|

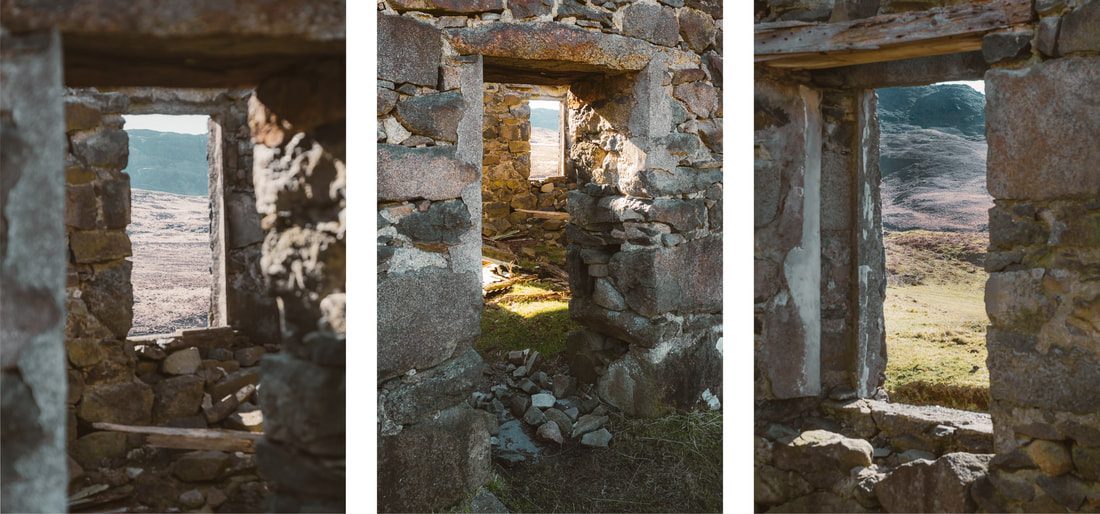

Photography is not always about taking photos and April was a case and point. I spent a large proportion of the month off the Peninsula, so only managed to get a couple of opportunities to be behind the viewfinder and unfortunately, they did not yield much that I was happy with. Fortunately, I was able to find time to sort through, sequence and edit a set of images that I had taken on a bright spring day last year when I visited the abandoned crofting township of Glendrian at the west end of Ardnamurchan. It is a fascinating and somewhat poignant place to be. It is a “thin place” where you can feel a heightened awareness of being very close to the past while you wander through the ruins of its abandoned buildings, the last of which was vacated in the early 1940s. Glendrian sits on the low land within the circle of hills that form the crater of the long extinct volcano that you drive through on your way to the beach at Sanna. It is about 2 kilometre walk from where you park and the first part of the walk takes you up a short uphill section at the start of an estate track that leads all the way to the settlement. At the top of this short climb, you pass through a kissing gate and from there, the view opens up to the east and you catch your first glimpse of some of the houses sitting beneath the hulking black rocks that form the ring dyke of the volcano. These houses are part of a settlement that is made up various structures, from small round cornered buildings with only one or two windows, through to more substantial gabled buildings with chimney pots and harled exteriors. They are scattered across a large area running roughly south to north along the eastern edge of the ring dyke and, as you wander around them, you often catch glimpses of the sea, which is about another 2 kilometres beyond the settlement. As you get close to the first of the houses, you cross the Allt Nead an Fhìr-eòin, a small river which I assume was the main source of water for those who once lived there. It is such a quiet spot and I found myself sitting there for a while watching the sunlight dance across the rocks beneath the rippling water. The first group of houses, located at the southern end of the settlement, are the most modest and appear to be the oldest. Some sit on their own, isolated in the landscape, while others are built into the hillside and have what look like small byres attached to them. They are also the most ruinous of the buildings, which perhaps suggests that they were the first to be abandoned. Research suggests that this may have happened in the late 19th century when the smaller crofts at Glendrian were gradually merged together to form larger tenancies, resulting in the number of households dropping from ten at the time of the 1861 census to three at the time of the 1901 census. Unlike many of the old crofting settlements in the Scottish Highlands, Glendrian was not subjected to the brutality of the mass evictions of the “Clearances”. Instead, its population was gradually decreased by changes in land management practices, but despite this, it was incredibly poignant to sit on the hillside and watch sheep graze in a place where people once lived. A place that they once called home. By the late 1930s, only two families remained. One of these families was the Hendersons, who occupied a terraced group of buildings that can be found mid-way along the settlement, high up on a piece of relatively flat ground at the base of the ring-dyke of the volcano rises upwards behind it. The buildings are more intact than those to the south, with the apexes of the gable ends of the croft house still standing and harling still visible on some of its external walls. Its last occupants, Donald and Mary Henderson, moved to Kilchoan shortly after their son Angus was born in 1940. Below the Hendersons, lived the MacLachlans, who occupied what is the most significant building remaining in the settlement, a two-storey house which was built around 1871. Although basic by today’s standards, it was far better appointed than the other buildings in the settlement with its chimney stacks at each end serving three fireplaces. Two at one end, ground and upper floor, to provide heat and one on the ground floor at the other end for cooking. This “new house” was first occupied by Allan MacLachlan shortly after it was built, and its last occupants were John MacLachlan and his wife. John died in 1941 and his now widow moved to Achnaha to stay with her nephew, leaving Glendrian abandoned to this day. The house resisted the elements for a good number of years with its roof finally coming down during a storm in 1994 and one visitor reported that the upper floor remained in place until as late as 2009. Just over a decade later, there is not much left of anything that isn’t stone, with the doors, windows, floors and roof now long gone. All that remains are some fragments of the corrugated tin roof and some pieces of timber supports, all of which now lie on the ground on the eastern side of the house after presumably being blown there by the winds of that fateful 1994 storm. After photographing in and around the house, I explored the outbuildings that were attached to it, ending my visit by surveying the expansive view of the volcanic caldera from the elevated position that a once thriving community had occupied. While doing so, I began pondering on how the ruins of nearly twenty buildings remained following the 80 years over which the settlement was gradually abandoned and the just over 80 years since the last occupant left. While doing so, I couldn’t begin to imagine the mixture of emotions that the last occupant might have felt as they closed the door on their home for the last time.

