 December. The new Moon (no moon) is on 12 December and a few days before that, on 8 December, you can see a crescent Moon sitting above and to the right of Venus over in the southeast from 3:00 am and until the sun rises at around 8:45 am. You should also be able to see a crescent Moon at daybreak on 9 December, when it will be at its closest to Venus and again on 10 December when it will be below and to the left of the Morning Star. Alternatively, a few days later, on 15 and 16 December, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the southern sky as the Sun sets, while on 17 December the Moon will be very close to Saturn. The Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 0:33 am on 27 December. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 25-26 December, 26-27 December and 27-28 December. It will rise in the northeast at around 2:00 pm on 25 December, at about 2:30 pm on 26 December and at about 3:30 pm on 27 December. This month’s full Moon is called the Cold Moon because December is the first month of winter. Its Old English/Anglo-Saxon name is the Moon Before Yule, while another name for it is the Wolf Moon, however, this is more commonly used for January’s Full Moon. The PlanetsSoon after sunset at the beginning of the month, use binoculars or a telescope to look out for Mercury low down on the southwestern horizon. The innermost planet will be at its greatest separation from the Sun on 4 December, meaning that it will be shining at its brightest. After that, it will fade each night before disappearing in the twilight glow during the second week of the month. As darkness falls, you will also see Saturn sitting above the southern horizon. It will be visible until it sets at around 10:00 pm and if your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own Moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, so you will need a telescope to pick this outermost planet in the boundary between Aquarius and Pisces in the southeastern sky. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. It sets at just after midnight. Next is Jupiter, which you will find it over in the east as darkness falls and it will remain visible until it sets at around 4:30 am. If you look at it through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. If you use a telescope, you will be able to see its roiling clouds and the huge storm known as the Great Red Spot. Uranus lies to the left of Jupiter and does not set until around 6:00 am. You may be able to spot it with the naked eye, but you’ll stand a much better chance of seeing it if you use binoculars or a telescope. In fact, a telescope should reveal its disc and its largest moons. Next up is Venus, rising in the southeastern sky at around 5:00 am and continuing to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky except for the Moon. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersDecember is the month for viewing the shooting stars of the Geminids Meteor Shower. Unusually, they are not debris from a comet, but rather debris from an asteroid called Phaethon. The Geminids have become more plentiful in recent years and are considered by many to be the best meteor shower of the year. They are active from 4-17 December and during their peak, which this year is on 14 December, it can be possible to see around 120 meteors per hour. Their radiant point is in the north-east sky, in the Constellation of Gemini (The Twins) and close to Castor, one of its two bright stars. Although this is where they originate from, you’ll be able to see them at any point across the sky as they burn up in the upper atmosphere, some 60 miles (100 km) above Earth’s surface. The best time to look for them is normally when the radiant point is at its highest in the sky, which will be at around 2:00 am. This year, there will be a waxing crescent Moon on 14 December, which sets at 4:30 pm, meaning that it will not illuminate the sky and spoil the show. Winter SolsticeThis year, the Winter Solstice will occur on 22 December at 3:27 am and is the exact moment when the northern hemisphere is tilted furthest away from the Sun. However, many people refer to the Winter Solstice as the Shortest Day of the year, when the number of hours of daylight are at their minimum and the number of hours of night are at their maximum. On 22 December this year, our sunrise will be 8:55:40 am and our sunset will be 3:47:34 pm, giving us only 6 hours, 51 minutes and 54 seconds of daytime.

0 Comments

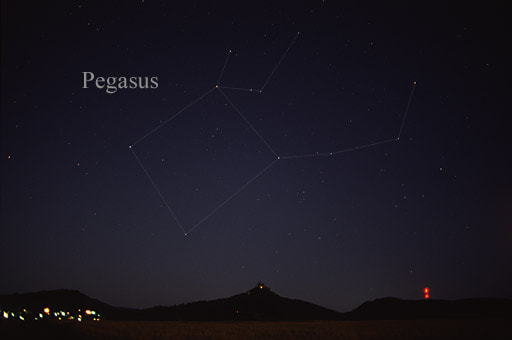

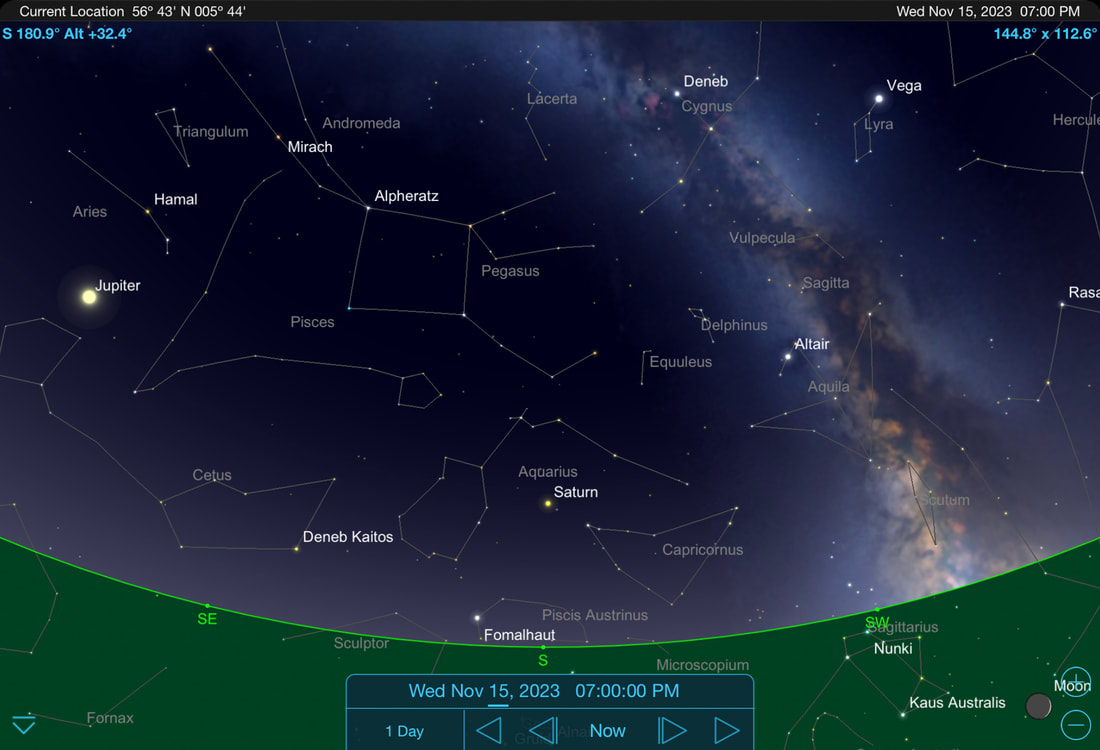

The clocks have changed, and the Sun now sets not long after 4:00 pm to give us long dark nights for stargazing. The Great Square of Pegasus is now in the southern sky and available for us to use to find our way around the many constellations that surround it. Both Jupiter and Venus are shining bright, with Jupiter being at its brightness this month, giving us the opportunity for some great planet watching. Finally, you may be able to spot shooting stars produced as a steady stream from the Taurid meteor showers in the first part of the month, followed by a second opportunity to spot some more when the Leonids meteor shower peaks on 17 November. The ConstellationsFollowing the clock change at end of last month, the sun now sets not long after 4:00 pm, meaning that the stars and constellations start to become visible from about 5:30 pm onwards. During the previous three months we have been watching the Milky Way get lower and lower in the southern night sky and you may have noticed the constellations in the south getting dimmer. This is because the position of the Earth is now such that we are looking out of the plane of our galaxy and into the rest of the universe. The Milky Way has not gone altogether, and you can see it over in the west along with the Summer Triangle of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb, which we have been using to navigate our way around the night sky in previous months. However, it is now better to use the Great Square of Pegasus, a large square asterism made up of 4 stars of nearly equal brightness which you can find high up in the southern night sky. The four stars are Scheat, Alpheratz, Markab and Algenib and you will need to look carefully to find them as they are all of second magnitude, so they aren’t the brightest.

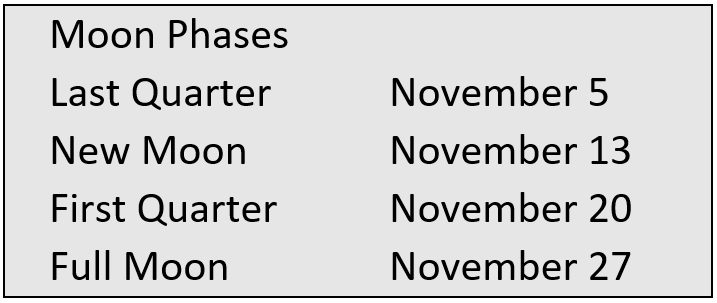

If you follow the diagonal down from the top left of the Square to beyond its bottom right star, you’ll come to a faint group of stars known as the Water Jar of Aquarius. It is an asterism formed by four relatively bright stars in the constellation of Aquarius (the Water-Carrier). It is easily recognised by its arrow shape, which looks a bit like a fighter plane with swept wings. Though it’s not the brightest part of Aquarius, it’s a good pattern that helps you to find its other stars. A line of stars in the constellation of Andromeda stretches from the top left edge of the Square a constellation that is named after the daughter of Cassiopeia who, in the Greek myth, was chained to a rock to be eaten by the sea monster Cetus but was saved from death by Perseus. The constellation is the home of the Andromeda Galaxy which, at approximately 2.5 million light-years from Earth, is the nearest spiral galaxy to our own galaxy, the Milky Way. It is also the most distant object that you are likely to see without an optical aid. However, if you can’t find it with the naked eye, use binoculars to look for a little oval blur. Below Andromeda and to the left of Pegasus is where you will find the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). It is very faint and difficult to see, so the best way to find it is to look directly below the Square of Pegasus for the Circlet of Pisces, which is a pentagonal asterism of 5 stars that marks the head of the Western Fish. Once you’ve found it, go on from there to catch the Eastern Fish which is jumping upward to the east of the Square of Pegasus. The entire constellation looks like the letter V. Below Pisces is the constellation of Cetus, the Sea Monster which in Greek mythology both Perseus and Heracles needed to slay. You’ll find its tail marked by a fairly bright star called Diphda located low down in the sky, which is almost directly below the left-hand edge of the Square of Pegasus, while further over to the left and up a little, you’ll find Menkar, a reasonably bright star that marks its head. You may have noticed that all the constellations in this part of the sky have watery connections. It is said that this is because the Sun travelled through these constellations during the wet season in ancient Mesopotamia, which was from November to March, and flooding was a major problem. The naming of many of our constellations dates from that location and time. Finally, to the east of the Square is Aries, the Ram, whose three main stars form an easily recognised triangle. You’ll find another more regular triangle close to this one which is actually called Tringulum, the Triangle. It contains the nearby galaxy M33, which will be visible with binoculars if you have a reasonably dark sky. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, except that their orientation varies. This month the familiar Plough asterism, which many people will recognise, is low down in the north just now, with its rectangular end almost directly below Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. It is a yellow giant star, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer), the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, and the third brightest in the northern celestial hemisphere after Arcturus and Vega. The MoonThere was a full Moon on 28 October, so we start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 5 November. The new Moon (no moon) is on 13 November and a few days before that, on 9 November, you can see a crescent Moon sitting very close to a bright shining Venus over in the southeast from 3:00 am until the sun rises at just before 8:00 am. You should also be able to see a crescent Moon at daybreak on 10 and 11 November, but it will be too close to the Sun on 12 October to be visible. Alternatively, a few days later, on 16 and 17 November, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the southern sky as the Sun sets. The Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 9:16 am on 27 November. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 26-27 November, 27-28 November, and 28-29 November. It will rise in the northeast at around 3:00 pm on 26 November, at about 3:20 pm on 27 November and at about 3:50 pm on 28 November. This month’s full Moon is called the Beaver Moon. There is disagreement over the origin this name with some saying that it comes from Native Americans setting beaver traps during this month, while others say it comes from the heavy activity of beavers building their winter dams. It is also known as the Frosty Moon, and along with December’s Full Moon, some called it the Oak Moon. Traditionally, if the Beaver Moon is the last Full Moon before the winter solstice, it is also called the Mourning Moon. The PlanetsAs darkness falls, you will see Saturn sitting above the south-eastern horizon. It will be visible until it sets at around 11:30 pm and if your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own Moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out on the border between Aquarius and Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. It sets at about 2:00 am. Next to see is Jupiter, rising well over in the east at around 4:00 pm. It is at its closest to Earth on 1 November at 370 million miles away. Two days later it’s at opposition, when it is in line with the Sun and Earth and it will be shining at its brightness as a result. If you look at it through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. If you use a telescope, you will be able to see its roiling clouds and the huge storm know as the Great Red Spot. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about 10-15 minutes later. You may be able to spot it with the naked eye but will stand a much better chance of seeing it if you use binoculars or a telescope. In fact, a telescope should reveal its disc and its largest moons. Next up is Venus, rising in the eastern sky at around 3:00 am and continuing to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky except for the Moon. Mercury and Mars are too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersDuring the first part of the month, the South and North Taurid meteor showers are very noticeable. Unlike other meteor showers, they don’t have strong peaks but instead have “staying power” and produce a steady stream of meteors over a number of weeks. The South Taurids are active from about 10 September to 20 November, while the North Taurids are active from about 20 October to 10 December.