4 Comments

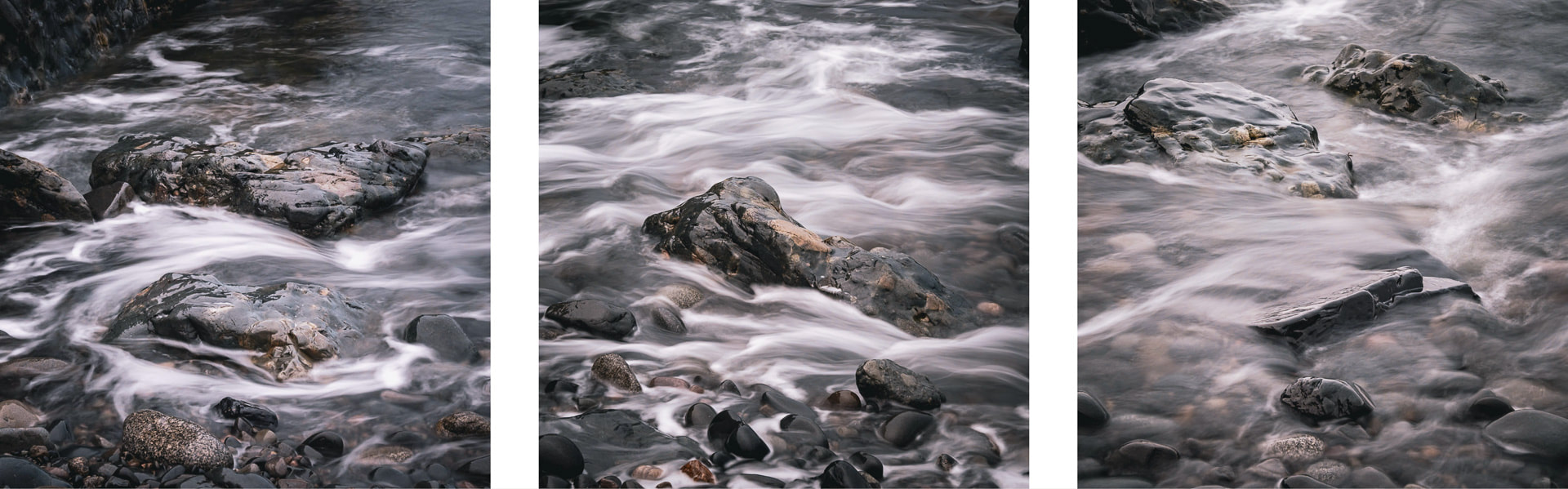

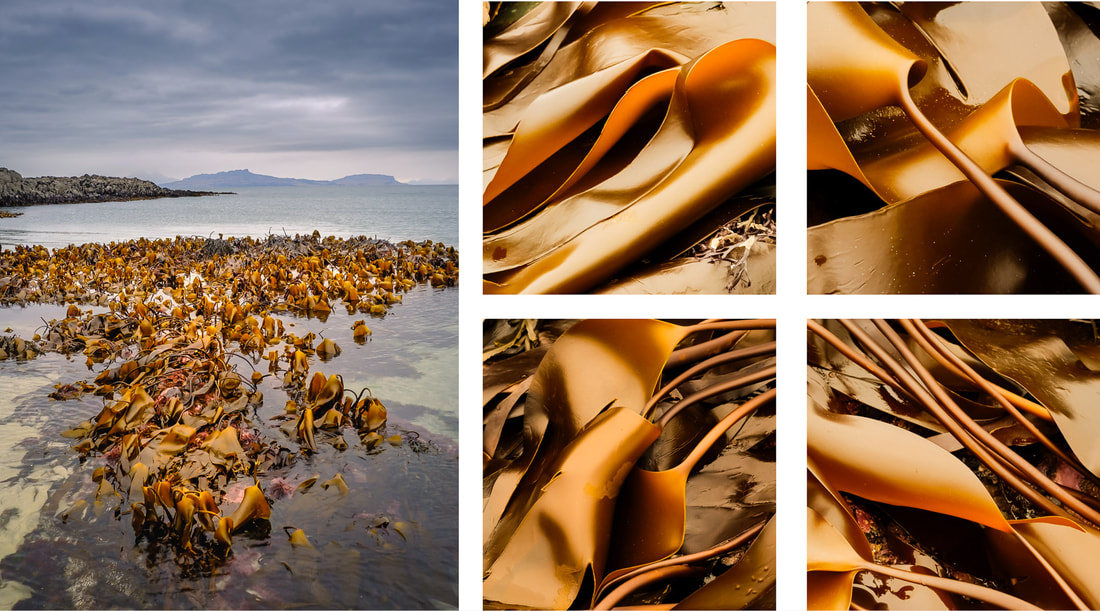

March was quite a busy month photographically, with me visiting numerous places across the Peninsula from Portuairk right over in the west of Ardnamurchan; Fascadale Bay, Kilmory Beach and Swordle Bay on its northern coast; the River Shiel and Castle Tioram in Moidart; and then finally Kinlochaline over in Morvern. However, I’ve decided here to focus on images from two visits that I had to Fascadale Bay. One was at high tide and the other was at low tide, meaning that the nature of the place was very different on each occasion. My first visit to Fascadale was on an afternoon at the start of the month when a high tide brought the sea well up onto the rocks around the sides of the bay. It was a dreich day and shower after shower of fine rain was blowing in from the hills that were to my back while I stood at the edge of the beach and watched the waves wash over a mixture of rounded stones and jagged boulders that made up the foreshore. I stood there for a while, taking in the scene before me and listening to the sound of the sea washing over the boulders before deciding that the conditions were best suited to some long exposure photography. So, I headed down to the water’s edge, set up my tripod and took a few shots of the western side of the bay before pointing my camera downwards to focus on the water that was washing around my feet and the boulders I was standing on. Satisfied with the shots I had taken, I packed up my tripod and filters, put my rucksack on my back and made my way up a steep bank of rounded boulders and away from the sea. Having kept my camera to hand, I took one final photograph of the bay, shooting low and wide to capture some boulders whose colours had been made vibrant by the rain that had soaked both them and me. I returned to Fascadale Bay about a week later, but this time my visit coincided with low tide, rather than high tide. So instead of the sea washing over the boulders that it had been on my previous visit, it was gently lapping on light coloured sand that had been exposed by the receding tide. I walked along the edge of the sand next to the boulders, along to the eastern side of the bay and stood for a moment. Looking northwards out to sea, I could see the Isle of Eigg on the distant horizon and decided to take a photograph of it, using the rocks to the right to lead the eye out towards it. Before making my way down to the waterline, I turned my attention to the pink tinged rocks that were behind me and took a series of images of where they met the sand. When you first look at these rocks, they seem to be well rounded and smooth, but a closer inspection reveals a surface that has been made rough by the plethora of small limpets that covers them. Having finished photographing the rocks, I turned back to face the sea to be met with the distant view of the Skye Cuillin. It was backlit by a warm orange glow and such an enchanting sight that was well worth capturing. I eventually made my way down towards the sea with the intention of photographing the beautiful shapes that the peat and rock grains from the surrounding landscape had formed on their journey across the sand. However, I caught sight of a patch of kelp that had been uncovered by an exceptionally low spring tide and decided to spend some time photographing that instead. I wasn’t disappointed because both the colours and shapes were exquisite. It was as if leaves of gold had been placed in the water. Finally, after photographing the kelp, I turned my attention to the ribbons and strands of peat and rock granules that had created intricate shapes that contrasted against the light-coloured sand. My first find was stone that looked as if it was the seed from which fine fronds of a plant had germinated. It’s amazing that dark granules of sediment being deposited by water flowing past the stone could create such a shape. I continued to explore the beach, finding shapes that were reminiscent of small trees, shapes that were angular and geometric and then numerous light-coloured ridges interspersed with the troughs of dark sedimentary material. Before leaving the beach, I took one final photograph to capture a particular patch of sand that was covered in numerous veins of dark sediment that had been left behind by the falling tide. It was such an exquisite sight, and one that I felt compelled to capture, thus making it a fitting end to my time spent photographing what is an extremely small but feature filled part of Ardnamurchan’s northern coastline.