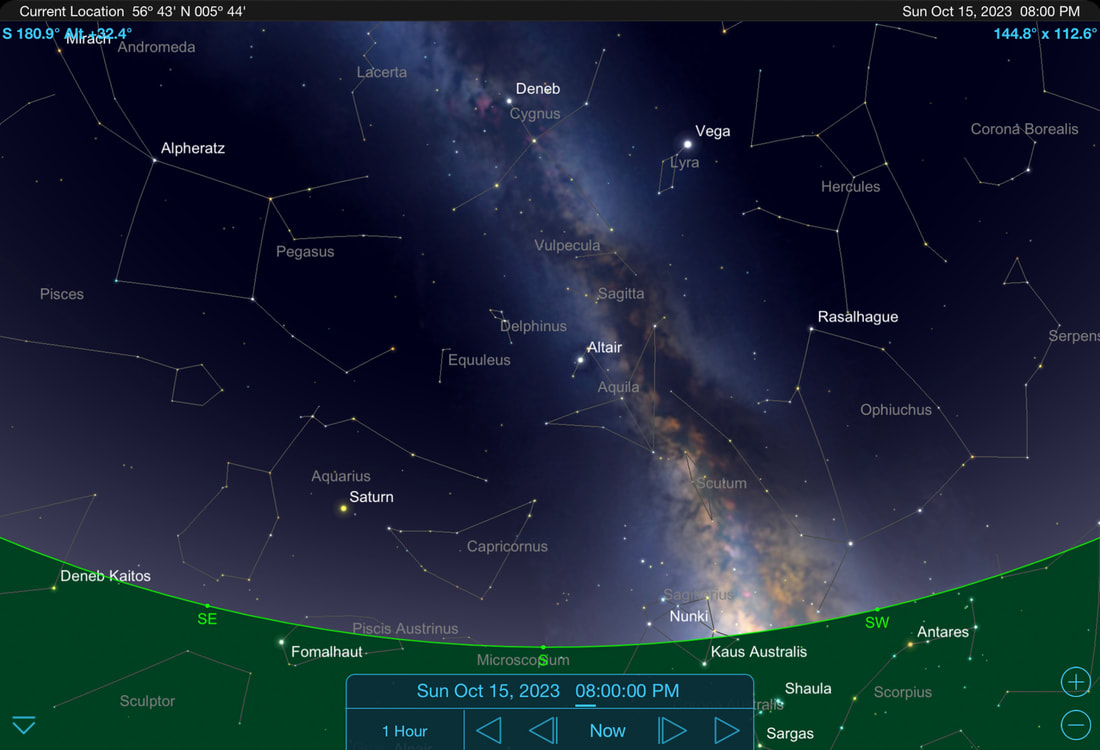

These showers produce about 5 meteors/hour each and because they overlap up until 20 November, you can expect to see up to 10 meteors/hour during the first 2-3 weeks of the month. However, the best nights to look for them will be during the few nights either side of the new Moon on 13 November because there will be little or no moonlight to drown them out. The showers’ radiant points, the part of the sky from which the meteors originate, rise in early evening and are at their highest in the sky around midnight, so this will be the best time on these nights to look for them. We also have the Leonid meteor shower this month and it is known for periodic storms of historic proportions, when shooting stars fall like rain. While no storm is predicted for the 2023 Leonids, you can still catch plenty of meteors between 3 November and 2 December. This meteor shower peaks the morning of 17 November. This is only a few days after a new Moon, giving us a near moonless night, meaning that it is a good year to look for them. The shower’s radiant rises around midnight, so the best time to look for them will be from then until dawn on 18 November. We had the Autumnal Equinox at the end of last month and with it comes ever shorter days and longer nights, making it ideal for stargazing. Although there are not too many bright stars in the lower half of the sky, there is much to see higher up, with the Great Square of Pegasus entering our southern night sky. There’s also a chance of seeing some shooting stars, with the peak of the Draconids Meteor Shower on the night of 8/9 October and the peak of the Orionids meteor shower on the night of 21/22 October. Finally, there will be a partial lunar eclipse visible to us here in the UK on the night of 28th October. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 6:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 8:00 pm onwards. Even though we are now into Autumn, the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb, is still visible and can be used to navigate your way around the night sky. Start off by finding Vega, a really bright white star which will be high up in the sky to the South-West. Just face south, look up, then look right and you will find it. Next is Altair, which you will find below Vega, halfway down towards the horizon and slightly to the left. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and above and to the left of Vega. The Milky Way, which has dominated the night sky over the last couple of months can still be seen during the early part of the night. Just trace a line down from Deneb, through Altair and you should be able to make out its band of stars as it flows down to the horizon, with the last of its cloudy core visible and well over to the right of Saturn as it sits above the southern horizon. At the moment there are not many bright stars in the lower part of the southern sky so, if you are in an area with light-pollution, look higher up and you should be able to pick out some constellations. Below Vega, you will see the 4 other main stars that make up the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre). These form a small parallelogram and make up the body of the Lyre – the sky’s only musical instrument.

Finally, looking at Altair, you will find the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) because Altair is its brightest star. Altair also has outstretched wings, though they are not as obvious at the wings of Cygnus. In between these two flying birds is the constellation of Sagitta (the Arrow), a dim but distinctive shape which is reasonably easy to pick out. Another small but easily seen constellation called Delphinus (the Dolphin) is nearby and it also looks like what it’s meant to be. If you look high up and over to the South-East, you’ll find the Square of Pegasus sitting above the halfway point between Saturn and a bright shining Jupiter. This asterism is made up of 4 stars of nearly equal brightness in a large square pattern and the stars are Scheat, Alpheratz, Markab and Algenib. The constellation of Pegasus represents the Flying Horse of Greek mythology and the Square marks the horse’s body. You may find it difficult to make out the horse because it is upside down and the constellation represents only the top half of its body and its head. However, you may be able to pick out Enif, the constellation’s brightest star which will be about halfway between the bottom right of the Square and Altair. Enif is an orange supergiant star that is 5,000 times brighter than the Sun and it represents the horse’s nose. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. In October the familiar Plough asterism, which many people will recognise, is moving from the north-west to the north. Follow its two right-hand stars upward, veer a little bit to the right and you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. It is a yellow giant star, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer), the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, and the third-brightest in the northern celestial hemisphere after Arcturus and Vega. The MoonThere was a Supermoon on 29 September, so we start the month with an almost full Moon. On 1 October, it very close to Jupiter, over in the eastern sky. It becomes a last quarter Moon on 6 October and on that night, you can find it near Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini.

We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 22 October. You will see it in the southern sky as darkness falls and it will remain visible until it sets at 11:30 pm. Then, on 23 and 24 October, you will find it a bit further over to the south-east and close to Saturn as darkness falls. Next, the Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 9:24 pm on 28 October. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 27-28 October, 28-29 October, and 29-30 October. It will rise in the east at around 5:30 pm on 27 October and at about 10 minutes later on 28 October. It will rise just over an hour later on 29 October, at around 4:45 pm, with the jump of an hour being due to the clocks changing from British Summer Time to Greenwich Mean Time on that day. As well as there being a full Moon on 28 October, there will also be a partial lunar eclipse. It will be visible from the UK, beginning at 8:35 pm and ending at 9:53 pm. So if the sky is clear, look out for it and you will see part of the Moon being clipped by Earth’s dark umbral shadow. This month’s full Moon is called the Hunter’s Moon because traditionally, people in the Northern Hemisphere spent the month of October preparing for the coming winter by hunting, slaughtering, and preserving meats for use as food. Like the last month’s Harvest Moon, the Hunter's Moon is also particularly bright and long in the sky, giving hunters the opportunity to stalk prey at night. Other names include the travel moon and the dying grass moon. The PlanetsThis month, the first planet you will see is Saturn, which will be sitting above the south-eastern horizon as darkness falls. It will be visible until it sets at around 2:30 am and if your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own Moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. It sets at about 5:00 am. Next to see is Jupiter, rising over in the east at around 7:00 pm. If you look at Jupiter through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about 5-10 minutes later and may only be visible through binoculars or a telescope. Next, rising in the eastern at around 3:15 am, is Venus continuing to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky with the exception of the Moon. For the first few mornings of October, you may be able to catch Mercury very low down on the eastern horizon as it rises in the east at around 5:00 am. However, after only a few days it will drop down into the pre-dawn glow and disappear from sight. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersThe Orionid meteors fly each year between about October 2 to November 7 and are caused by debris from Halley’s Comet smashing into the Earth’s atmosphere. You can spot them from the start of the month, but you can see the greatest number at the meteor shower’s peak on the night of 21-22 October.

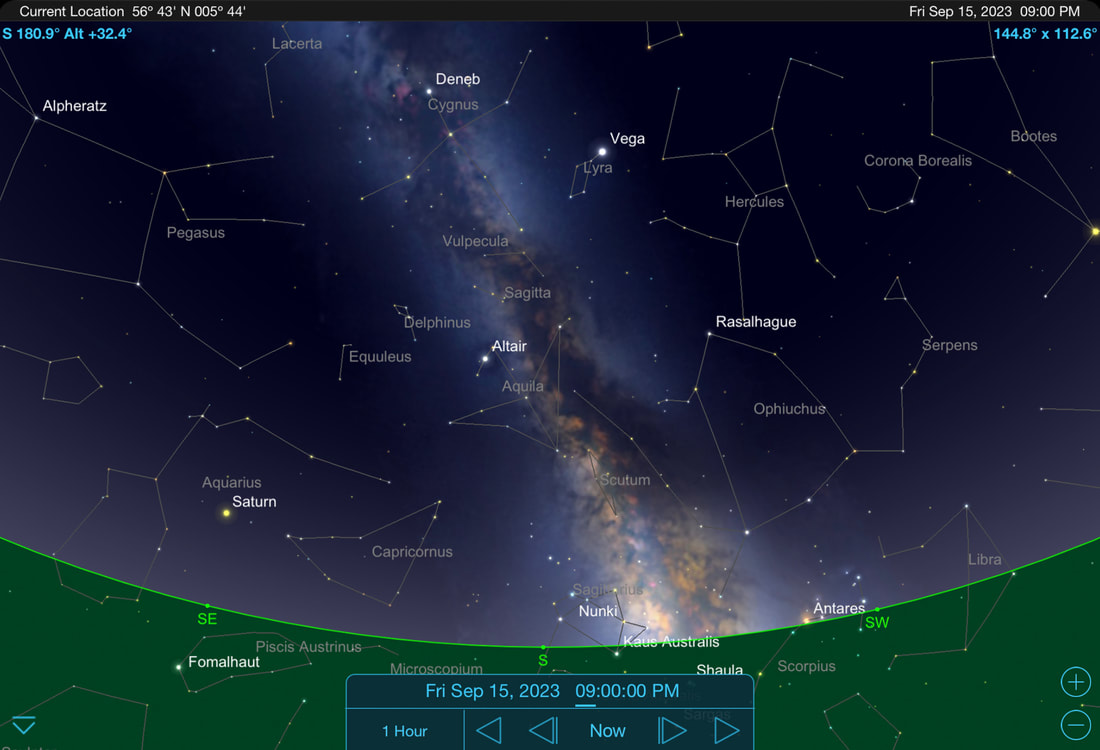

In a good year, with little or no Moon, you can expect to see about 10-20 meteors/hour at the peak. This will be the case this year because the first quarter Moon will set at around midnight and therefore not interfere with the best viewing time of around 2:00 am, This is when the meteor shower’s radiant point (the area of the sky where the meteors seem to originate) is highest in the sky and you will find it to the top left of Orion as it rises in the east. Instead of the Orionids, you could watch for the Draconid meteors from nightfall on October 8, right through to the wee hours of the morning of 9 October. It is an unusual meteor shower because its radiant point stands highest in the sky as darkness falls and this year, this means that the waning crescent Moon (23% illuminated) which doesn’t rise until about 1:00 am, will not interfere with the show. If you do decide to look, you’ll find the radiant point a little bit to the right of Vega and right next to the head of the constellation Draco the Dragon. Also, the Draconids meteor shower is known as “a Sleeper” because in most years it produces only a handful of meteors per hour. However, do look out for them because the Draconids’ unpredictable nature, as seen in both 1933 and 1946, means that you could enjoy thousands of meteors in only one hour. Finally, when watching for the meteors, give yourself at least an hour of observing time, because they will come in spurts, interspersed with lulls. Also remember that your eyes can take as long as 20 minutes to adapt to the darkness of night, so don’t rush the process. Patience is the key to maximising your chances of spotting some. Depending on your point of view, Autumn either starts on 1 September (meteorological autumn) or the 23 September (astronomical autumn). The latter is when the Autumnal Equinox takes place and when the sun is directly above the earth’s equator. On that date, day and night are of equal length and the Sun rises due east and sets due west. With this, the dark nights return and, because it doesn’t get too cold outside, September is a great month for stargazing. According to NASA, the Equinox is a prime time for Northern Lights so, if you want to catch a glimpse of them, do keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on social media. The ConstellationsThis month the sun sets around 8:00 pm and the stars and the constellations become visible from about 9:00 pm onwards. As with July and August, the best way to navigate your way around the night sky is to use the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb. Start off by finding Vega, a really bright white star, which will be directly overhead. Next is Altair, which you will find halfway between Vega and the southern horizon. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and across from Vega. Once you have found the Summer Triangle, you can start to look for some of the constellations in the southern sky. Start off with Vega, the constellation of Lyra’s (the Lyre) brightest star. Below it, you will see the constellation’s four other main stars. These form a small parallelogram and make up the body of the Lyre – the sky’s only musical instrument.

Finally, looking at Altair, which you will find the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) because Altair is its brightest star. Altair also has outstretched wings, though they are not as obvious at the wings of Cygnus, and in Greek mythology, Aquila is identified as the eagle that carried Zeus’ thunderbolts and was once dispatched by the god to carry Ganymede, the young Trojan boy Zeus desired, to Olympus to be the cup bearer of the gods. In between these two flying birds is the constellation of Sagitta (the Arrow), a dim but distinctive shape which is reasonably easy to pick out. Another small but easily seen constellation called Delphinus (the Dolphin) is nearby and it also looks like what it’s meant to be. The two better-known constellations of Capricornus and Aquarius are below Delphinus in the lower part of the sky. They are well known because they are in the Zodiac, the path of the planets but, as they have no very bright stars, you might not be able to pick them out. Capricornus is the Water-Goat and Aquarius is a human, the Water-Carrier. As with August, September is a good month to view the Milky Way. If you trace a line down from Deneb and through Altair, you should be able to make out the Milky Way’s cloudy core well to the right of Saturn, which you’ll find shining bright low down in the south to south-east sky. The cloudy core will be visible up until about 10:00 pm. When you look at the Milky Way, you’ll notice a black band running down it’s middle, between the stars. William Herschel, the first astronomer to map our Galaxy, thought that this was a hole in space, but it is actually a dark swathe of sooty dust, known as the Great Rift in Cygnus, which runs along the disc of our Galaxy. If you look north, you’ll see the same stars as you would in any other month, but their orientation varies from month to month. By September the familiar Plough asterism, which many people recognise, is down over to the north-west. Follow its two right-hand stars upward, veer a little bit to the right and you’ll find Polaris, the Pole Star. If you look over to the north-east you can see Capella. Contrast its colour with that of Vega, which is virtually overhead at this time of year. Capella is a yellow giant star, while Vega is a slightly bluer star than the Sun. The contrast is obvious if you look from one to the other. The MoonThere was a Blue Supermoon on 31 August, so we start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes a last quarter Moon on 6 September, after passing close by Jupiter over in the east, on 4 September. Meanwhile, if you look just above the Moon on 5 September, you should be able to spot the glimmering Pleiades star cluster, a lovely sight through a pair of binoculars.

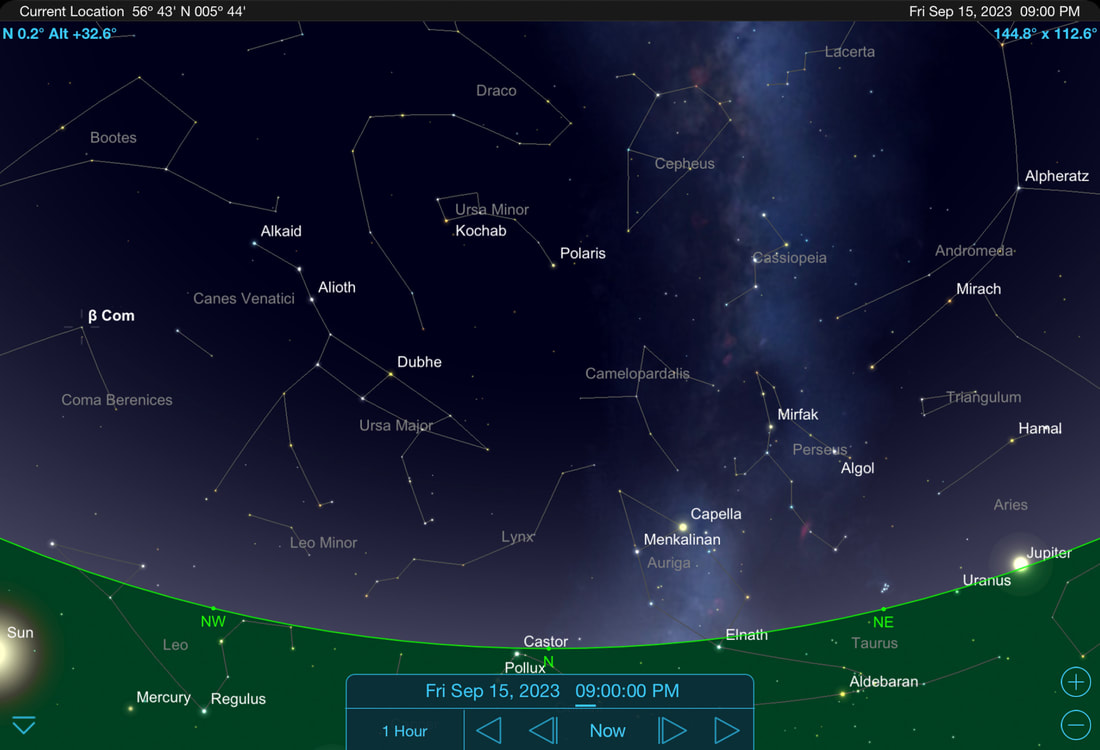

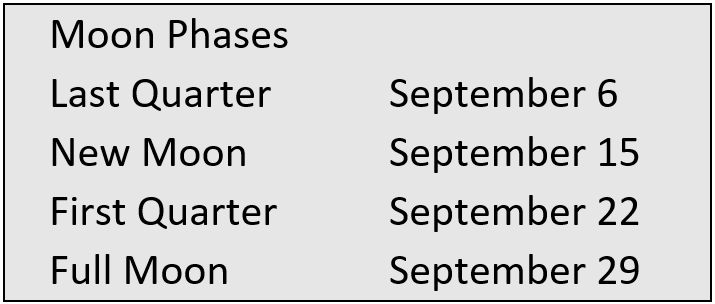

We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 22 September. You will find it in the southern sky in the hour or so after sunset before it sets at around 9:30 pm. Then, a few days later, on 26 September the Moon will be over in the south-east and very close to Saturn. The Moon then becomes 100% full at precisely 10:57 am on 29 September. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 28-29 September, 29-30 September, and 30 September-1 October. It will rise in the east at around 7:00 pm on 28 September, at around 7:15 pm on 29 September and then at around 7:30 pm on 30 September. September’s full moon is called the Corn Moon because this is when crops are gathered at the end of the summer season. At this time of year, the Moon appears particularly bright and rises early, thus letting farmers continue harvesting into the night. This Moon is also sometimes named the Barley Moon and, like this year, it is often the nearest full moon to the autumnal equinox, earning it the title of 'Harvest Moon'. The PlanetsThis month, the first planet you will see is Saturn, which will be sitting above the south-eastern horizon as darkness falls. If your binoculars or telescope magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons when you look at it. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. This is because its distance from Earth means that its brightness is half of that of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye. Next to see is Jupiter, rising over in the east at around 9:00 pm. If you look at Jupiter through binoculars, you will see some tiny starry objects on either side of it. These are its brightest and largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons and will change position each night as they circle this mighty gas giant planet. Uranus will follow close behind Jupiter, rising about quarter an hour later and may only be visible through binoculars or a telescope. Finally, rising in the eastern sky at around 3:30 am, Venus continues to spend this time of the year as the glorious “Morning Star”. It will be easy to spot because it will be shining much brighter than anything else in the sky, apart from the Moon. From about 20 September, Mercury will rise in the east at around 5:00 am, sitting well to the lower left of Venus. It’s at its maximum separation from the Sun on 22 September. Mars is too close to the Sun to be seen this month. Meteor ShowersThe annual Perseid Meteor Shower peaked last month and those of you who were lucky enough to have clear skies around its peak on the night of 12-13 August may have seen some of the brighter meteors shooting across the sky. However, September is not a good month for meteor showers, so we will have to wait until October for the chance to see some more. The Draconids are expected to peak at nightfall on 8 October and the Orionids are expected to peak between midnight and dawn on the night of 21-22 October. Autumnal Equinox & Northern LightsThe Autumnal Equinox is when night and day are nearly exactly the same length (12 hours). It also marks the start of astronomical autumn and when the nights start to become longer than the days. Although the autumnal equinox referred to as a day by many people, it’s actually the exact moment in time when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the Sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the Sun. For 2023, this will be at 7:50 am on Saturday 23 September.