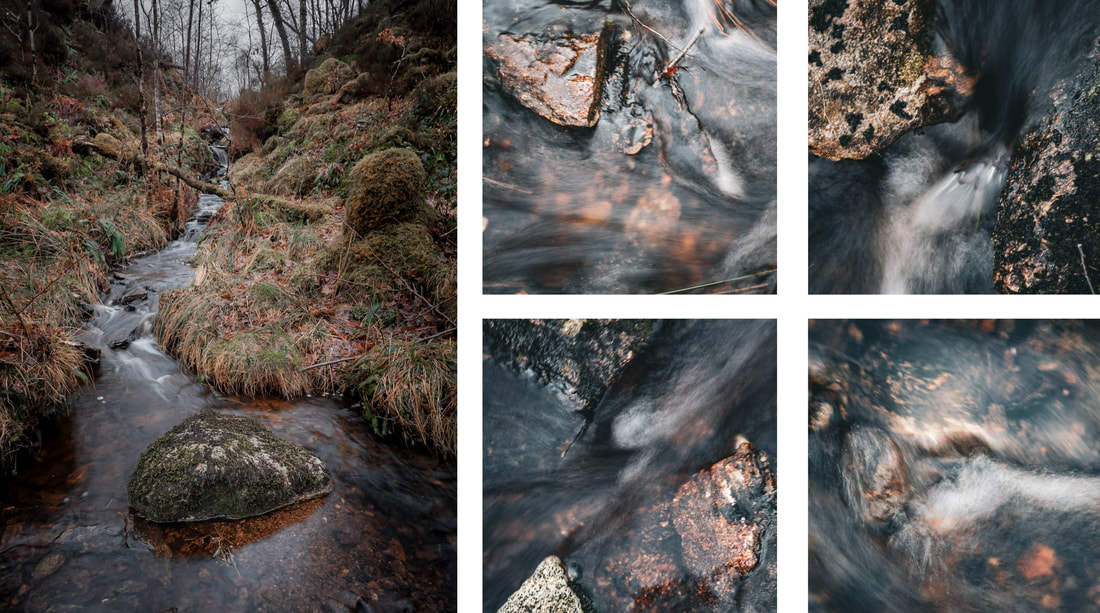

February, the last month of meteorological winter, proved to be less stormy than January but what it lacked in wind was certainly made up in rain. Looking at my weather station, it was the second wettest February I’ve experienced since moving to the Peninsula in 2016, with almost 200mm of rain in the month, and over half of that falling in the first week. The sheer volume of rain falling onto already saturated ground over such a short period of time meant that both the River Shiel and Loch Shiel were as high as I’ve ever seen them. I was keen to record this, so I headed up to the bridge that crosses the River Shiel just to the north-west of Acharacle to see what I could photograph. On the morning I was there, the rain had eventually stopped and the rising sun occasionally shone through the breaks in the cloud that were beginning to appear. This first image I took were of the bridge silhouetted against the warm morning light and I then turned my attention to picking out some of the trees downstream of it, that were sitting submerged in a few feet of water. A couple of mornings later, I returned to Acharacle, but rather than photographing the bridge again, I decided to focus on Loch Shiel and the submerged fences that were in the flooded fields close to the Shielbridge Hall in the centre of the village. I was there just before sunrise, hoping for some colour to appear in the sky but high-level cloud cover prevented this and instead the landscape was bathed in some beautifully subtle, soft and warm light. This was perfect for the shots I ended up taking. Upon finishing exploring the submerged fence posts, my attention turned to the various patches of ice that had formed along the water’s edge as a result of overnight sub-zero temperatures. Indeed, I was very appreciative of my liner gloves and woollen mitts, packed with charcoal hand warmers, which were keeping my fingers warm while the mercury still hovered around the -2°C mark. There were some fascinating wafers of ice suspended above the surface of the loch by tussocks of grass, presumably left because the water level in the loch was falling now that the rain had stopped for a couple of days. As well as these suspended wafers of ice, the curving water's edge near the Shielbridge Hall played host to a myriad of intricately frosted blades of grass that formed the boundary between the frozen field and the frozen loch. They were a joy to photograph. The middle of the month was dominated by misty, grey days which are best described as being “smirry”. You see, “smirr” is an Old Scots word for a delicate form of rain or a misty drizzle that lingers in the air and that’s certainly what we had. On days like that, woodlands are a good place to go for taking photos, so I decided to take my camera on a wander around the 4km loop at Ariundle Oakwood which takes you up the side of the Strontian River and back down through the ancient oaks that can be found there. Despite the