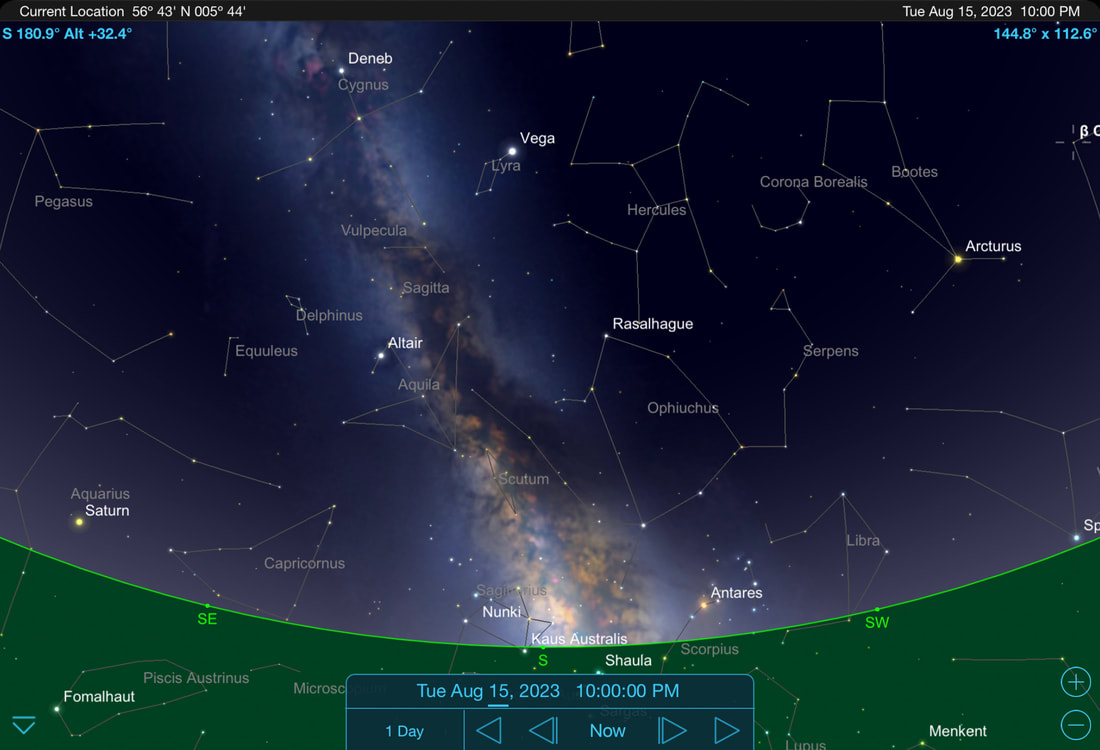

The Autumnal Equinox also paves the way for increased chances to see aurora borealis displays. According to NASA, the equinoxes are prime time for Northern Lights, because the geomagnetic activity that causes them is more likely to take place in the spring and autumn than in the summer or winter. In addition, we tend to have more clear nights in spring and autumn so this, combined with more geomagnetic activity, may be the reason why I tend to have captured most of my Northern Light images in September/October and March/April. Finally, if you do want to catch a glimpse of the “Merry Dancers”, be sure to keep an eye out for “aurora alerts” on the web and on social media. Good sources for forecast and alerts are AuroraWatch UK, Glendale Skye Auroras and Aurora Research Scotland. It’s now August and a few weeks since the Summer Solstice, so you should be noticing it getting dark earlier at night and the stars beginning to appear from about 10pm. Find out how to use the Summer Triangle to navigate your way around them and to also find the cloudy core of the Milky Way. Also find out the best times to look for the two full Supermoons we have this month and for when to watch for shooting stars from the Perseid Meteor shower. The ConstellationsWith sunset now at around 9:00 pm, the stars and the constellations will become visible from about 10:00 pm onwards. As with July, the best way to navigate your way around the night sky is to use the Summer Triangle, which is made up of the three bright stars of Vega, Altair and Deneb. Start off by finding Vega, a bright white star which will be directly overhead. Next is Altair, which you will find halfway between Vega and the southern horizon. Finally, there is Deneb, which will be almost directly above Altair and across from Vega. Once you have found the Summer Triangle, you can now start to look for some constellations. There’s Cygnus the Swan, which is also known as the Northern Cross. It is a large cross-shape with Deneb at the top, marking the tail of a swan which flies down the Milky Way with outstretched wings towards Sagittarius (the Archer) which will be low down on the southern horizon. It’s not a particularly bright constellation, so you’ll need a good clear night and to be far away from any light pollution to see it. When you trace a line between these two constellations, you should be able to make out the Milky Way’s cloudy core, which is the dense and bright region at the centre of our galaxy and home to around 10 billion stars. It will be visible for about two hours after sunset, before dipping below the horizon at around midnight.

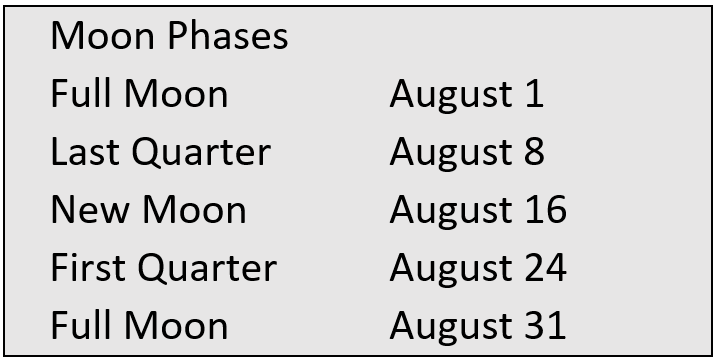

Although most of what to see is in the southern night sky, there are a few notable things to see if you look north. In the north-west, you will find the familiar shape of The Plough and you can use its two right hand stars to point towards Polaris (the Pole Star or North Star), which is always in the same position in the sky To the right of Polaris, you’ll see the W-shape of Cassiopeia, the constellation that represents the fabled vain queen of the same name. At this time of year her husband, king Cepheus, is high in the sky, though his stars are nothing like as bright as those of his beautiful wife. Below Cassiopeia are the stars of Perseus, after which the Perseid meteors are named. These meteors will peak on the night of 12-13 August, and you can find out more about them below. Finally, low down and below Perseus is Capella, the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) and the sixth-brightest star in the night sky. The MoonWe start the month with the first of two full moons when the Moon becomes 100% full at precisely 7:31 pm on 1 August. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 31 July-1 August, 1-2 August, and 2-3 August. It will rise in the south-east at around 10:00 pm on 31 July, then at around at around 10:30 pm on 1 August and at around 10:45 pm on 2 August. Also, on the nights of 1-2 August and 2-3 August the Moon will be very close to Saturn. This full Moon will pass Earth near to the time it is closest to us in its elliptical orbit, making it a supermoon, or a Sturgeon Supermoon. It is the second of 4 supermoons we have this year with the others occurring on the following dates:

The last quarter Moon (a half-moon) is on 8 August. It will spend the night very close to Jupiter as it travels from east to west. The new Moon (no moon) is on 16 August. This means that a few of days before, on 14 and 15 August, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting in the north-east before sunrise. This will be from about 3:30 am to 4:30 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 18 and 19 August, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 24 August. You will find it in the southern western sky, sitting close to Antares and it sets at around 10:30 pm. Unusually, on the night of 30-31 August, a second full Moon, or Blue Moon, will make an appearance. This name does not refer to the Moon's colour, as the Moon usually appears in shades of grey or white. Instead, it refers when two full moons happen within a single calendar month, with the second being called a blue moon. This full Moon will also be a supermoon, making it a Blue Supermoon. It becomes 100% full at precisely 2:35 am on 31 August. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 30-31 August, 31 August-1 September, and 1-2 September. Rising in the east-south-east at around 9:00 pm on each of these three nights, it will be the closest, biggest, and brightest full supermoon of 2023 and a sight well worth looking for. The PlanetsSaturn is visible in the southern sky all night long this month and because it reaches its closest point to Earth on 27 August, it will be shining quite brightly. If you look at it through binoculars or telescope that magnify by about 40 or 50 times, you be able to see its famous rings and its biggest moons. The largest, Titan, is enormous. In fact, it’s 40% more massive than the planet Mercury and 80% more massive than our own moon. To the left of Saturn, you will find Neptune, which is also above the horizon all night long. In contrast to Saturn, it will be quite faint, and you will need a telescope to pick it out from below the stars of Pisces on the southeastern horizon. Jupiter rises in the east at around 11:00 pm, shining brightly and dominating the night sky as it does so. If you look at it through binoculars, you’ll see its four largest moons. They are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and are known as the Galilean moons. Uranus will follow Jupiter, rising about quarter an hour later and may be just visible to the naked eye. Venus disappeared from the evening sky towards the end of last month and reappears in the dawn sky in the last week of this month. Rising at around 5:00 am, the Morning Star will be shining about twice as bright as Jupiter and will be the brightest thing in the night sky, apart for the Moon. Mercury and Mars are lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersAfter a few months’ absence, you’ll be able to see some shooting stars because the number of meteor showers is now on the increase. In fact, August can be a great month for spotting shooting stars because the peak of the annual Perseid Meteor Shower is on the 12-13 August. With the new Moon falling on 16 August, it should be a good year for seeing the Perseids because the Moon will only be a thin crescent and not too bright, so it won’t affect the show too much.

It is called the Perseid Meteor Shower because the radiant (the area of the sky where the meteors seem to originate) is located near the constellation of Perseus and although you can see them throughout the night, you will see more if you wait until this radiant is high in the night sky. This is usually from about midnight until dawn, so watch then to maximise your chances of spotting some shooting stars. Finally, when watching for shooting stars, give yourself at least an hour of observing time, because they will come in spurts, interspersed with lulls. Also remember that your eyes can take as long as 20 minutes to adapt to the darkness of night, so don’t rush the process. If you are patient, you may see up to 60 meteors per hour as the shower’s peak approaches. It’s July and after the summer solstice, so the night sky is beginning to get dark again with the stars and the Milky Way becoming more and more visible as the days pass. You should be able to see its cloudy band of stars passing through Deneb and in between Vega and Altair, the three stars than make up the Summer Triangle. We have the first this year’s four supermoons with this month’s Buck Supermoon and Venus is reaches its brightest before disappearing from view in the second half of the month. Finally, you may be lucky enough to spot noctilucent clouds, ghostly whispers of light shimmering in the all-night twilight in the hours after sunset. The ConstellationsIt’s now after the Summer Solstice so it will begin to get dark at night again and with sunset at around 10:00 pm, you should see the constellations emerging from about 11:00 pm onwards. Also, at this time of year, we begin to see the Milky Way again and at the end of the month, this home to 200 billion stars will be visible from around 11:00 pm because it’s cloudy core will be above the southern horizon then.

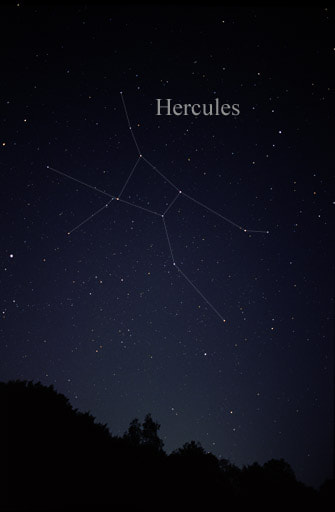

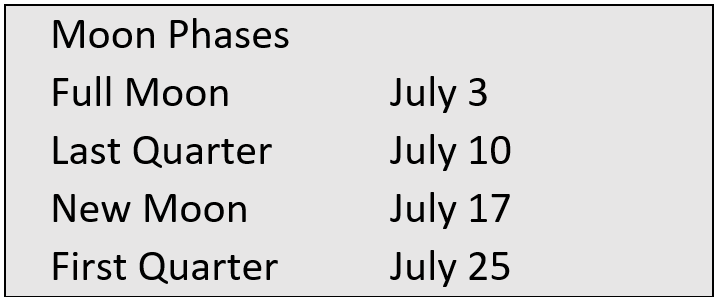

Above Ophiuchus, is the quadrilateral of stars known as the Keystone because of its wedged shape. This is the most recognisable part of the Constellation of Hercules, named after the Roman mythological figure who was known for his strength and numerous far-ranging adventures. The constellation is best known for its great globular cluster of stars, M13, and has a lesser globular cluster, M92, nearby. At one time, the globular cluster M13 was known as ‘The Great Hercules Cluster’. It is the brightest globular cluster in the northern hemisphere and is visible to both the naked eye and binoculars. It contains more than 300,000 stars and is 25,200 light-years from Earth. To find it, look about two thirds of the way up the right-hand side of the Keystone using a small telescope and you should see what looks like a circular misty patch. This is this is the star cluster and if you use a larger telescope, some of the individual stars will be visible. To the east of Scorpius, and just above the horizon, you will find the constellation Sagittarius (the Archer). This is not a particularly bright constellation, so you’ll need a clear night and be far away from any light pollution to see it. If you do spot the stars of Sagittarius, you will see that they form a sort of teapot shape. The handle of the teapot represents the upper body of the Archer, while the curve of three stars to the right are his bent elbow. The spout of the teapot is the point of an arrow which is aimed at Scorpius, the fearsome celestial scorpion. Sagittarius is rich in star clusters and nebulae, some of which you can see with binoculars on a night when the southern horizon is really clear. Above the spout of the teapot is the Lagoon Nebula, a giant interstellar cloud that’s visible to the naked eye. Near to it and visible with a telescope is the three-lobed Trifid Nebula, while above Sagittarius and in the Milky Way, you will find a bright patch of stars called the Sagittarius Star Cloud (M24). Above this, is the Omega Nebula, which is considered to be one of the brightest and most massive star-forming regions of our galaxy. Going back up to Vega, you’ll see the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre), of which Vega is the brightest star. Below Vega, you will see the constellation’s 4 other main stars, which form a small parallelogram. To its upper left is an interesting double star, Epsilon Lyrae. Some people can see this as a double star with the naked eye, but binoculars will show it well. If you use a telescope with an aperture larger than about 75 mm, you will be able to see that each of the two stars are themselves double stars. For this reason, some people refer to Epsilon Lyrae as the “Double Double”. The MoonWe start the month with an almost full Moon that becomes 100% full Moon at precisely 2:48 am on 3 July. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 1-2 July, 2-3 July, and 3-4 July. It will rise in the south-east at around 9:30 pm on 1 July when it will be close to Antares. After that, it will rise at around 10:45 pm on 2 July and at around after 11:30 pm on 3 July.

A full moon happens when the Moon (in its monthly orbit) is on the opposite side of Earth from the sun. A full supermoon happens when the full Moon happens at, or near to the time the Moon is closest to us in its elliptical orbit. To see what closest means, you can compare these Moon distances to the average Moon distance of 238,900 miles (384,472 km):

The new Moon (no moon) is on 17 July. This means that a few of days before, on 15 and 16 July, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting in the north-east before sunrise, which will be about 4:45 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 19 and 20 July, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. On these days, it will be close to Venus, Mercury, Regulus and Mars. The PlanetsVenus has been blazing away in the evening sky over the last few months and it reaches its maximum brightness on 9 July. It sets at around 11:15 pm, so look out for it before then if you want to see it. It will pass the Praesepe star cluster on 13 July and this sight will be well worth observing through binoculars or a telescope. As the nights pass, Venus will drop rapidly into the twilight glow and will have disappeared from view by the end of the month. At the beginning of the month, a considerably fainter Mars can be seen to the upper left of Venus. Over the past few months, the Evening Star and the Red Planet have been moving steadily closer together, being only 3.5 degrees apart in the first week of the July. However, as Venus drops towards the horizon, Mars is moving the other way, following a path beneath Leo before setting at around 11:00 pm. Mercury will appear to the lower right of Venus form about 15 July and will move upwards towards Mars as the month progresses, becoming easier to see as it does so. Look out for it before it sets at around 10:00 pm. While Mars, Mercury and Venus are setting over in the west, take a look over to the east and you will see Saturn rising at about 11:00 pm and spends the night crossing the southern sky in the constellation of Aquarius. It will be shining reasonably brightly, so you should be able to make it out when it is just above the Moon on the night of 6-7 July. Neptune will rise in the east at about 0:30 am, while Jupiter will be clearing the horizon at about 1:30 am. This giant planet will be shining very brightly just beneath the constellations of Aries and Triangulum, and it will be very close to the Moon on the morning of 12 July. Uranus will follow Jupiter, rising about half an hour later at 2:00 am and may be just visible with the naked eye. Meteor ShowersJuly sees the number of meteors increasing and it may be possible to spot some shooting stars from the alpha Capricornid and the delta Aquarid meteor showers. They peak around 30 July, just two days before a full Moon, so viewing conditions will be poor and only the brightest meteors might be visible. Dark, moonless skies are always best for seeing meteors. It will be best to wait until the Perseid Meteor Shower in August for our next good show. Radiating from the constellation of Perseus, it will be active between 17 July and 24 August and will peak on the night of 12-13 August. With the new Moon falling on 16 August, it should be a good year for seeing them because the Moon will only be a thin crescent and not too bright, so it won’t affect the show too much. If you do want to look for the Perseids, then they will be at their best on the few hours before dawn on 14 August when the radiant point is at its highest in the sky. Noctilucent CloudsIn the 8 or so weeks either side of the Summer Solstice, which was on 21 June, the Sun gets to no more than 10-15 degrees below the horizon and full darkness does not occur at any point during the night. During this time you may be lucky enough to spot noctilucent, or “night-shining” clouds.