greyness of the day, there was still some colour to be found as my eye was drawn to the contrasts between the orange hues of the winter undergrowth, the purple tinge of the bare branches of stands of silver birch trees and the silvery grey of the lichen covered branches off the gnarly oak trees. However, as always, the thing that catches my eye most when I take a walk through the oakwoods is the combination of thick and twisted oak tree trunks and branches surrounded by large and rounded moss covered boulders. There’s something quite enchanting about this sight and I think that it is little wonder that folklore has it that the boulders are home to faeries that live in the woods. My next outing with the camera took me to Sàilean nan Cuileag, a small bay on Loch Sunart, just to the east of Salen. It’s not far from my house, so it is a place I often take the dog for a walk and on the countless times I’ve been there I’ve crossed a small stream that cuts across the path on the way down to the bay. I’ve never paid much attention to it but on this occasion, I stopped and spent some time taking some close-up shots of the water flowing over the red tinged stones that can be found in the streambed. I had never noticed them before, so the experience reminded me of what you can see if you take the time to slow down and really look at something. After photographing the streambed, I continued my walk down to the bay with the intention of photographing the stream as it flowed into the sea at high tide. I took a few shots of the scene I had in my mind, but the dullness of the evening meant that I didn’t get anything I was happy with. Instead, I turned my attention to taking some close-up shots of the trees that fringe the bay. They comprise a mixture of larch and oak, whose bare branches were covered with silvery grey lichen just like those I photographed at Ariundle Oakwood a week or so earlier. From all of the images above, you will see that February has been quite a grey and colourless month, but thankfully as both the end of the month and the end of meteorological winter approached, the weather began to improve and we were treated to a couple of colourful sunsets. During one of these, I was looking eastwards, out of the kitchen window, just as beautifully warm light fell on a snow capped Fuar Bheinn, a 2514-foot-high Corbett that is one of a horseshoe of peaks that circles Glen Galmadale over on Kingairloch Estate. It was such a beautiful sight, so I just had to grab my camera, rush outdoors and capture the scene before the light disappeared as the sun dipped below the hills behind and to the west of me. After this, I stayed by the loch side for a while and watched the colours of the loch, sky and landscape change as the sun set and took the following image which shows the view looking westwards down Loch Sunart from Resipole. This rich orange glow of a late winter sunset was a perfect and spectacular end to a month, which for the most part, had been a dull and grey one.