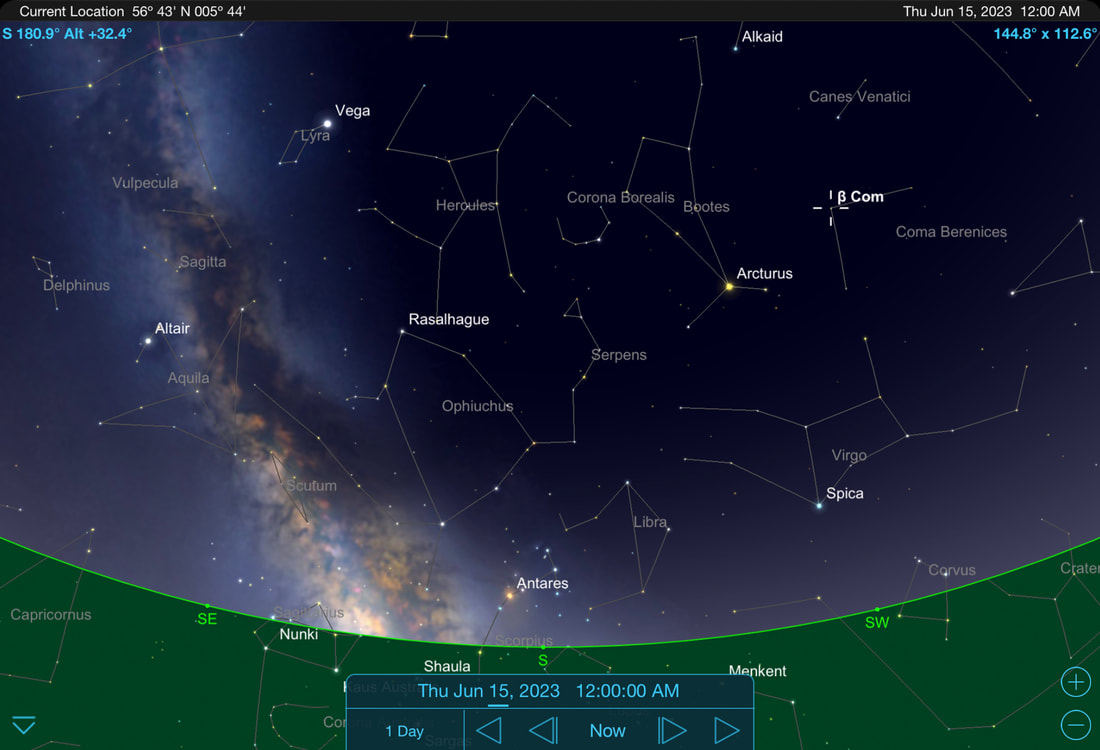

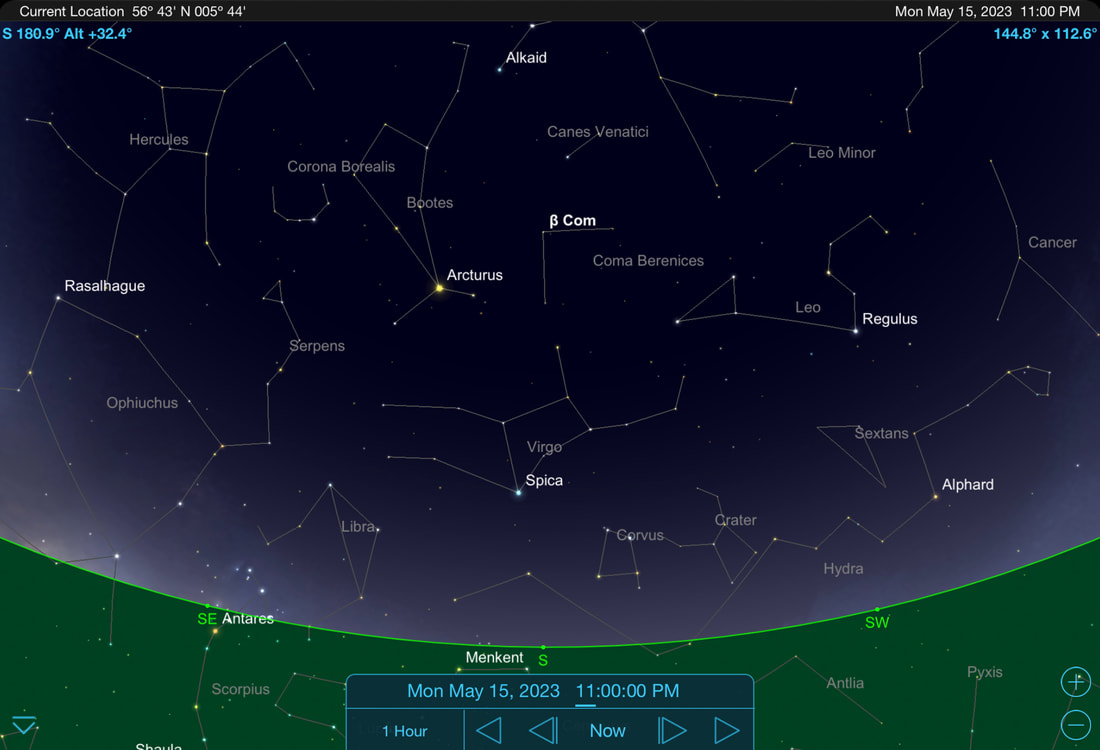

These clouds become visible in the north to north-west sky as darkness falls and just as the brightest stars become visible. They have the appearance of ghostly whispers of light shimmering in the all-night twilight and are usually set against a pearly-blue sky. Forming in the middle atmosphere, or mesosphere, roughly 80 kilometres (50 miles) above Earth's surface, they are thought to be made of ice crystals that form on fine dust particles from meteors and volcanic activity. These ice coated dust particles then reflect the light that the sun projects high up into the sky, when it is between 6 to 16 degrees below the horizon, to create an illuminated cloudy veil in the northern sky at latitudes between ±50° and ±70°. They are first known to have been observed in 1885, two years after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, but it remains unclear as to whether their appearance had anything to do with the volcanic eruption or whether their discovery was due to more people observing the spectacular sunsets caused by the volcanic debris in the atmosphere. June is the month of the Summer Solstice and the Longest Day, so night sky never quite gets dark and it’s not the greatest for spotting faint stars. However, there are 2-3 hours when you can spot the Summer Constellations that are up in the southern night sky just now and you can use the four bright stars, Arcturus, Antares, Vega and Spica to find your way around them. Also, Venus dominates the evening sky, playing its part as the Evening Star by shining brightly in the western sky until it sets at around midnight. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 10:00 pm, so the stars and the constellations start won’t become visible until about 11:30 pm and with sunrise at about 4:30 am, it means that you only have about 2-3 hours to spot them. In fact, it never really gets dark, but it is possible to spot the Summer Constellations that are up in our southern sky just now. Unlike the few big and bright Winter Constellations, these Summer Constellations are more numerous, smaller, and fainter, but you can use four bright stars that are easy to find to navigate your way around them. These stars are Arcturus, Antares, Vega and Spica.

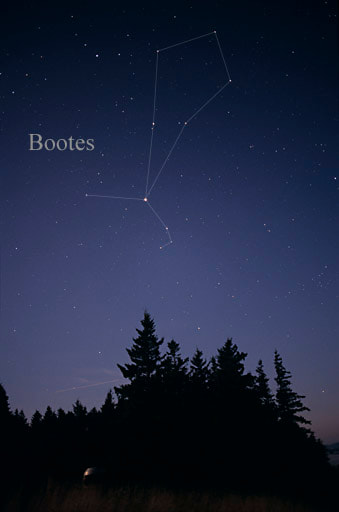

Above Scorpius, you will find Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). It is a large constellation, which straddles the celestial equator, and it is commonly depicted as a man grasping a snake. This snake is represented by the constellation of Serpens (the Serpent), which is immediately to the west of Ophiuchus. Above Serpens, you’ll find the semi-circular constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown), which is made up of 4 bright stars that represent the crown of Ariadne, daughter of King Minos in Greek mythology, who helped the hero Theseus kill the Minotaur and find his way out of the labyrinth in which the creature lived. High up in the south-eastern sky, you will find Vega, the brightest star in the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre) and the fifth brightest star in our night sky. Vega acts as the guide star to the Keystone, a rectangle of four stars in the constellation Hercules, the fifth largest constellations in our night sky. To find the Keystone, trace a straight line from Vega and towards Arcturus. You will find it about one third of the way along this line. The Keystone represents the body of Hercules and is home to M13, the Great Global Cluster, a bee-like swarm of a third of a million red giant stars. It is one of the brightest globular clusters and although it is visible to the naked eye, it will be easier to see when using binoculars or a small telescope. The Moon

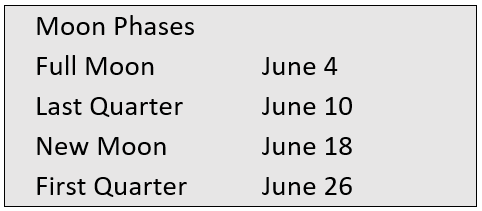

In Colonial America, this full Moon was referred to as the Strawberry Moon because this was when the red strawberries ripened there. Europeans have dubbed it the rose moon, while other cultures named it the hot moon because it occurred at the beginning of the summer heat. The last quarter Moon (a half-moon) is on 10 June, and on the morning of 14 June, you will find it close to Jupiter. The new Moon (no moon) is on 18 June. This means that a few of days before, on 15 and 16 June, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the east before sunrise, which will be about 4:30 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 19 and 20 June, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. Then, on the evening of 21 June, a slightly thicker crescent Moon will be higher up in the western sky, sitting above to the right of Venus. The Moon will be higher still on 22 June, having moved above and to the left of Venus and a feint Mars will be in between the two of them. We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 26 June, and you will find it in the southern western sky, sitting beneath the constellation of Virgo. The following night, on 27 June it will have moved a little to the left to sit very close to Spica. The PlanetsVenus once again dominates the evening sky, and you will see it shining brightly in the western sky as darkness falls. Playing its part as the Evening Star, it sets at around midnight and will be shining far brighter than anything else in the night sky, except for the Moon. It reaches its greatest separation from the Sun on 4 June and on 13 June, it passes very close to the star cluster Praesepe and will be a sight well worth observing through binoculars or a telescope. A considerably fainter Mars will also be seen in the western sky as darkness falls. You will find it slightly to the left of Venus as it follows the Evening Star to drop below the horizon a little after midnight. On 2 June it will appear to lie in the middle of the swarming stars that make up Praesepe, the Beehive Star Cluster. Mars crosses from Cancer into Leo around 21 June, the day of the Summer Solstice when it will also be near to Venus and a crescent Moon. The next planet in the night sky will be Saturn, which rises at around 1:00 am and you will find it very close to the Quarter Moon on 10 June. Neptune will rise in the east at about 1:30 am, while Jupiter will be clearing the horizon at about 3:30 am. This giant planet will be in Aries. The crescent Moon right next to it on the morning of 14 June. Uranus reappears in the morning sky at the end of the month, rising at around 2:30 am but it will be very dim and difficult to see. Mercury is lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersJune is a not a good month meteor showers because most of them occur when it is daylight just now. We need to wait until the Perseid Meteor Shower in August for our next good show. Radiating from the constellation of Perseus, it will be active between 17 July and 24 August and will peak on the night of 12-13 August. With the new Moon falling on 16 August, it should be a good year for seeing them because the Moon will only be a thin crescent and not too bright, so it won’t affect the show too much. If you do want to look for the Perseids, then they will be at their best on the few hours before dawn on 14 August when the radiant point is at its highest in the sky. Summer SolsticeThis year, the summer solstice occurs on 21 June at 14:58 GMT (15:58 BST) and is the exact moment when the North Pole is at its maximum tilt towards the Sun. However, many people refer to it as the “Longest Day” because it is the day when the number of hours of daylight are at their maximum and the number of hours of night are at their minimum. This is because it is the day when the Sun rises at its closest to north-east, reaches its highest position in the sky at noon and then sets at its closest to north-west. For instance, on 21 June this year, our sunrise here on the Peninsula will be at 4:27:33 am and our sunset will be at 10:22:20 pm, giving us 18 hours, 5 minutes and 13 seconds of daylight. On June 20, our hours of daylight will be 5 seconds less and on June 22 they will be 3 seconds less.

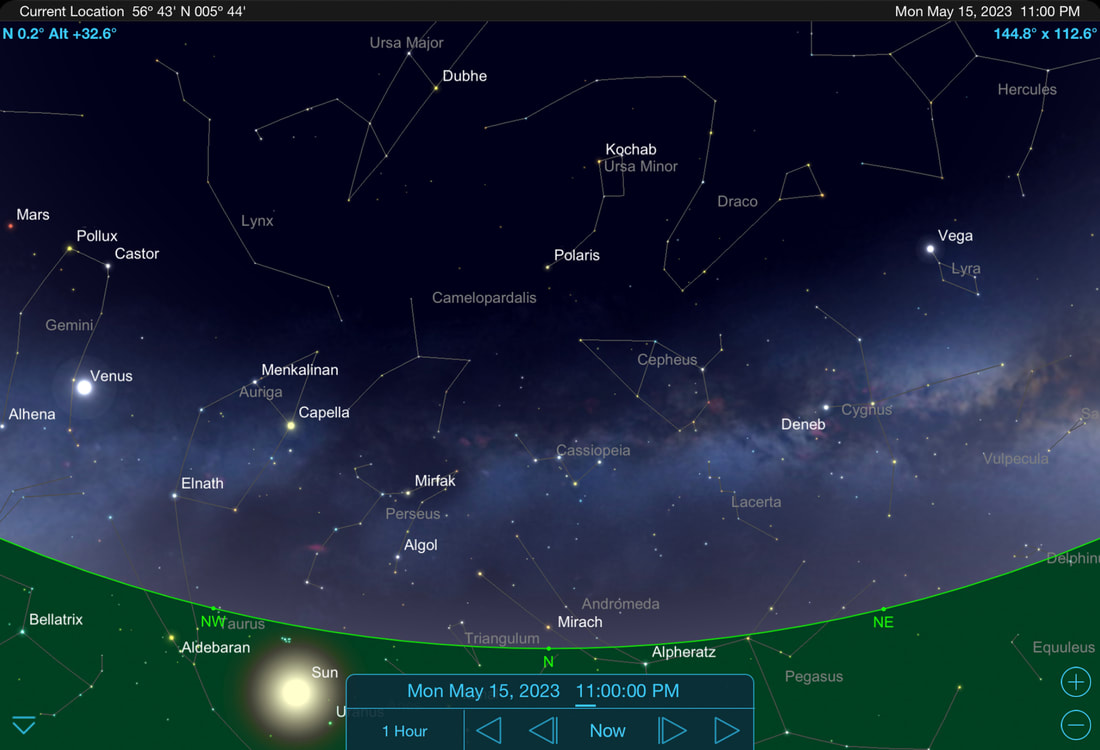

Even though May brings long days and short nights, there is still plenty for us to see if we stay up late or even get up early. You’ll find the constellation of Virgo in the southern night sky. It is home to the Virgo Cluster, which contains over 2,000 individual galaxies, some of which are the brightest galaxies in our night sky, so grab a telescope and have a look for them. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 9:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 11:00 pm onwards. If you look in the south-western sky at that time, you will see the constellation of Leo (the Lion). It was due south last month but has now been replaced by the constellation of Virgo (the Maiden).

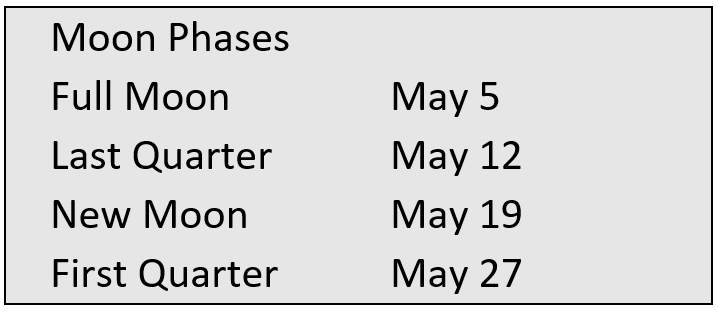

Virgo is home to a large cluster of galaxies known as the Virgo Cluster. This Cluster contains over 2,000 individual galaxies, 11 of which are Messier objects that will be visible to anyone using a reasonable astronomy telescope. All these Messier objects are galaxies and the most notable of these is M104, the Sombrero Galaxy. This edge-on spiral galaxy has a dark dust lane running across its centre, giving it the appearance of a sombrero hat. Other notable galaxies are M49, M58 and M61. M49 is an elliptical galaxy and is the brightest galaxy in the Virgo Cluster, M58 is a beautiful barred spiral galaxy and one of the brighter galaxies in the Virgo Cluster and M61 is a face-on spiral galaxy that is one of the largest galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. Below Virgo is Corvus, the Crow. It is reasonably easy to find as it is a distinct, almost square set of stars right down on the horizon. Above Virgo, you will find Boötes (the Herdsman) and its brightest star, Arcturus. This star is easy to spot as it is the fourth brightest star in the night sky and has a noticeable golden tinge. It is part of the Spring Triangle asterism, which is formed by drawing lines from Arcturus to Spica, Spica to Regulus and Regulus back to Arcturus. Below and to the left of Virgo is Libra (the Scales), a very faint constellation with its main claim to fame being that it is the only constellation in the zodiac which doesn’t represent an animal. The MoonWe start the month with a waxing Moon that becomes 100% full Moon at precisely 6:34 pm on 5 May. This means that it will appear full on the nights of 4-5 May, 5-6 May, and 6-7 May. It will rise in the south-east at around 8:00 pm on 4 May, at around 9:30 pm on 5 May and shortly after 11:00 pm on 6 May.