I’m sitting writing this while the wind is howling outside, the rain is battering off the window of my studio and the sea is being whipped up into a frenzy as yet more stormy weather passes over us here on the shore of Loch Sunart. This type of weather sure seems to have been a feature of the last few weeks, with us seeing no less than three named storms during January. We had storm Henk at the start of the month and storms Isha and Jocelyn at the end of the month. Of the three, Isha had the greatest impact on the UK with it being the most significant wind-storm to affect the UK since storm Eunice in February of 2022. However, for us here on the north-west coast of Scotland it was storm Jocelyn that felt to be the most severe, with wind gusts well in excess of 100 mph being measured in a number of places up this way. As well as these named storm days, there seemed to be many other days on which the weather was just a wild, so this limited the number of times I was able to get out with my camera during January. However, I did venture to the loch shore in front of the house during storm Jocelyn and managed to take the following image while struggling to stay upright as gust after gust attempted to lift me off my feet. Thankfully, in the second week of the month, the sky cleared to bring a spell of extremely still and cold weather. The inordinate amount of rain that storm Henk had dumped on us meant that a layer of fresh water had settled on the surface of Loch Sunart, and it froze to form a layer of surface ice that ran from the head of the loch at Strontian all the way down as far as Glenmore where Ardnamurchan Distillery is located. Having the loch freeze as it did is an extremely rare occurrence, so I decided to spend a few hours one morning to explore as frozen Salen Bay while accompanied by the sound of cracks and bangs from the ice as it shifted on the changing tide. I came away with a number of photographs, including the ones here, which were taken on and around the old stone jetty about half-way down the west side of the bay. The ice had all but disappeared a couple days later and this allowed to safely walk out into Sàilean nan Cuileag, the smaller bay to the east of Salen Bay. It completely empties at low tide and is a place where I frequently walk the dog. When I do, I tend to take my camera because there is often something to photograph there and, on this occasion, I found a perfectly straight high tide mark where white hoar frost contrasted with the black rock that had been revealed by the falling tide. It was such an unusual sight and I just had to capture a few photographs of it before it disappeared. The cold, dry and settled weather lasted about another week before being brought to an end by some of very snowy weather when unusually, successive snow showers covered the loch shore with a white banket that lay all the way down to the sea after each successive high tide for about 3 or 4 days. Unfortunately, the amount of snow that kept falling meant that driving wasn’t to be recommended, so I had to content myself with some photography from the loch shore in front of the house and with some drone photography from above it. However, the house is in a beautiful spot. One that is simply magical during a winter sunrise, and I was happy to be able to capture a little bit of this magic not long after high tide on the morning of 15 January. The snow had just stopped falling and the sun was beginning to rise above the hills of Morvern on the other side of the loch, bringing with it a lovely combination of pastel pinks and blues that were followed some intense bursts of yellows and golds. Winter sunsets at the house can be spectacular too, especially on a perfectly clear evenings such as the one shown here when an intense band of yellow filled the western sky and painted the surface of the loch. Although there is no doubting that such sunsets are an amazing sight, I sometimes prefer photographing in the hour after sunset. Called the Blue Hour, it is when the sky transitions to a serene shade of blue and creates a magical and tranquil atmosphere. So, on this particular evening, I turned the drone to face the other way, waited for the blue to appear and took these images. The image on the left shows the settlement of Resipole with the snow-covered flank of Ben Resipole beyond it and a snow fringed Loch Sunart to its right, while the image on the right was taken looking straight down at the contrast between the snow covered oakwoods, the bare boulders of the loch shore and the deep blue of the loch itself.

|

AuthorHi, I’m Steven Marshall, a Scottish landscape photographer based at Rockpool House in the heart of the beautiful West Highland Peninsulas of Sunart, Morvern, Moidart, Ardgour and Ardnamurchan. Categories

All

Archives |