The new Moon (no moon) is on 19 May. This means that a few of days before, on 16 and 17 May, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the east at sunrise, which will be about 4:30 am. Alternatively, a day later, on 20 May, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. On the following evening, 21 May, a slightly thicker crescent Moon will be higher up in the western sky, sitting well below and to the right of Venus. The Moon will be higher still on 22 May, having moved to just below and to the right of Venus. On the following evening it will be between Mars and Venus. We have a first quarter Moon (a half-moon) on 27 May, and you will find it high in the southern western sky, sitting beneath the constellation of Leo. Three nights before, on 24 May, it will be sitting just above and to the left of Mars. The PlanetsJust like last month, you will see a brilliantly shining Venus in the western sky as darkness falls. Playing its part as the Evening Star, Venus doesn’t set until well after midnight and it will be shining far brighter than anything else in the night sky, except for the Moon. On 22 and 23 May, you will find it close to the Moon, while on the last few days of the month, it will be close to Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini. You will find Mars high up in the western sky as darkness falls, well above and to the left of Venus, initially in Gemini, but moving to the left of this constellation as the month progresses to eventually find itself in the constellation of Cancer. It will be visible for a good part of the night, before setting at around 1:30 am and on 24 May, it will be very close to the Moon. Once Mars has set, you will need to wait until around 3:30 am to see another planet because that is when Saturn will rise above the horizon. You will find it in the eastern morning sky, sitting in the constellation of Aquarius. The Moon will pass beneath it on 13 and 14 May. Neptune will rise in the east at about 4:00 am, but it will be difficult to see it because this outermost planet is very faint and may be lost in the morning twilight. Jupiter reappears in the morning sky from about the middle of the month. You will find it low down on the eastern horizon at daybreak, shining brightly in-between Pisces and Aries. A crescent Moon will be close to it on the morning of 17 May. Uranus and Mercury are lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersThe main meteor shower in May is the eta Aquariids, which is the result of small pieces of Halley’s Comet burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere. This year it is active between 19 April and 28 May, with the forecast to peak being between midnight and dawn on the morning of May 6, making this the best time to look for them. However, as there is no sharp peak for this shower, but rather a plateau of good rates that lasts a few days, then same time on May 5 and on May 7 will also be best for watching for them. Unfortunately, there is a full Moon on 5 May, meaning that bright moonlight will drown out all but the brightest meteors on these three nights. Given this, it may not be worth staying up until the wee small hours of the morning to try and look for them.

If you do decide to try and do spot some, they will appear to emanate from the constellation of Aquarius (The Water Carrier) at a radiant point near the star Eta Aquarii, although you don’t need to look there to see meteors as they’ll appear across the whole night sky. Start looking for them shortly after 3:00 am because this is when the radiant point is above the horizon. Bear in mind that the higher the radiant point gets in the night sky, the greater the number of meteors you should see. Sunrise is at around 5:30 am, so this gives you an hour or so to spot them. At its peak, on a moonless night, around 10-20 meteors per hour may be spotted. As the days lengthen and the nights shorten there is still plenty to see in this month’s night sky. The winter constellations will gradually disappear beyond the western horizon as the spring constellations of Leo and Virgo dominate our southern sky. Also, after a gap of a few months, shooting stars return in the form of the Lyrids meteor shower, which peaks on the night of 22-23 April. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 8:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 10:00 pm onwards. So, once it is getting dark, look directly above your head and you’ll see the Plough, which is an asterism that is familiar to a lot of people. This makes it an excellent starting point from which to navigate your way around the southern night sky.

Below and to the left of Leo is the constellation of Virgo (The Virgin), with its brightest star Spica sitting down towards the horizon. In some cultures, Virgo is the "Wheat-Bearing Maiden" or the "Daughter of the Harvest” and is depicted holding several spears of wheat in each hand and Spica is one of the ears of grain hanging from her left hand. If you can’t find Spica, try going back up to the Plough and follow the curve of its handle down through the very bright star, Arcturus and then further on down to Spica, which will be low in the sky. Below Virgo, you will see the small constellation of Corvus (The Crow), which ranks 70th in size among the 88 constellations in the night sky. The four brightest stars in this constellation form a square asterism known as the Sail, or the Spica’s Spanker, because two of the stars point the way to Spica. It is an ancient constellation that has been known since the time of the Babylonians. They saw it as a raven, and it was sacred to Adad, the god of rain and storm. To the ancient Greeks, it was a crow sent by Apollo to fetch water. The raven wasted his time eating figs. After returning late, Apollo punished him by throwing him into the heavens. He was also condemned to endure eternal thirst. This is why the crow caws instead of singing like other birds. If you are at a location with little or no light pollution, you may be able to pick out Hydra (The Water Snake), which wriggles along the southern horizon and is the largest constellation in the night sky. Most of its stars are faint, but Alphard, its brightest star, is quite easy to find if you look below and to the right of Leo’s brightest star, Regulus. Alphard is from the Arabic for "the solitary one" as there are no other bright stars near it. You might also be able to pick out the head of the Water Snake. It is an almost square set of four stars about halfway between Regulus and Procyon, the brightest star in Canis Minor, which sits below Castor and Pollux. The Moon

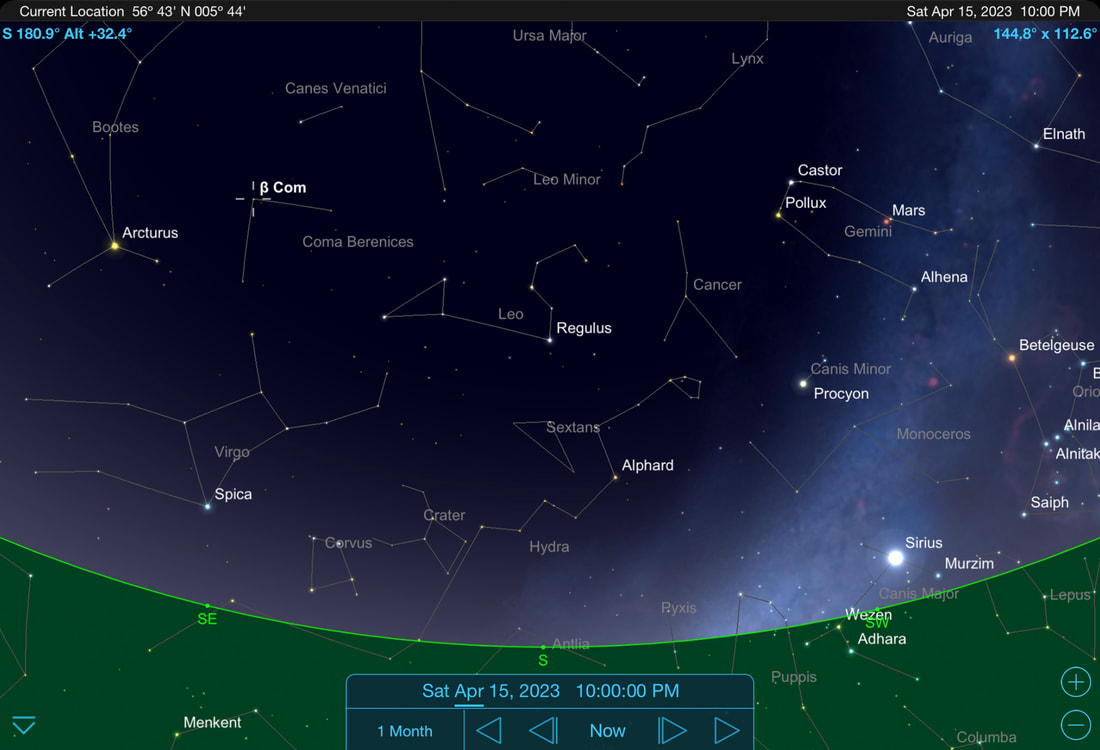

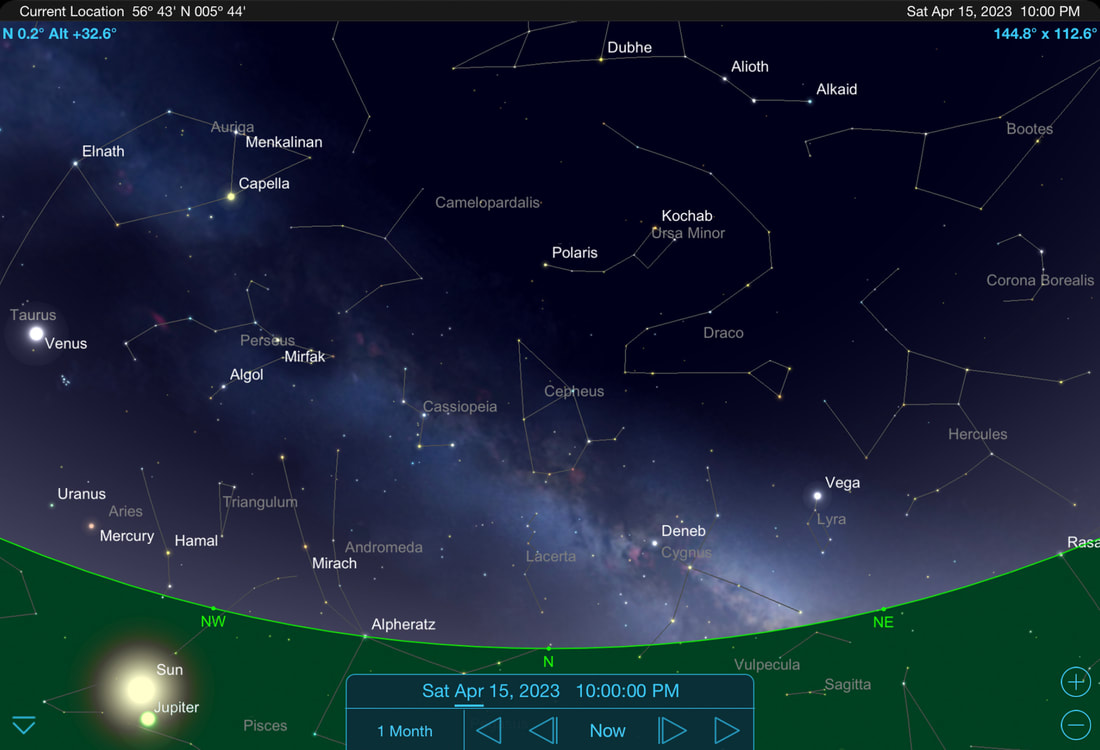

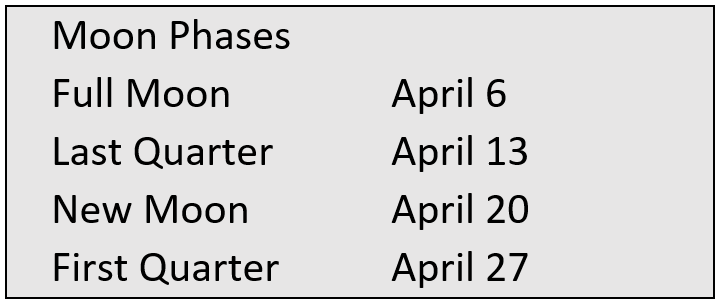

This month’s full Moon is often called the Pink Moon because of the pink flowers – phlox – that bloom in early spring in North America. In other cultures, it is called the sprouting grass moon, the egg moon, and the fish moon. The last quarter Moon is on 13 April and the new Moon (no moon) is on 20 April. This means that a few of days before, on 16 and 17 April, you should see the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the east around sunrise at about 6:00 am. Alternatively, a few days later, on 21 April, you should be able to pick out the thinnest of crescent Moons sitting low in the western sky as the Sun sets. On the following evening, 22 April, a slightly thicker crescent Moon will be higher up in the western sky, sitting below and to the right of Venus. The Moon will be higher still on 23 April, this time sitting just above and to the left of Venus. We have a first quarter Moon (a half moon) on 27 April, and you will find it high in the southern western sky, sitting about halfway between the constellations of Gemini and Leo. A couple of nights before, on 25 April, it will be sitting just above and to the left of Mars. The PlanetsIf, during February, you’ve been looking over to the western horizon as darkness falls, you will have spotted a brilliantly shining Venus getting higher in the sky. This month, the Evening Star doesn’t set until midnight, so it appears really bright against the pitch-black night sky. On 11 April, Venus passes to the left of the Pleiades while in the middle of the month, you will find it near Aldebaran and then on 22 and 23 April, you will find it close to the Moon. Mercury will be just above the western horizon as darkness falls, but as it will be quite faint, it would be best looked for using binoculars or a telescope up to around 10:00 pm, which is when it sets. It will become fainter and fainter as the month progresses before finally disappearing in the brightness of the Sun during the third week of the month. Uranus is sitting not that far from Mercury, but as it is much, much fainter, it will be very difficult to spot. It too will disappear into the dusk glow from the Sun during the second half of the month. Mars is visible for a good part of the night, before setting at around 2:30 am. You will find it high up in the western sky, sitting in the constellation of Gemini. The Moon will be close to it on 25 April. After disappearing for a month, Saturn returns, but this time in the morning sky. You’ll find it rising over in the east at around 5:00 am, moving upwards as the month progresses. Jupiter and Neptune are lost in the Sun’s glare this month. Meteor ShowersAfter several months without any major meteor showers, we have the Lyrid meteor shower this month. It starts on 15 April and reaches its peak on the night of 22-23 April, when its dust particles that originate from the comet Thatcher hit our atmosphere are expected to produce around 15-20 meteors per hour. However, a good number of meteors can usually be seen on the night before and the night after the peak. This year, the peak just two days after a new Moon, making it a great year for spotting shooting stars because the sky will remain dark pretty much all night.

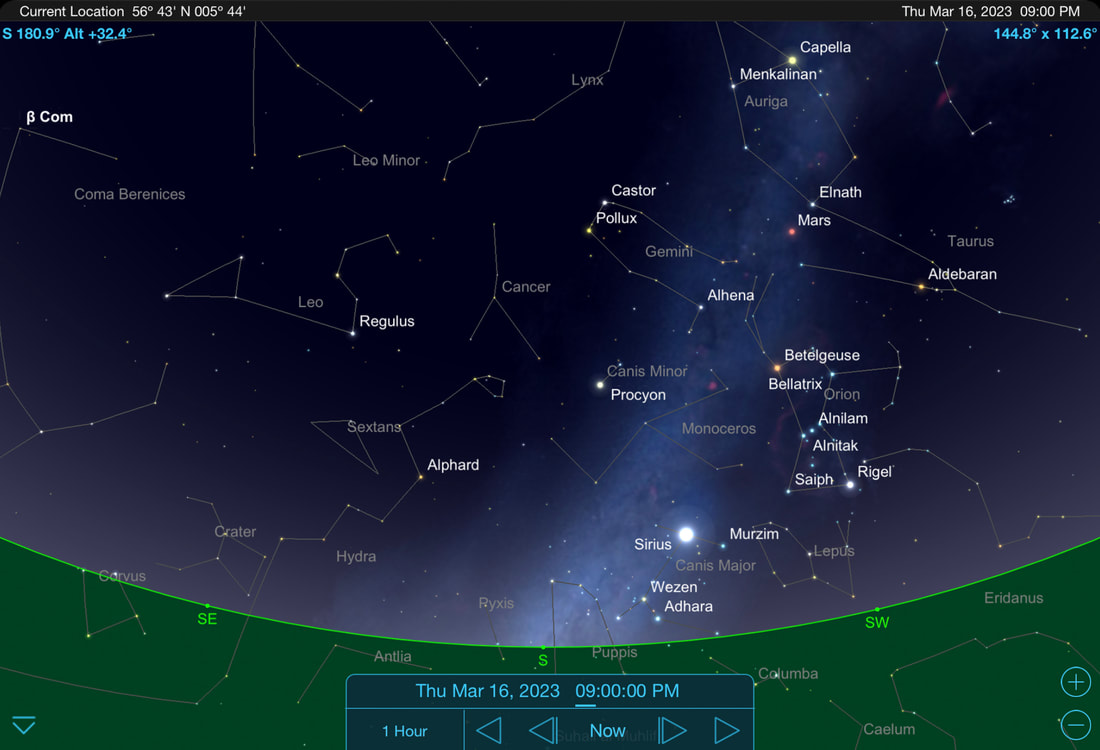

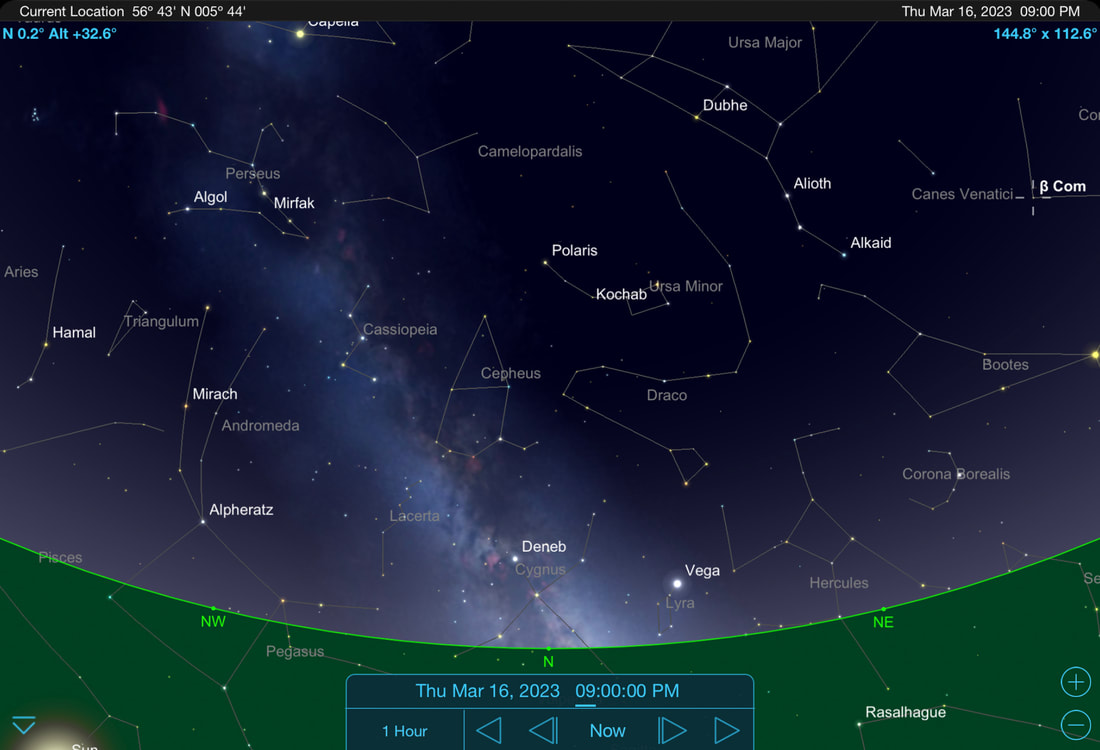

The meteors will appear to emanate from the constellation of Lyra (The Lyre) at a radiant point near Vega, the constellation’s brightest star and the fifth brightest star in the night sky. You will find Vega over in the north-eastern night sky from 10:00 pm, although you don’t need to look there to see meteors as they’ll appear across the whole night sky. Start looking for them from about 10:00 pm as that is when the radiant point is above the horizon and bear in mind that the higher the radiant point gets in the night sky, the greater the number of meteors you should see. Spring arrives this month, with the Spring Equinox occurring on 20 March. On that day, the Sun rises at about 6:25 am due east and sets at about 6:25 pm due west. From then on, the nights get shorter and the days get longer. British Summer Time (Daylight Saving Time) starts on 26 March, so it gets dark a lot later in the evening. However, don’t be put off by the nights becoming shorter because there is still much to see, with the bright winter constellations still being visible and the constellation of Leo (The Lion) coming in to view. Also, it’s a great time of the year to see the Northern Lights and the night sky’s most elusive phenomenon, Zodiacal Light. Finally, we have the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter on 1 March when the two planets will pass within the width of a full Moon of each other. The ConstellationsThis month, the sun sets around 6:30 pm and the stars and the constellations start to become visible from about 8:30 pm onwards. If you look south, you will still see the winter constellations of Orion, Taurus, Auriga and Gemini which I described in the night sky guide for last month. When looking for them, do bear in mind that they will have moved a little bit to the west. Also, you will now be able to see some of the spring constellations coming into view, with the most significant of these being Leo, which will be high up in the south-east sky.

Looking North, the thing to bear in mind is that the constellations you see do not change from month to month, it is only their orientation that changes. You can find the seven stars of the Plough up in the north-east and you can use its two right-hand stars to find the Pole Star, Polaris, which is always in the same position in the sky. Just follow the line between them for about five times its length and you’ll arrive at it. Once you’ve found Polaris, you can use it to get your bearings on any night but bear in mind that all the northern constellations rotate around it in an anticlockwise direction and therefore change their position. It is also worth noting that Polaris is not that bright, with it being about the same brightness as the stars of the Plough. Its significance comes from it being directly above our North Pole. It’s just by chance that this millennium it happens to be very close to the pole of the northern sky, but there is a slow movement of the sky over the centuries that shifts the position of the stars, and 1000 years ago it wasn’t as close as it is now. The constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) was pretty much overhead last month and is now starting to sink down towards the western horizon but it’s still high up. It’s in the shape of a pentagon, with Capella, one of the brightest stars in the sky, at its northern tip. Next to Capella is a triangle of three stars which, though much fainter, makes the whole constellation very recognisable. Below Auriga is the constellation of Perseus who, in Greek mythology, beheaded the Gorgon Medusa for Polydectes and saved Andromeda from the sea monster Cetus. Also, below Perseus, you may be able to pick out the W-shape of the constellation of Cassiopeia, so named after the vain queen Cassiopeia in Greek mythology, who boasted about her unrivalled beauty. The Moon